What Is Modernism in Art? Movements, Ideas, and Global Impact

Modernism in art names a far-reaching transformation in visual culture that unfolded from the 1860s to the 1970s. Rather than a single style, it denotes an evolving constellation of movements that sought to rethink art’s purposes, methods, and meanings in light of modern life. Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Expressionism, Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism, Surrealism, and Abstract Expressionism—among others—signaled successive breaks with academic convention, realism, and narrative coherence. Modernist artists pursued new ways of seeing and making, privileging formal experimentation, abstraction, and a conscious engagement with the conditions of perception, experience, and materials. While originating largely in Europe and later flourishing in the United States, Modernism became a global force that was adapted and reinterpreted across diverse cultural contexts. This article surveys the context, ideas, stylistic innovations, key figures, techniques, and enduring legacy that define Modernism in art.

Historical Context

Modernism emerged against the backdrop of industrialization, urban growth, and rapid technological change in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Railways, factories, and new communication systems altered the tempo and texture of daily life, transforming cities and social relations. Many artists came to feel that inherited academic formulas and mimetic standards could no longer capture the intensities and fragmentations of modern experience. The desire to respond to these shifting realities helped drive a departure from established pictorial conventions and a search for new artistic languages.

Early institutional flashpoints reveal how Modernism crystallized from friction with dominant norms. In 1863, the Salon des Refusés in Paris presented works rejected by the official Salon and drew public attention to artists who questioned academic ideals. This episode has come to stand as a symbolic inception of Modernism’s challenge to official taste. A generation later, in 1913, the Armory Show in New York introduced European Modernism to American audiences, provoking shock and curiosity. Such exhibitions not only disseminated new ideas but also made visible the widening gap between academic authority and avant-garde practice, a gap that became a defining feature of the modernist era.

World War I intensified disillusionment with inherited ideals. The devastation and cultural upheaval of the conflict generated skepticism about stable truths and linear progress, conditions that fed into Modernism’s anti-traditional ethos and, in some cases, radical negations. Contemporary intellectual currents shaped the arts as well. Friedrich Nietzsche’s critique of morality and truth encouraged suspicion of absolute values, while Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis redirected attention inward, to unconscious drives and dream imagery. Such philosophical and psychological frameworks fostered experiments that lifted art away from descriptive fidelity and toward abstraction, symbolism, and surreal invention.

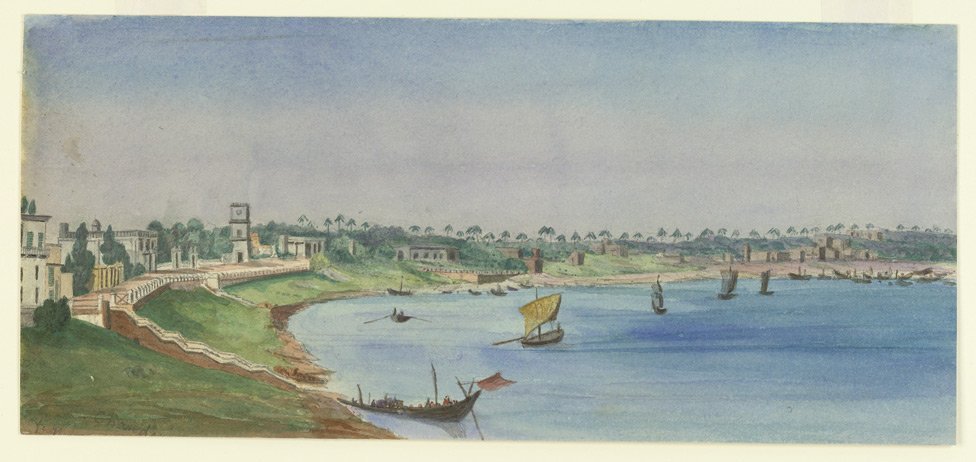

Modernism was never sealed within national boundaries. Colonial expansion and global cultural exchange brought non-Western forms and objects into European and American artistic circles, complicating Eurocentric art histories and stimulating new modes of seeing. These encounters became part of the matrix in which artists reimagined form and meaning, even as the dynamics of power and appropriation that framed such exchanges invite ongoing critical scrutiny. After World War II, geopolitical realignments and the migration of artists to the United States fostered a new center of gravity for artistic innovation. New York emerged as a leading site for experimentation, extending the modernist dialogue into fresh stylistic configurations while underscoring Modernism’s capacity to adapt to changed institutional and cultural environments.

