Sacred Geometry in Indian Temple Design: Cosmology, Proportion, and Architectural Practice

Across the Indian subcontinent, Hindu temples articulate a compelling union of sacred geometry, ritual function, and cultural memory. These structures are more than places of worship; they are cosmographic diagrams rendered in stone and brick, conceived as abodes of the divine and as microcosms of the universe. Their plans and elevations are orchestrated through canonical measurements and grids that translate philosophical concepts into built form. The result is a continuum of regional styles and centuries of innovation—yet underpinned by a shared geometric grammar that ties the sanctum, halls, superstructures, and sculptural programs into a coherent whole. Examining sacred geometry in Indian temple design thus reveals not only how space is ordered and embellished, but how that order communicates Hindu cosmology, supports ritual practice, and sustains communal life. This article surveys the historical development, architectural logic, iconography, inscriptions, and cultural functions of temple geometry, drawing on key examples and textual traditions to outline a clear, evergreen understanding of the subject.

Historical Background

Indian temple architecture did not appear fully formed. It evolved over long periods, tracing a trajectory from early ritual altars and rock-cut sanctuaries to mature, structurally complex edifices. In its prehistory, the formalization of sacred space drew from early Vedic altar constructions, where ritual geometry organized sacrificial precincts, and from the rock-cut traditions that shaped Buddhist cave temples. By the Mauryan period in the 3rd century BCE, the subcontinent’s architectural vocabulary was expanding, establishing a foundation for the spatial refinements that would emerge in later centuries.