Stylistic Characteristics

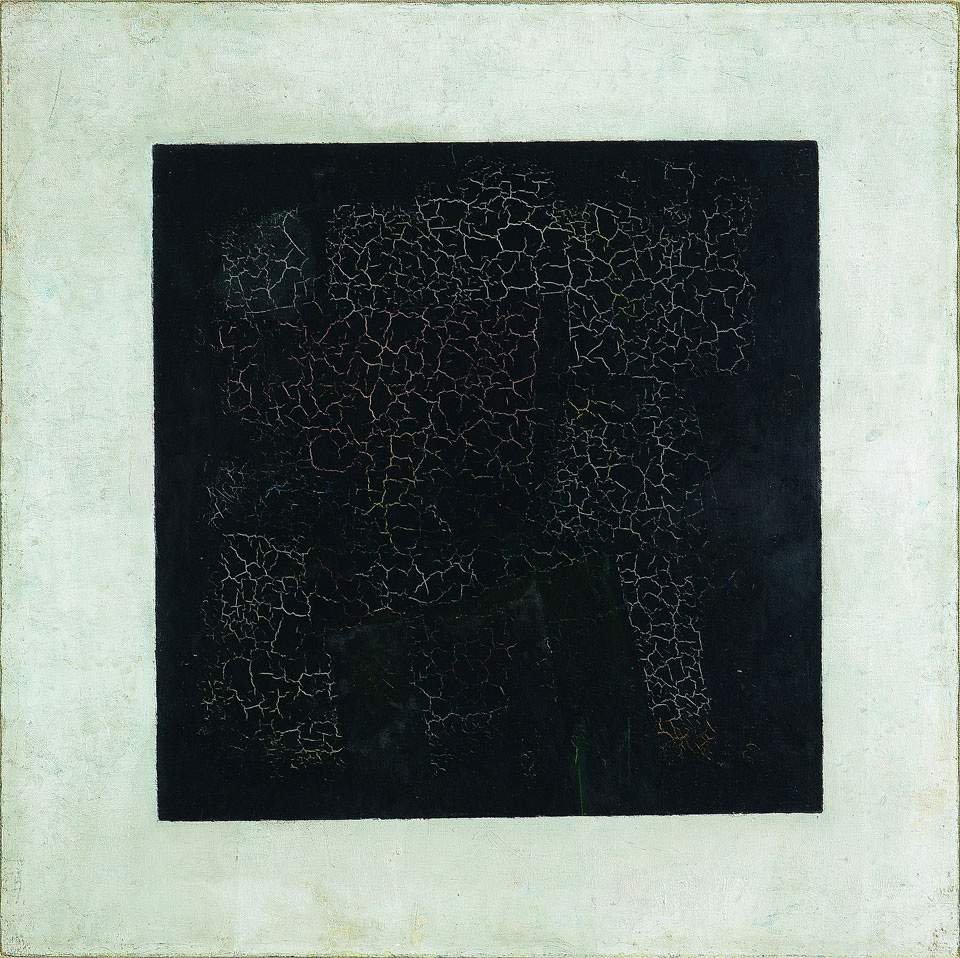

Modernism’s stylistic breadth masks a core of shared priorities. Foremost was a rejection of academic naturalism and of the belief that painting’s primary function was to reproduce the visible world or to narrate moralizing stories. In place of descriptive realism, modernist artists emphasized the autonomy of form—line, color, shape, and space—treating these elements not as tools for illusionistic representation but as subjects in their own right. The canvas or sculptural object became a site for exploring the conditions of vision and the presence of materials, often revealing the processes that produced the work.

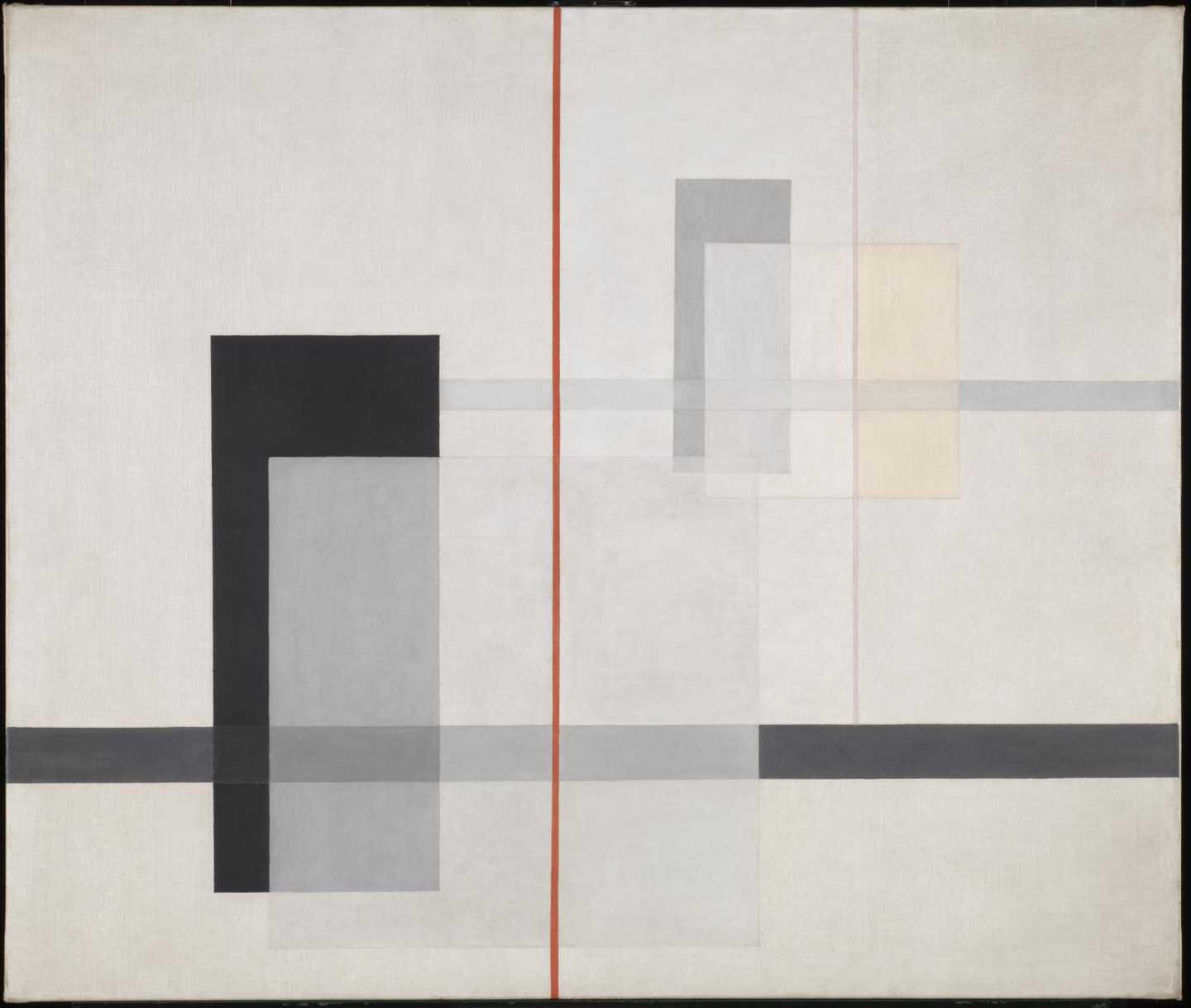

Abstraction became one of Modernism’s most potent strategies. In movements such as Cubism, forms were fragmented and re-assembled from multiple viewpoints, replacing single-point perspective with analytical structures that destabilized fixed ways of seeing. Fauvism and Expressionism pursued a different path, substituting bold, non-naturalistic color for naturalistic effects in order to articulate emotional and psychological intensities. Across these diverse practices, Modernism affirmed the artist’s subjective agency and encouraged formal innovation as a response to the complexities and rhythms of contemporary life.