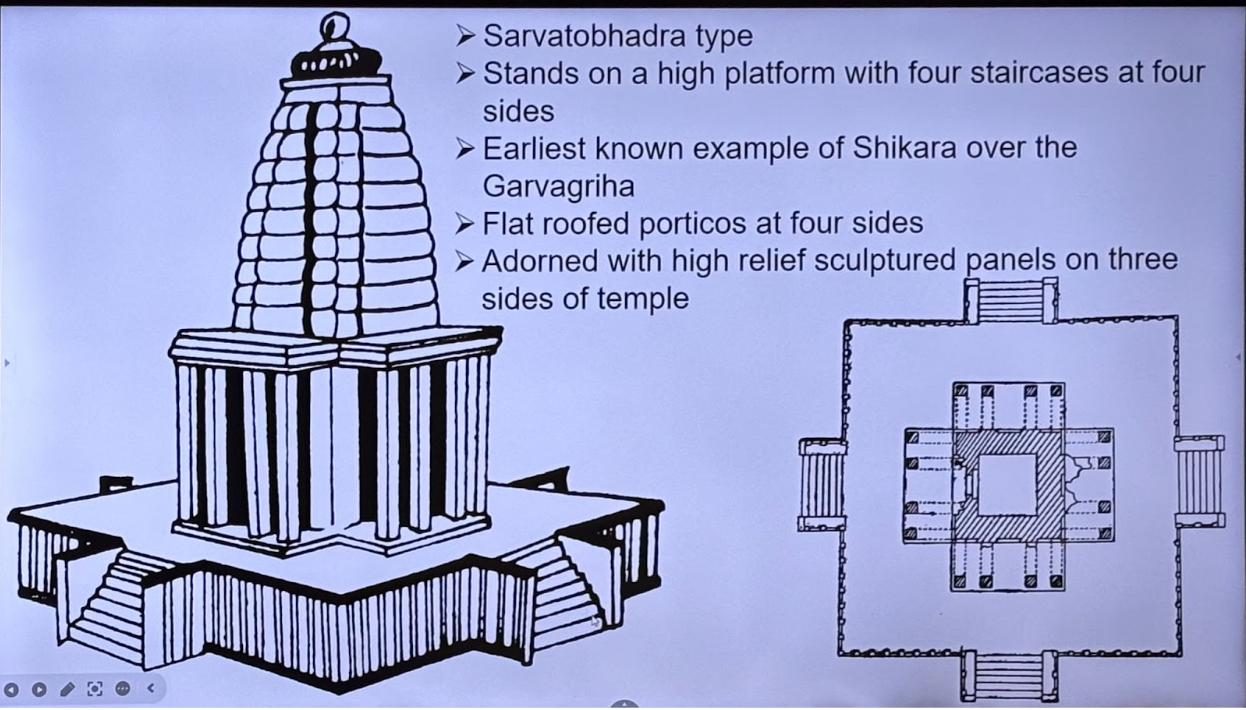

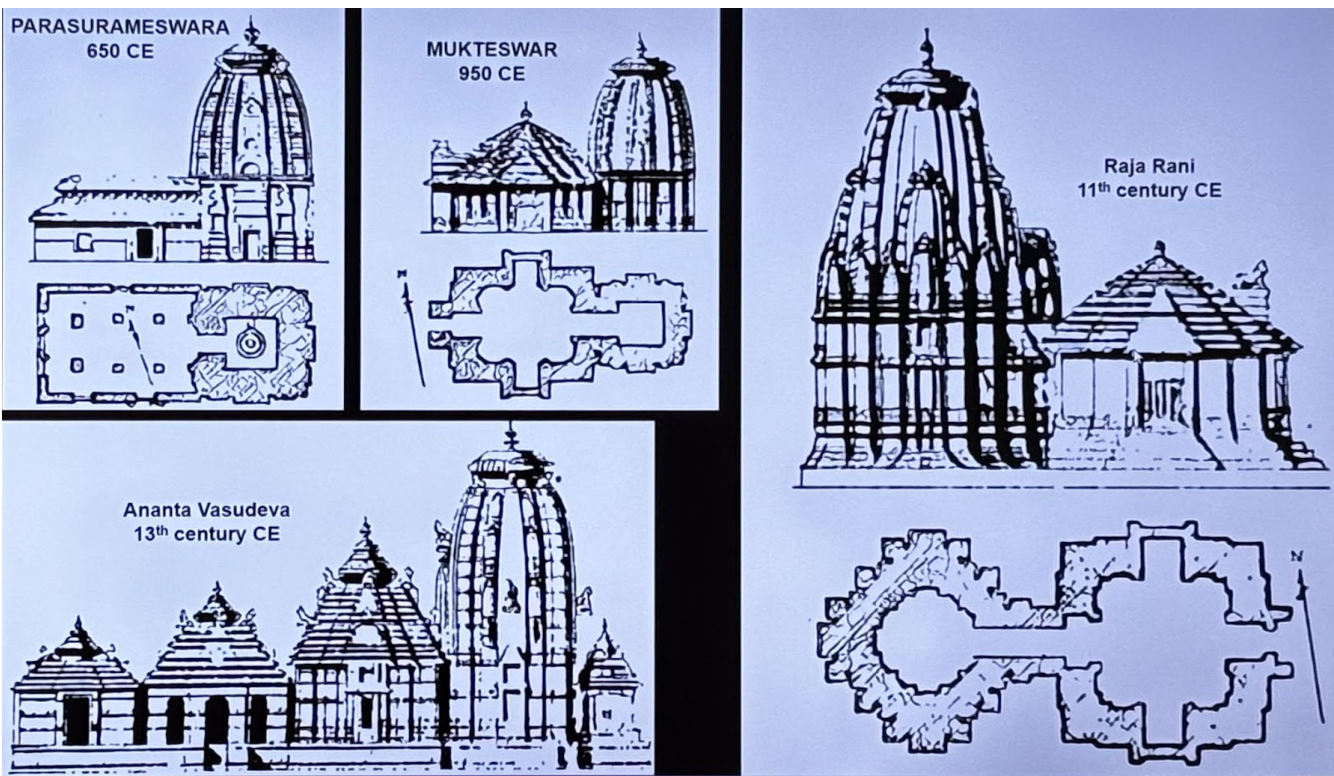

The Gupta period, from the 4th to the 6th century CE, represents a decisive stage in this evolution. Experimental and exploratory, it witnessed the transformation from simple, often open-air or rock-cut sanctuaries into structural stone temples. Typologies were articulated in terms such as Sandhara, Nirandhara, and Sarvatobhadra, reflecting concerns with circumambulatory paths, accessibility, and the sanctity of the core chamber. The Gupta era’s investigations into form, proportion, and typology laid the groundwork for subsequent regional elaborations, establishing the importance of precise modularity and the square sanctum as a generative geometric unit.

Medieval dynasties built upon these foundations, developing complex stylistic lineages. Chalukyas, Pallavas, Cholas, Rashtrakutas, Hoysalas, Solankis, and Chandellas each refined and localized architectural conventions. Their collective achievements ranged from grand complexes to intricately articulated shrines, calibrated to both sacred texts and material craft. The Vijayanagara Empire in the 14th to 16th centuries further consolidated and disseminated these practices, advancing monumental gateways and expansive temple-cities that integrated urban, ceremonial, and sacred spheres. Across this expansive history, geometry was a constant: a framework through which builders aligned spaces to cosmological ideas while responding to regional materials, climate, and courtly patronage.

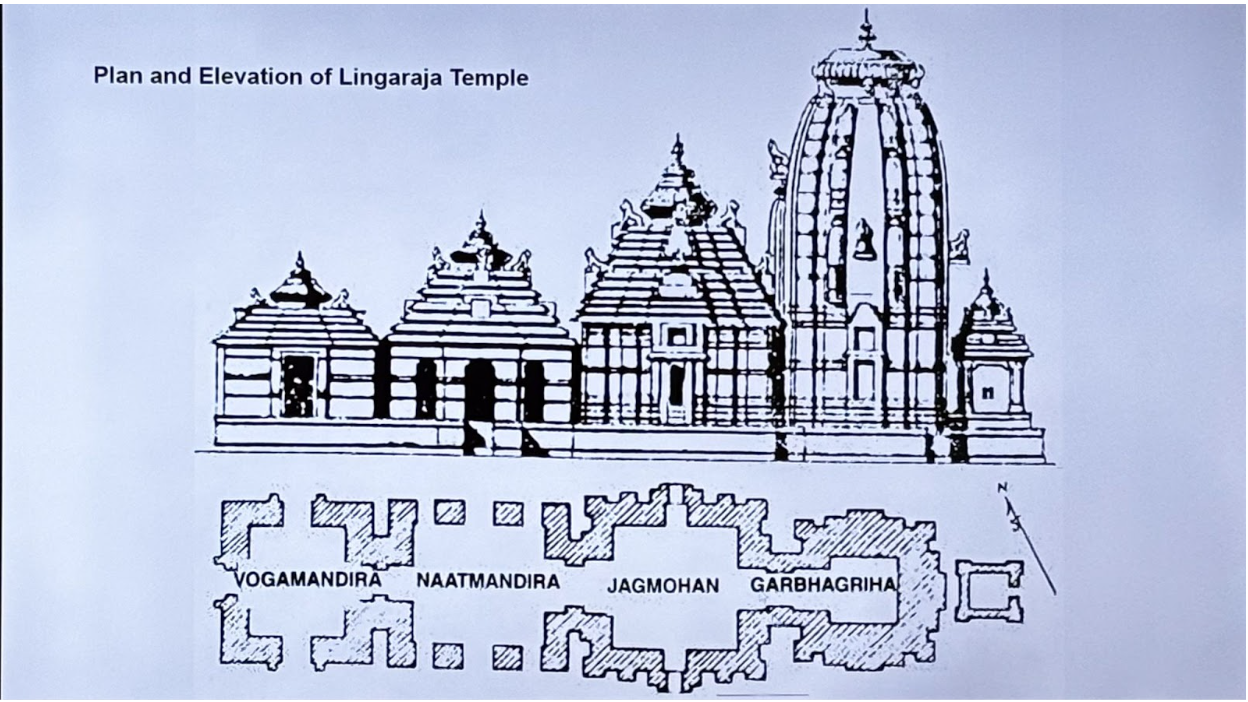

This evolution is visible in canonical examples and archaeological sites. Temples such as Lingaraj in Odisha, Brihadeshwara in Tamil Nadu, Kandariya Mahadev at Khajuraho, the monolithic Kailasa at Ellora, and the Madurai complex of Minakshi Sundareswara collectively demonstrate the regional diversity of form, coupled with fidelity to sacred planning and proportional systems. Sites like Deogarh, Sanchi, Ellora, Mahabalipuram, Khajuraho, and Bhubaneswar preserve physical evidence of how typologies, geometry, and superstructures unfolded in practice. Inscriptions across many temples record patronage, construction, and rituals, reinforcing the historical continuity of sacred architectural knowledge and the technical precision that undergirds it.