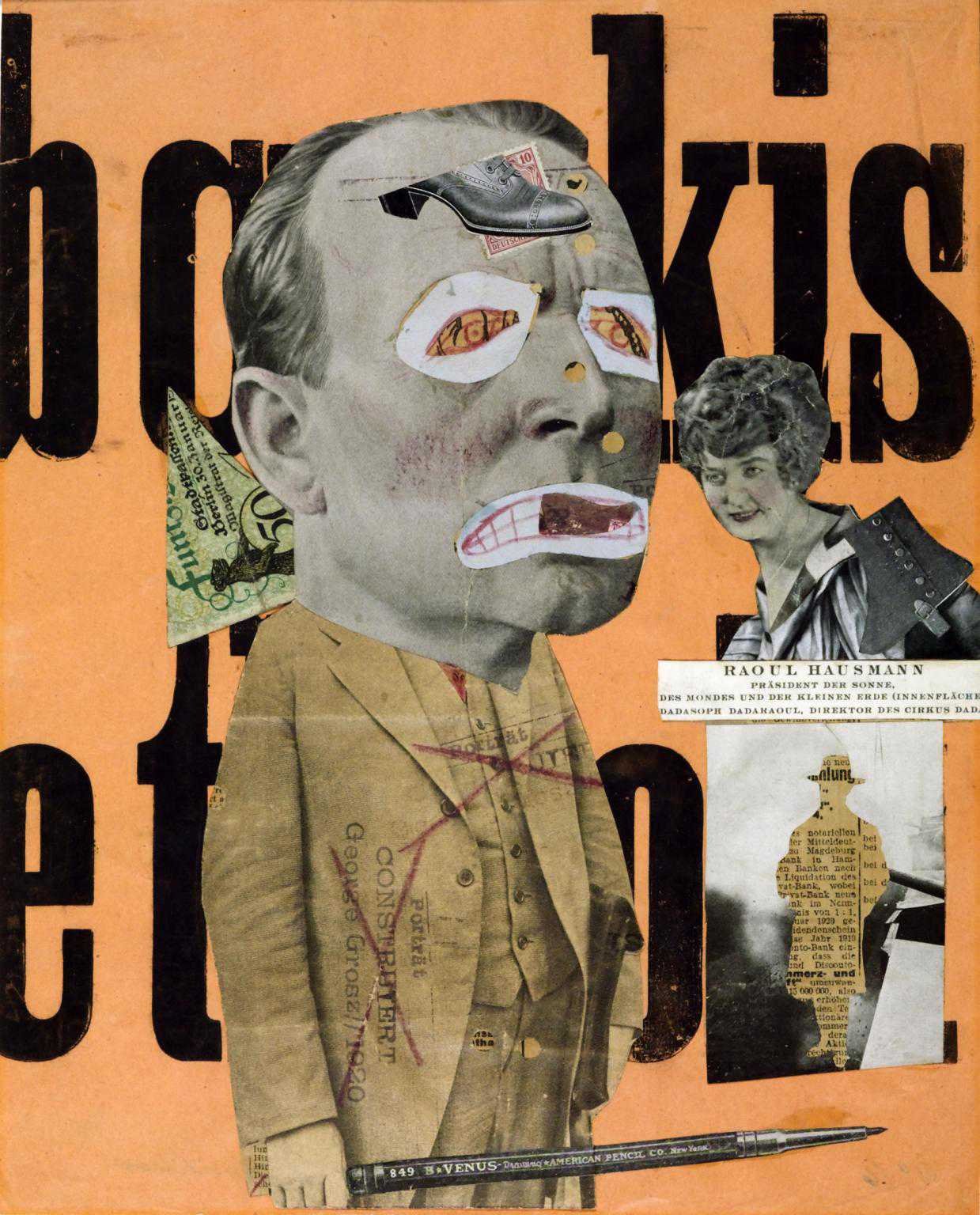

Modernists also cultivated reflexivity—a self-consciousness about the conventions and institutions of art. Some artists deployed irony, parody, and conceptual gambits to question what could count as art and why. The emphasis on the “truth” of materials and process made the physical qualities of paint, paper, or industrial substances visible, inviting viewers to consider how artworks are constructed rather than simply what they depict. This reflexivity intersected with experimentation in technique, from collage and mixed media to photomontage and the inclusion of found objects, extending the range of what an artwork might be made of and how it might operate.

Equally important was Modernism’s openness to ambiguity and viewer participation. Many modernist works resist definitive interpretation, shifting meaning as contexts and audiences change. Artists turned to new technologies—photography, film, and later video and digital tools—not merely as illustration of modernity but as engines for new aesthetics. Whether through austere geometry, gestural intensity, or dreamlike fantasia, Modernism persistently reimagined art’s role and possibilities in the modern age.

Key Artists & Works

Several signal works chart the trajectory of Modernism’s major movements and ideas. Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872) is often cited as a foundational statement for Impressionism, attending to shifting light and atmosphere rather than detailed topography. With loose brushwork and an emphasis on optical effects, Monet registered the fleeting conditions of perception in an urban-industrial harbor setting, setting a precedent for later artists who would privilege sensation and immediacy over finished academic finish.

Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889) advanced Post-Impressionism’s interest in subjective expression and structural experimentation. Its swirling brushwork and charged color convey emotional intensity, underscoring how surface handling and chromatic contrasts could become agents of meaning beyond direct description. Post-Impressionist experiments also informed the development of more radical departures from mimesis, as artists explored the expressive power of line, color, and composition.

Henri Matisse’s The Dance (1910) embodies Fauvism’s embrace of vivid color and rhythmic compositional schemes. By simplifying forms and intensifying color contrasts, Matisse reconfigured the relationship between figure, ground, and pictorial space, suggesting that painting’s substance is not the recollection of appearances but the orchestration of chromatic and spatial energies. Fauvism’s approach resonated across modernist practices in which color was a vehicle for feeling rather than a transcription of the visible world.

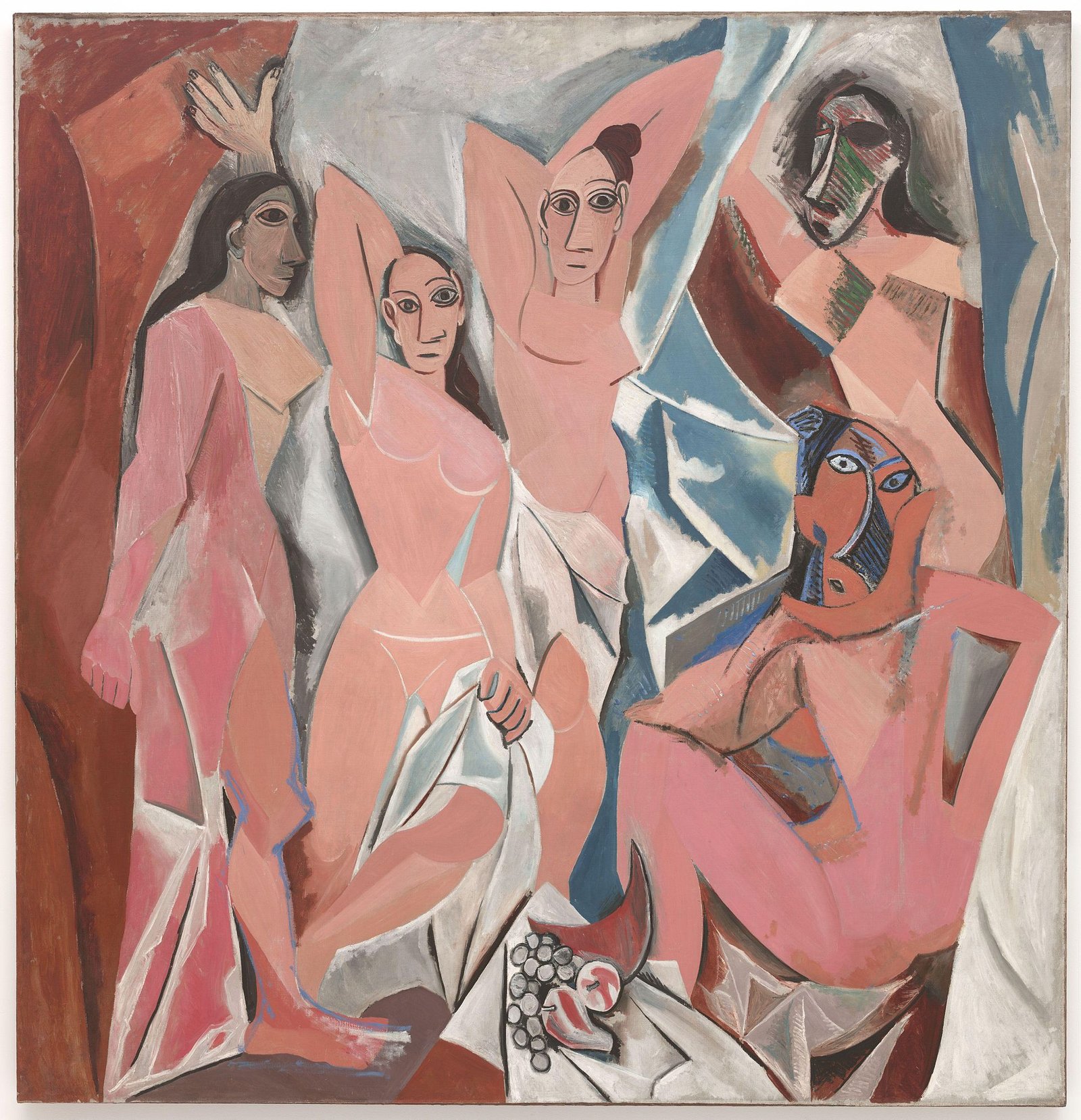

Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) stands as a seminal work associated with the emergence of Cubism. It rejects conventional perspective in favor of fractured planes and multiple viewpoints, signaling a fundamental reconsideration of how space, form, and the human figure can be represented. In parallel, Georges Braque’s Violin and Candlestick (c. 1910–12) exemplifies Analytical Cubism’s intricate constructions, in which objects are dissected into interlocking facets that propose an active, temporal experience of looking rather than a static, singular view.