Architecture & Layout

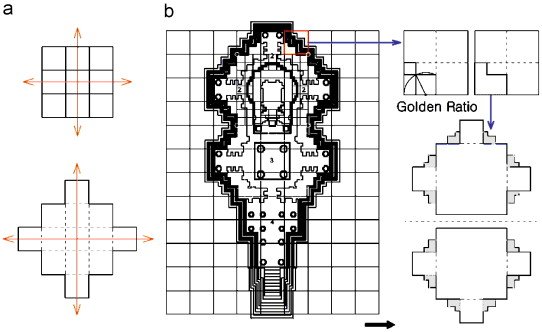

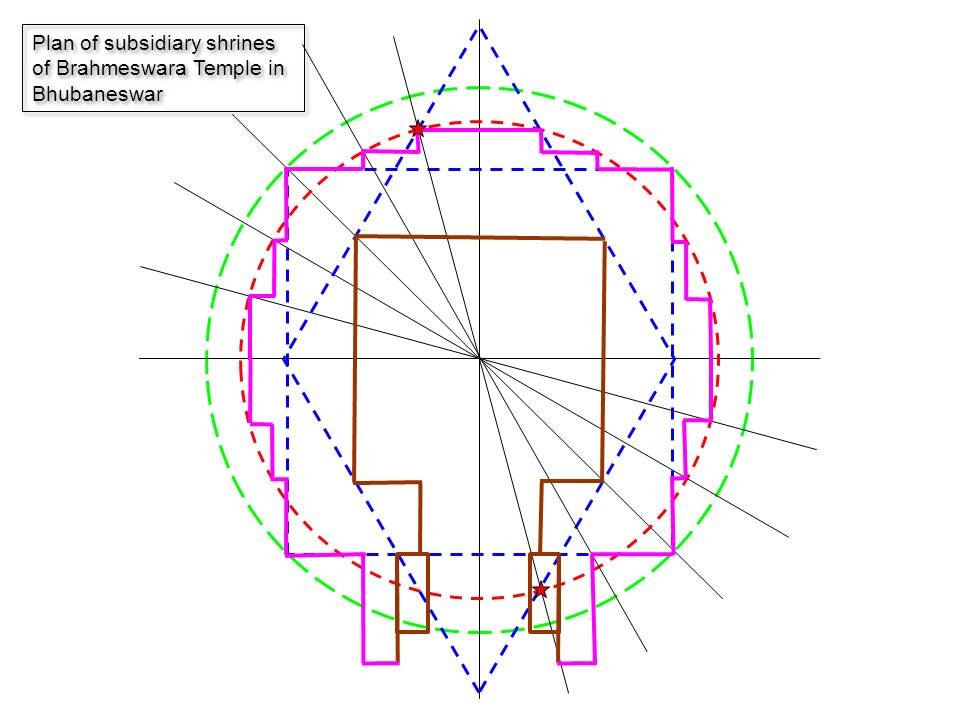

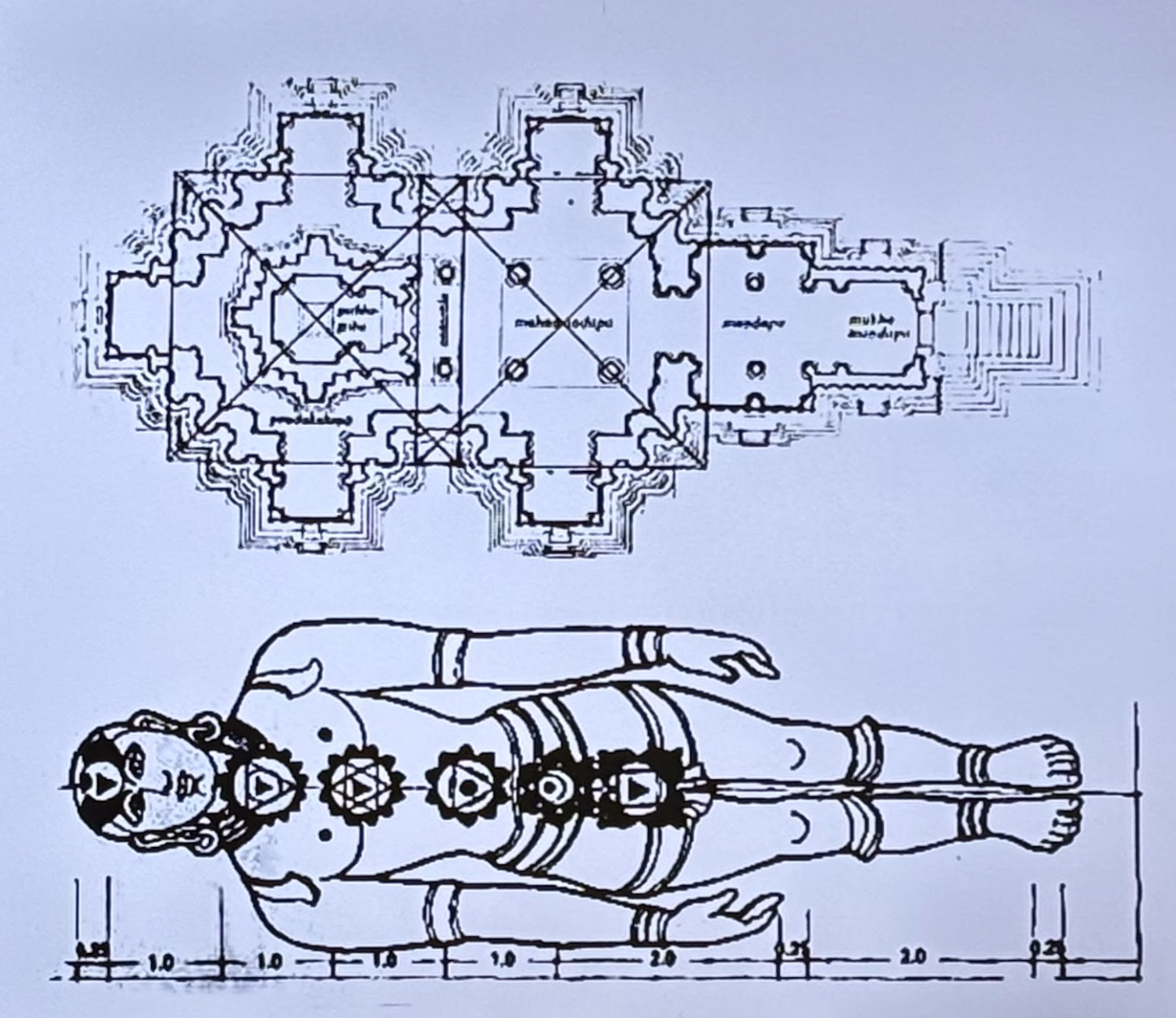

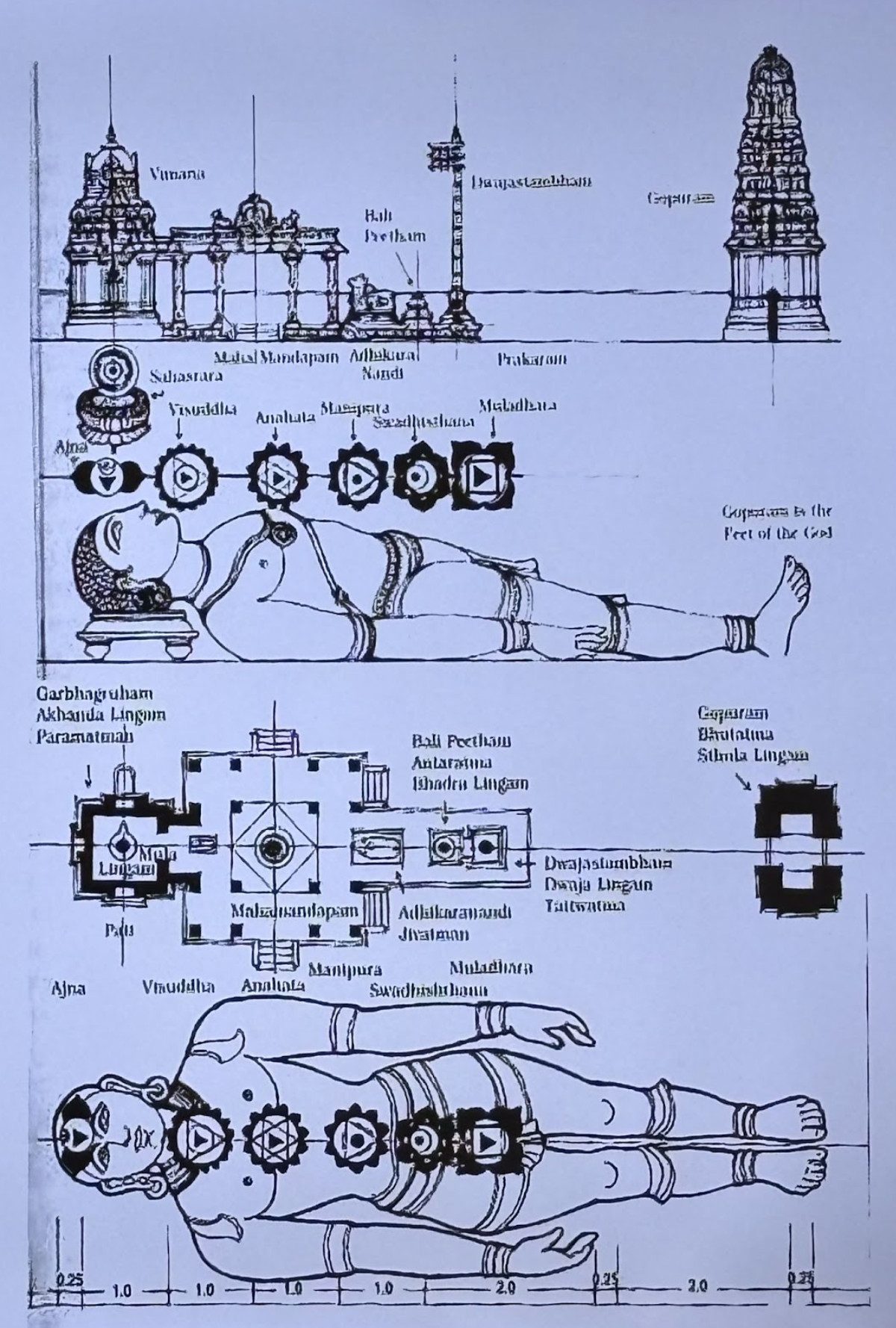

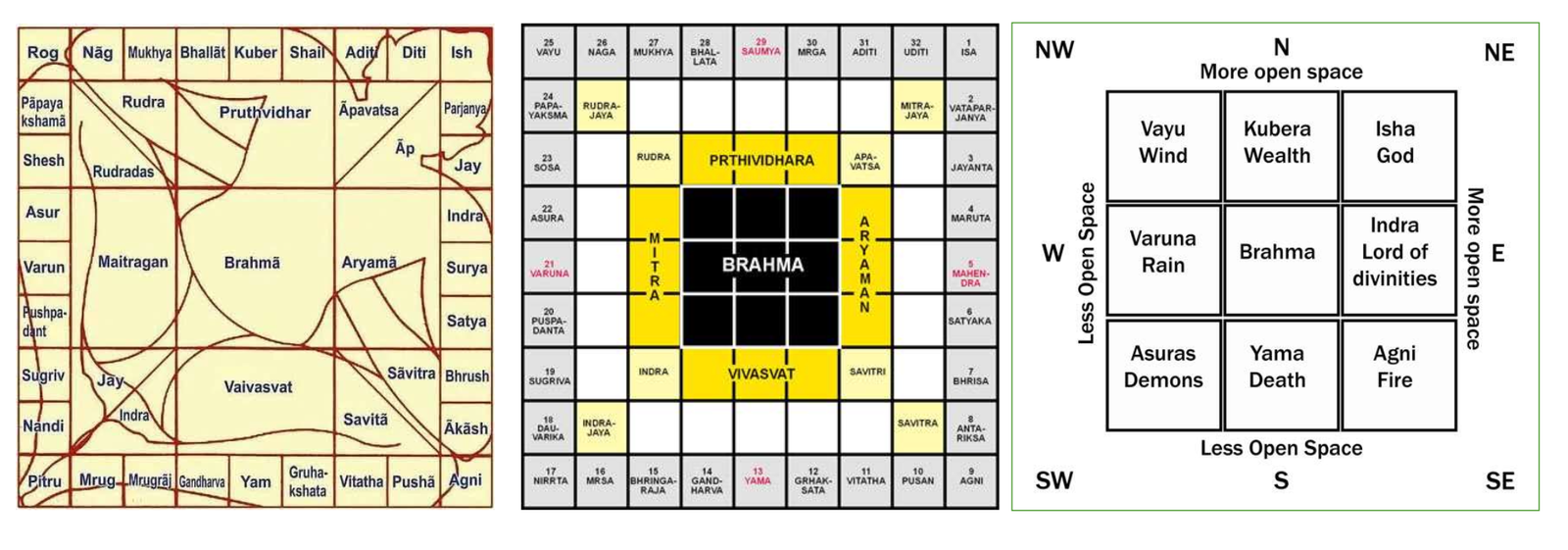

The generative basis of Indian temple design is the Vastupurusha Mandala, a diagrammatic grid that represents both cosmic order and the body of Purusha, the primordial cosmic being. This mandala serves as a master plan, allocating zones and axes that regulate orientation, entrance, circulation, and the hierarchy