In Italy, Umberto Boccioni’s Dinamismo di un Ciclista (1913) reflects Futurism’s fascination with speed, movement, and the dynamism of modern urban life. Through overlapping lines and accelerated rhythms, the work conveys motion as an essential content of art, aligning modern aesthetics with the mechanized tempo of the early twentieth century. Expressionism charted a distinct route toward interiority and psychological charge, seen in Egon Schiele’s Cardinal and Nun (1912), where distortion of form animates an intense, unsettling atmosphere.

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) crystallizes Dada’s challenge to the very definition of art. By presenting a readymade object in an art context, Duchamp foregrounded choice, context, and concept over traditional craftsmanship, expanding the modernist field to include the idea as artwork. Surrealism’s investigations of dream and the unconscious find a lucid emblem in Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931), where improbable juxtapositions and fluid time suggest a pictorial logic liberated from waking rationality.

Abstract Expressionism emerged later, with works such as Mark Rothko’s Orange, Red and Red (1962) foregrounding expansive fields of color that invite contemplative, affective engagement. Rather than depicting identifiable scenes, such paintings propose that color relationships themselves can carry emotional and spiritual weight. Frida Kahlo’s autobiographical paintings, which blend Surrealism and symbolism, likewise underscore the modernist drive to connect personal narrative and inner life with new pictorial idioms.

Other widely cited figures within the modernist arc include Paul Cézanne, whose investigations of structure and perception informed later abstraction; Paul Gauguin, who sought alternative modes of representation as a counter to naturalism; Wassily Kandinsky, associated with pioneering efforts in abstraction; Piet Mondrian, who pursued geometric order; Joan Miró, who cultivated hybrid vocabularies of sign and dream; and Jackson Pollock, known for an approach to painting that emphasized process and gesture. Together, these artists illustrate the range and restless evolution of Modernism, which unfolded through overlapping experimentations rather than a linear sequence of styles.