of spaces. Its square logic aligns the temple with cardinal directions and ordains the disposition of the sanctum, mandapas, and subsidiary structures. Through this matrix, metaphysical concepts are given architectural clarity: the temple becomes a measured cosmos in which the sacred core is framed by progressively accessible spaces.

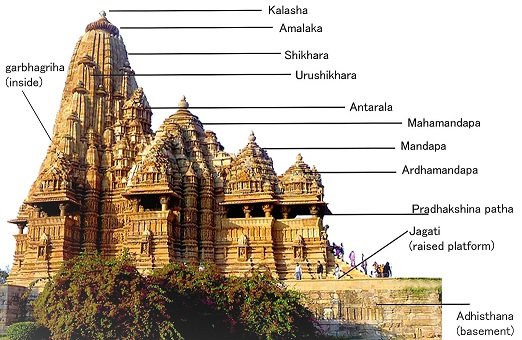

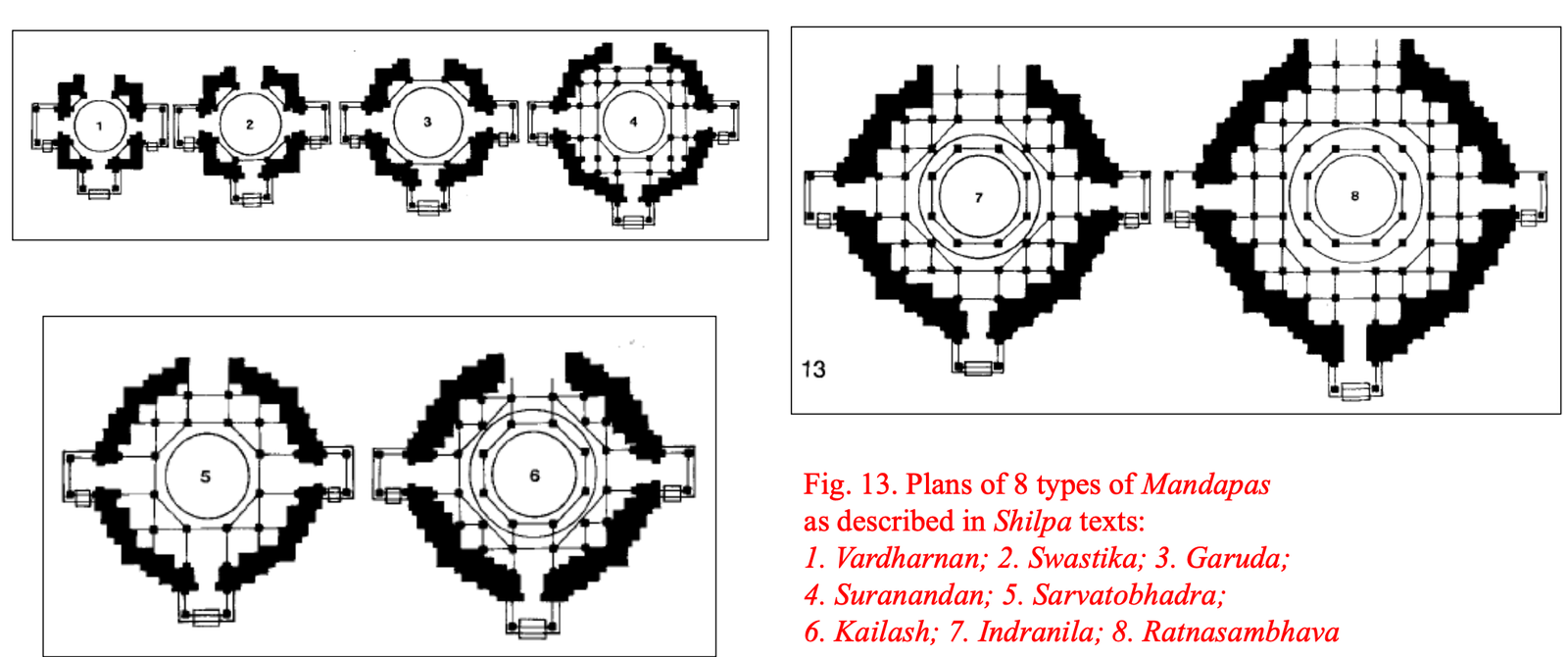

At the heart of the plan is the garbhagriha, the sanctum or womb-chamber, usually square or rectangular and intentionally enclosed. Around this nucleus unfold one or more mandapas, pillared halls that accommodate liturgy, congregational presence, and the processional movements that are integral to ritual practice. Many temples incorporate a pradakshina patha—an ambulatory for circumambulation—either enclosed around the sanctum or articulated as a clear path within the temple complex. This pattern of nested, axial, and processional spaces expresses a deliberate choreographing of movement, aligning embodied practices with the temple’s cosmographic structure.

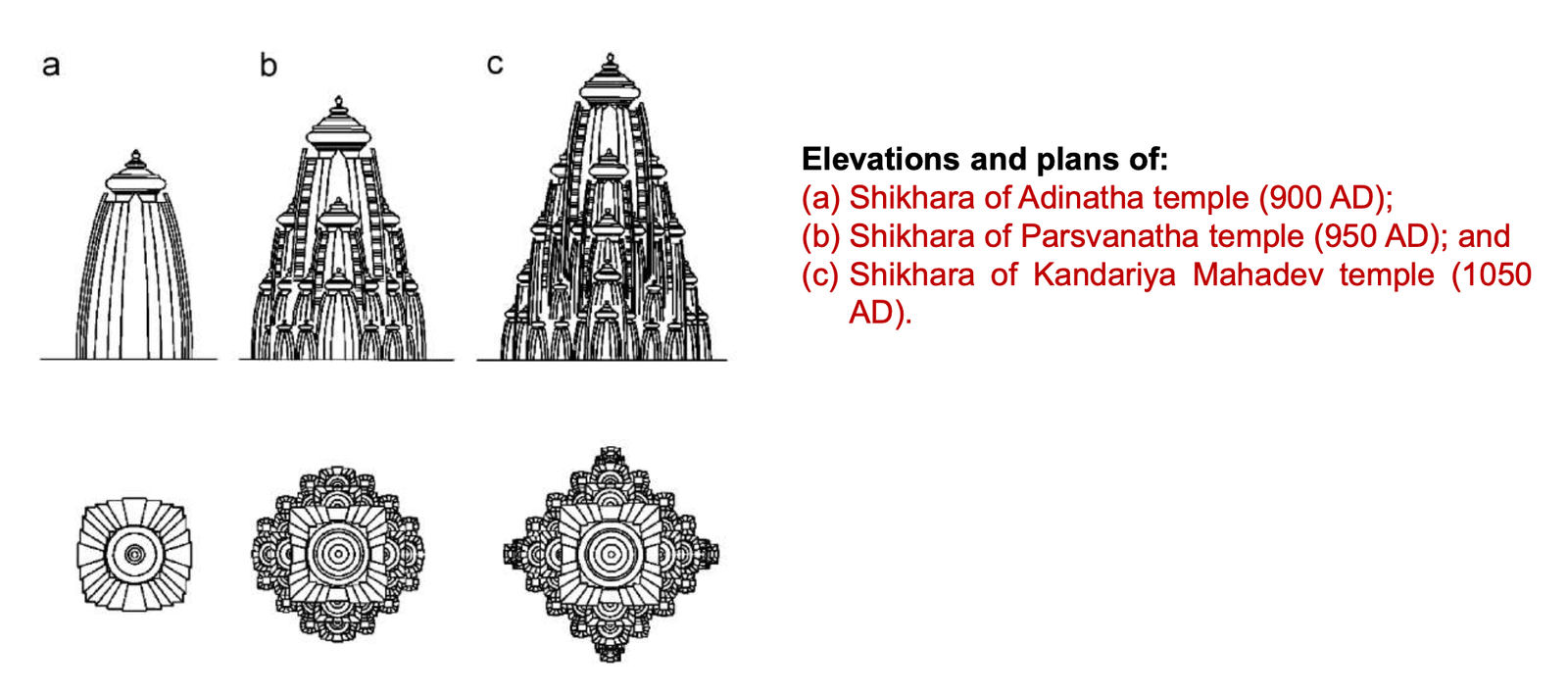

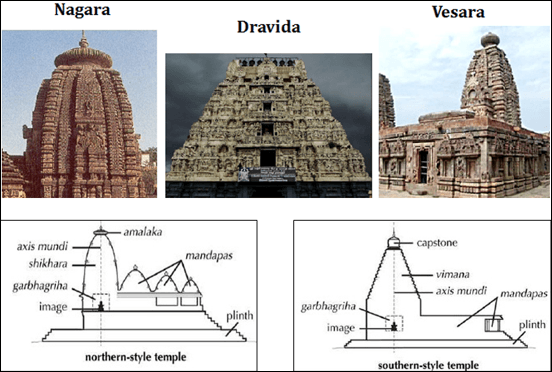

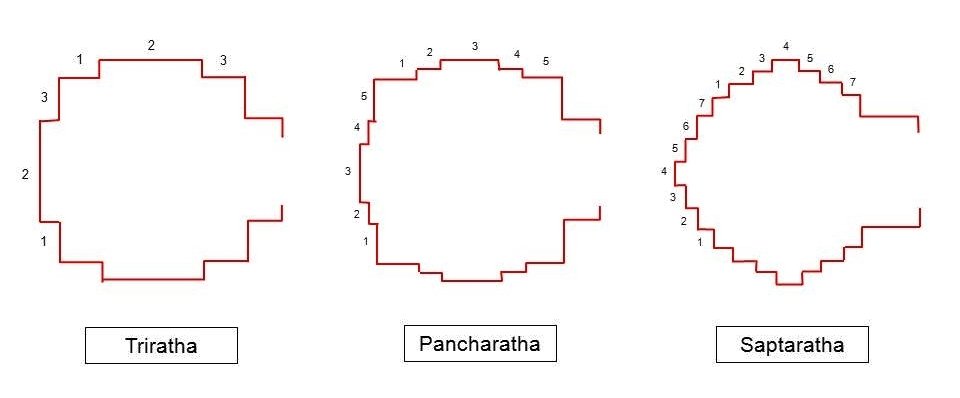

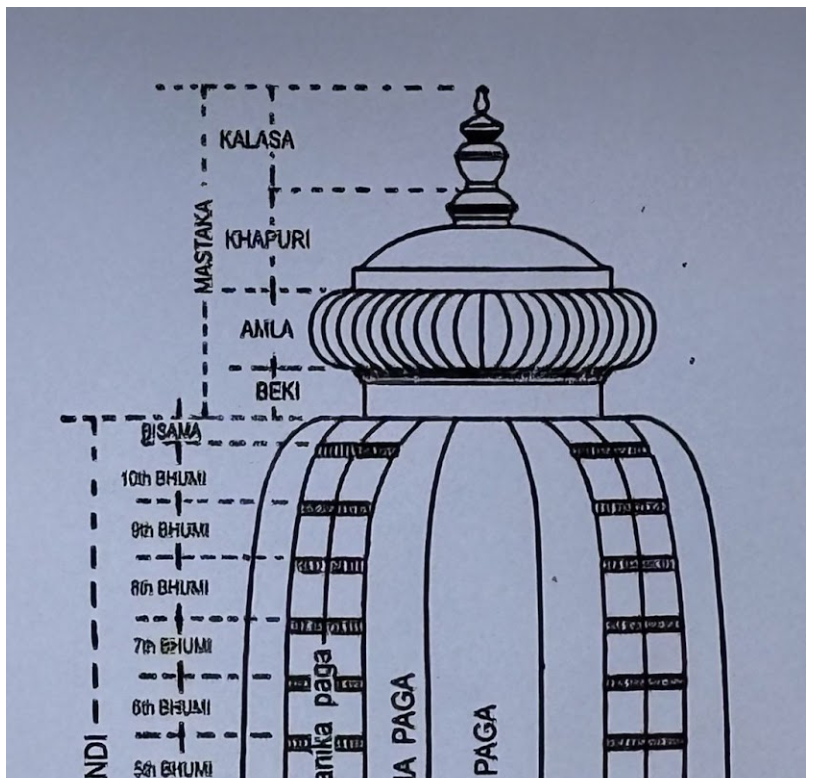

The superstructure over the sanctum assumes regionally distinct forms. In the Nagara style of North India, the shikhara rises with a curvilinear profile, often articulated by projections (rathas) and crowned by symbolic elements such as discs that accent the vertical climax of the structure. In the Dravida style of South India, the tower or vimana is pyramidal, built in tiered storeys that recede rhythmically. Gateways in this tradition, known as gopurams, may become monumental in their own right, shaping the visual identity of the complex. The Vesara style blends aspects of both Nagara and Dravida idioms, reflecting geographic and cultural exchange in the Deccan. In Odisha’s Kalinga style, spatial composition is parsed into distinct building forms: the Rekha Deula (the soaring tower of the sanctum), Pidha Deula (pyramidal-roofed halls), and Khakhara Deula (with characteristic apsidal or pumpkin-shaped roofs), together expressing a coherent progression of volumes around the sacred core.

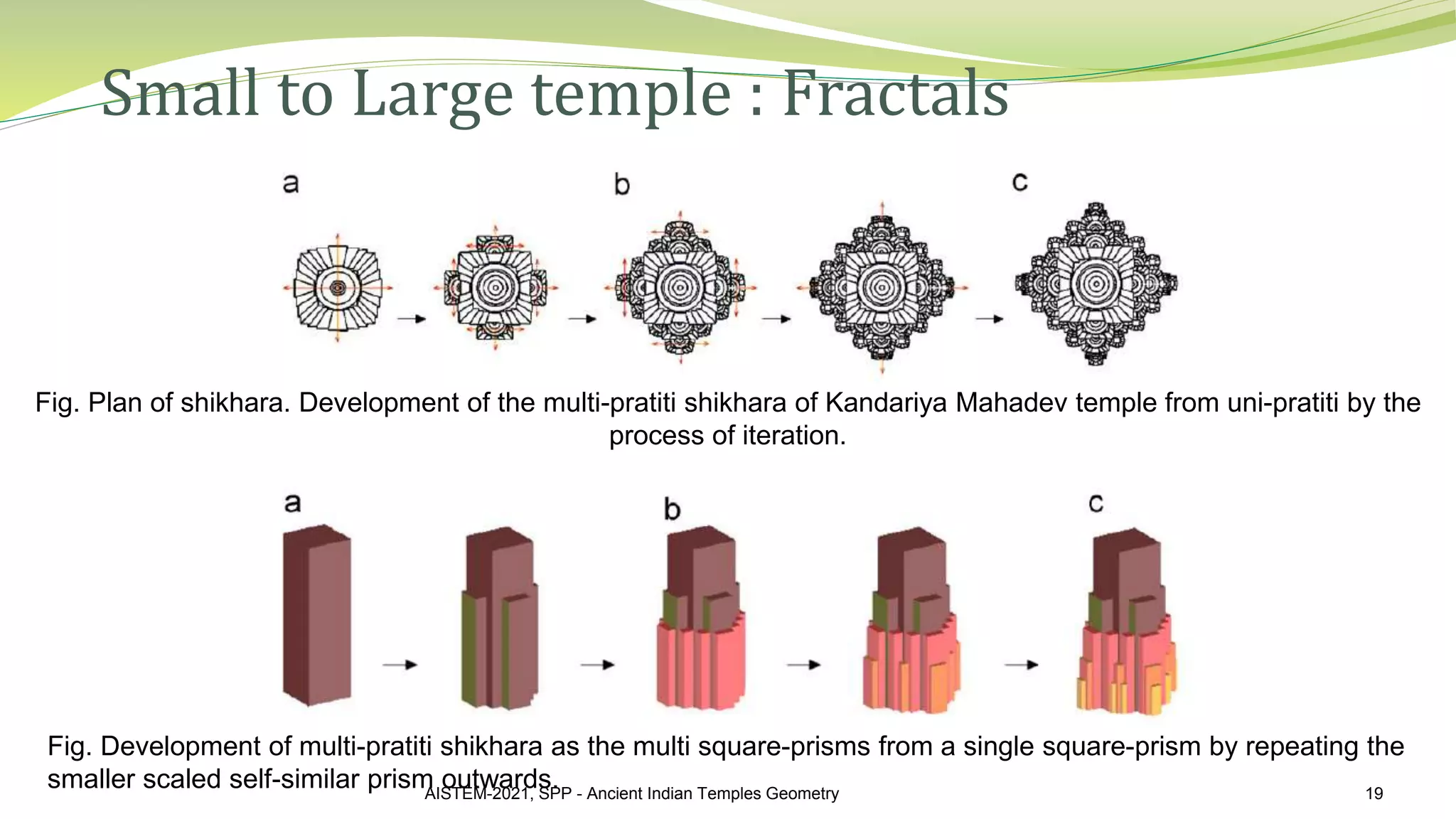

Temples typically rise on a raised platform or jagati, setting the sacred space apart from quotidian ground and establishing a clear base for the ascending architectural mass. This base often exhibits multiple mouldings and articulated zones—pitha, vedibandha, jangha, and varandika—that frame the shift from the earthly plinth to the sanctified vertical stack. These layers mediate between human scale and monumental form, while also reinforcing the compositional clarity of the temple’s elevation. Structural features frequently display fractal-like qualities: self-similar projections, recesses, and tiered elevations repeat formal motifs across scales, creating a visual logic that binds the smallest ornamental detail to the largest massing gesture.

Proportion is governed by traditional measurement systems that calibrate parts to the whole. Units such as the Angula, understood as the width of a finger phalange, and larger measures like the Hasta and Danda, underlie modular coordination. These measures guide the dimensions of the sanctum, halls, doorways, and vertical stages of elevation, knitting together plan, section, and ornament through a shared numerical grammar. While techniques vary by region and period, the priority of measured order remains constant, ensuring that the temple’s form resonates with its cosmological referents and ritual uses.