Materials & Techniques

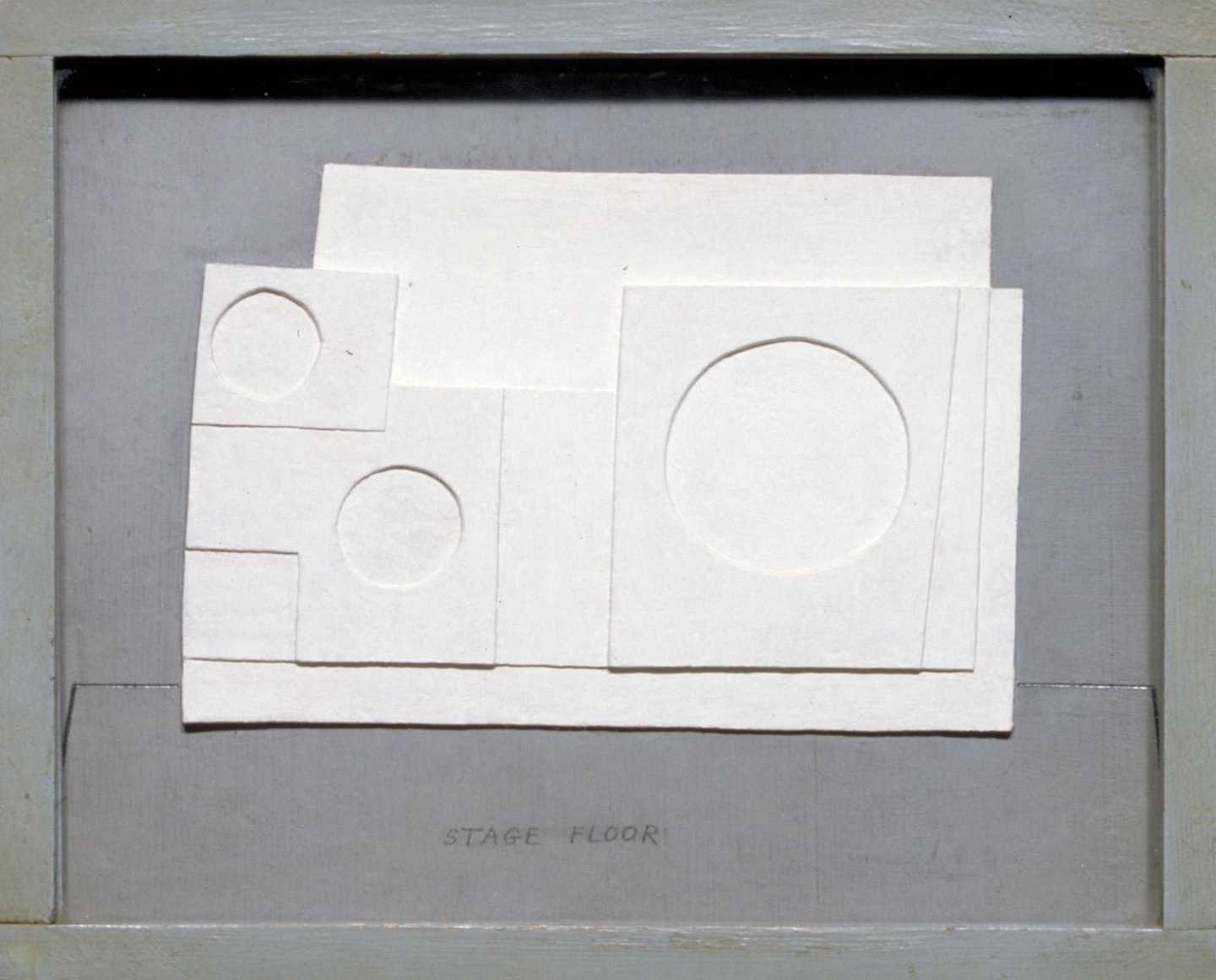

Modernism reimagined what artists could do with traditional mediums even as it expanded the repertoire of materials and processes. Oil on canvas and conventional sculpture remained staples, but they were used in ways that emphasized surface, facture, and the autonomy of form. A visible, at times audacious brushstroke signaled a move away from illusionistic depth toward an emphasis on painting’s flatness, pigment density, and texture. The physical presence of the medium—its drag, thickness, and translucency—became a subject in itself, reinforcing the notion of material truth.

![What Is Modernism in Art? Movements, Ideas, and Global Impact 6 Pablo Picasso Mère et enfant [Mother and Child] 1902 © Succession Picasso. DACS, London 2023](https://cogindia.art/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Pablo-Picasso-Mere-et-enfant-Mother-and-Child-1902-©-Succession-Picasso.-DACS-London-2023.jpg)

Collage fundamentally altered the modernist toolkit. By incorporating printed papers, photographs, and ephemera into compositions, artists collapsed distinctions between “high” art and the detritus of everyday life. Photomontage and assemblage extended this logic, combining disparate fragments and found objects into new wholes. Dada and Synthetic Cubism made these practices central, foregrounding the idea that meaning could arise from juxtaposition and context as much as from artisanal transformation. Found objects, including industrial and everyday materials, challenged assumptions about artistic labor and aura while aligning art with the textures of modern experience.

New technologies fostered new aesthetics. Photography’s capacity to fix fleeting moments and to frame reality from novel vantage points inspired experiments in perspective, cropping, and montage. Film and, later, video introduced time, movement, and seriality into artistic thinking, while performance and installation expanded the artwork beyond static objects into spatial and experiential domains. Digital media eventually entered the field, extending modernist commitments to innovation and experimentation into the computational age.

Techniques varied widely among modernist movements. Automatic drawing, cultivated within Surrealism, aimed to bypass rational control and channel the unconscious, aligning process with psychological theory. Gestural painting, a hallmark within Abstract Expressionism, emphasized the act of painting as a record of movement and decision, fusing process with visual outcome. Geometric abstraction, associated with projects such as De Stijl, sought order and clarity through reduced forms and calibrated relationships, proposing that balance and harmony could emerge from rigorous formal limits. Across these diverse approaches, the artistic process itself—whether improvisatory, systematic, or conceptual—became a crucial site of meaning.

Influence & Legacy

Modernism fundamentally reshaped Western art by breaking with centuries of representational conventions and proposing that artistic value could reside in form, concept, and process rather than in mimicry or narrative. These transformations opened paths to abstraction and conceptual art, reframing what counted as a legitimate artwork and what artists might ask of their audiences. The modernist emphasis on innovation and individual expression fostered an ecology in which new movements could emerge rapidly, each challenging or reinterpreting the last.

The movement’s impact extended well beyond the visual arts. In architecture, the modernist spirit informed the Bauhaus and related developments tied to the International Style, aligning design with industrial production and functional clarity. Modernist ideas affected music through atonality and twelve-tone technique, reconfiguring harmonic expectations, while modern dance explored the body’s weight, gravity, and expressive range outside classical ballet’s codified steps. Literature embraced stream of consciousness to mirror the intricacies of thought and perception, and philosophical debates about truth, representation, and subjectivity paralleled the visual arts’ questioning of stable meanings. These cross-disciplinary resonances attest to Modernism’s capacious rethinking of form and experience across culture.

Institutions played a decisive role in consolidating, contesting, and disseminating modernist art. The Armory Show and the Salon des Refusés served as early catalysts that displayed alternatives to academic orthodoxy. Throughout the twentieth century, museums and collections codified Modernism’s canons while also challenging them. The Museum of Modern Art in New York, Tate Modern in London, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the National Galleries of Scotland have been central to presenting and interpreting modernist works for broad audiences. Such institutions have also contributed to the ongoing debate over how Modernism should be periodized and narrated, especially as new research foregrounds previously marginalized histories and contexts.

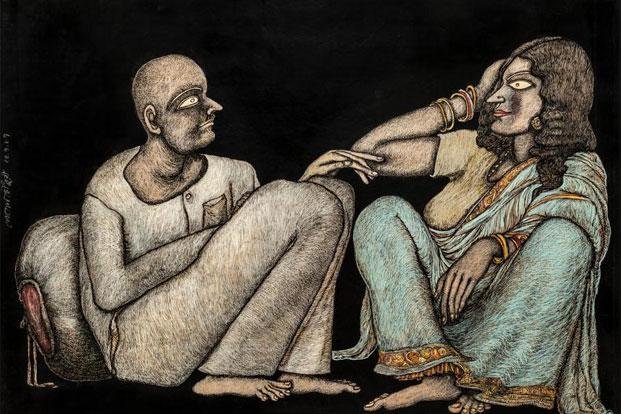

Modernism’s global reach is a defining part of its legacy. As ideas traveled, they were adapted to diverse cultural conditions and debates, generating distinctive articulations such as Indian Modernism and Japanese Modernism. These developments emerged within complex colonial and cultural power dynamics that shaped what was visible, who was included, and how influence was attributed. Exhibitions such as “Triumph of Modernism: Indian Artists and Global Modernism, 1922–1947” underscore the importance of expanding the narrative to account for non-Western modernist practices and their dialogues with international currents. This reflexive re-mapping of Modernism does not erase its European and American origins; rather, it demonstrates how modernist ideas were translated, contested, and renewed across different places and times.

After World War II, the migration of artists and the ascendancy of New York as an art capital underscored Modernism’s adaptability to changing political and cultural landscapes. Subsequent developments commonly identified as contemporary art and postmodernism built on modernist innovations, even when they critiqued them. Strategies such as appropriation, institutional critique, and multimedia installation found precedents in modernist experimentation with materials, form, and concept. In the present, Modernism’s legacy persists in digital art, performance, and immersive installations, where artists continue to test the limits of medium, authorship, and audience engagement in ways that echo and extend modernist concerns.

At the same time, certain questions remain under active scholarly discussion. The precise timelines of Modernism, Late Modernism, and Postmodernism are debated, as are the criteria by which particular works or movements are classified. The extent and nature of non-Western influences and the ethics of cultural borrowing require ongoing, nuanced research. Regional receptions, institutionalization processes, and archival recoveries continue to refine our understanding of how Modernism operated in different contexts. These debates are not peripheral to the movement’s legacy; they are intrinsic to an art historical field shaped by Modernism’s own commitment to questioning assumptions and revising frameworks.

Conclusion

Modernism in art names a pivotal reorientation of aesthetic priorities, one driven by the challenges and possibilities of modern life. From Impressionism’s attention to perception to Abstract Expressionism’s emphasis on process and affect, modernist movements collectively redefined what art could be and how it could mean. They rejected academic realism and narrative formulae, affirmed the autonomy of form, and invited viewers to encounter artworks as arenas of experiment, ambiguity, and reflection. These transformations unfolded in relation to industrialization, war, and intellectual debates about truth and the unconscious, while also being shaped by global cultural exchanges that complicate any strictly Euro-American account.

Through innovations in materials and techniques—collage, assemblage, readymade objects, automatic methods, gestural strategies, geometric abstraction—and through engagements with photography, film, and later digital media, Modernism expanded the boundaries of artistic practice. Its influence reverberates across architecture, music, dance, literature, and philosophy, while its institutional history, from landmark exhibitions to the formation of major museum collections, has framed how we perceive and evaluate modernist art today. If the period’s start and end points remain fluid and some categorizations are contested, such uncertainty aligns with Modernism’s own ethos: a sustained willingness to revise premises, test limits, and pursue new forms adequate to changing realities. For scholars, artists, and audiences, Modernism endures not as a finished chapter but as an evolving resource—a set of ideas and practices that continue to inform how art engages the world.