The broader compound is similarly ordered. Complexes can include multiple shrines, interconnected mandapas, ceremonial gateways or toranas, and water tanks known as pushkarinis. Orientation is typically east-facing, aligning the temple with solar rhythms and reinforcing the primacy of axial order. Circulation extends beyond the sanctum to encompass courtyards and exterior platforms, accommodating festivals, processions, and seasonal rites. Localized variants—in areas such as Bengal, Kerala, and Kashmir—adapt these principles to distinct materials, climates, and traditions, yet the underlying armature of sacred geometry remains a unifying thread across the regional spectrum.

Sculpture, Inscriptions & Iconography

Sculpture is inseparable from the temple’s geometric program. Carved programs entwine narrative, symbol, and ornament to amplify the sanctity structured by the plan. Deities preside at focal points, while guardians (dvarapalas), river goddesses, and celestial beings animate thresholds and transitions. Mythological narratives unfold along walls and friezes, their rhythms echoing the building’s projections and recesses. Ornamentation often adheres to fractal principles, repeating and varying motifs across scales to establish formal continuity. This self-similarity—visible in moldings, pilasters, and the multiplication of ornamental bands—creates a unified visual field that speaks directly to the temple’s cosmographic intent.

Iconography aligns with the presiding deity and regional religious traditions, with Shaiva, Vaishnava, and Jain themes shaping the sculptural ensemble. In some regions, distinctive artistic idioms become signatures of local schools. The erotic sculptures of Khajuraho, the refined bracket figures that characterize Hoysala temples, and the terracotta reliefs adorning many temples in Bengal illustrate how diverse media and narratives were woven into the architectural body. Each of these programmatic choices reinforces the temple’s ritual economy, signaling sacred thresholds, staging divine presence, and guiding the devotee’s gaze and movement.

Written records and archaeological remains complement the visual and spatial evidence. Inscriptions on temple walls, pillars, and mandapas record patronage, construction details, and ritual practices, anchoring the building’s spiritual claims in administrative and communal life. Textual sources—from Purāṇic literature such as the Matsya Purāṇa, Agni Purāṇa, and Viṣṇudharmottara Purāṇa to architectural manuals like the Viśvakarmaprakāśa, Mānasāra, and Mayamata, along with commentarial traditions such as those attributed to Utpala—offer frameworks of measurement, proportion, and ritual conduct. Epigraphic evidence supports the historical use of traditional units and proportional systems, while archaeological reconstructions corroborate the presence of circumambulatory paths, elevated platforms, and superstructures described in the texts.

Archaeological sites such as Deogarh, Sanchi, Ellora, Mahabalipuram, Khajuraho, and Bhubaneswar provide concrete, stratified testimony to the development of architectural typologies and the longevity of sacred geometric planning. Across these sites, the interplay of plan-based order, elevational hierarchy, and sculptural density is consistently observable, affirming that geometry did not merely underlie the temple’s construction but animated its iconographic and ritual life as well.

Cultural Significance

Temples articulate a set of metaphysical propositions in the medium of space, material, and ritual. Central to this articulation is the understanding of the temple as the cosmic body of Purusha, whose order and vitality the architect translates into a built form. The garbhagriha, literally the womb-house, concentrates sacred potency; it is a hinge between cosmos and devotee, where consecration rituals install divine presence. From this core radiate halls and courtyards that host the full spectrum of communal worship and cultural performance, integrating solemn liturgy with festivals, music, learning, and craft traditions.

Vastupurusha Mandala principles and associated Vastu Shastra practices align human, divine, and natural energies through measured order. The temple’s orientation, proportional harmony, and calibrated thresholds establish a setting where ritual actions are not merely accommodated but elevated. Pranapratistha, the rite of consecration, transforms a structure into a living sacred space. Through recurring festivals, daily offerings, and processions, the temple sustains community rhythms, anchoring social life within a framework of cosmic reference.

The fractal nature of temple design—where formal patterns repeat and elaborate across scales—echoes a cosmology that values self-similarity, unity, and the infinite. As devotees move from gateway to sanctum, they traverse a carefully modulated universe of forms, each threshold intensifying sanctity. Water tanks (pushkarinis) and gardens extend this cosmos to include elemental and environmental dimensions, in which purification, reflection, and community gathering find a spatial home. Thus, sacred geometry is not an abstract diagram but a living scaffold for cultural continuity and spiritual aspiration.

Visiting / Access Information

The spatial organization of temples is designed to support both ritual requirements and visitor experience. Entry often proceeds through gopurams or toranas, which frame the transition from the secular to the sacred. The axial logic guided by the Vastupurusha Mandala orients movement toward the sanctum, while mandapas provide stages for pausing, viewing, and participating in rituals. Elevated platforms and open courtyards accommodate congregations and processions, ensuring that individual devotion and collective celebration can unfold without conflict.

Pradakshina paths enable circumambulation, a practice integral to engaging with the sanctity of the shrine. Many temples are east-facing, aligning the experience of arrival and worship with solar cycles and reinforcing the symbolic transition from darkness to light. Larger complexes may include subsidiary shrines, water tanks, and community facilities, allowing for diverse devotional practices and extended stays during festivals. These arrangements also reflect climatic adaptations, with shaded halls, ventilated spaces, and layered thresholds moderating heat and guiding airflow. While each region manifests its own stylistic identity, the consistent presence of gateways, courtyards, and sequenced halls ensures that the principles of sacred geometry remain legible and accessible to visitors across contexts.

Conclusion

Sacred geometry in Indian temple design is a continuously unfolding conversation between cosmology and craft. From early Vedic altars and rock-cut precedents to the structural experiments of the Gupta period and the mature styles of medieval and later polities, the core commitment to measured order endures. Whether rising as the curvilinear shikhara of a Nagara shrine, the tiered vimana of a Dravida temple, a Vesara hybrid, or the distinct Rekha, Pidha, and Khakhara forms of Kalinga architecture, temples translate philosophical vision into tangible spatial sequences. The garbhagriha anchors this translation, while mandapas, gateways, circumambulatory paths, and platforms extend it into layered precincts calibrated to ritual movement and communal life.

Sculpture and inscriptional records deepen this architectural narrative. Mythic cycles, guardianship figures, and ornamental programs express the same geometric logics that organize plan and elevation, while epigraphy and treatises attest to the use of proportional systems and traditional units such as the Angula, Hasta, and Danda. Archaeological sites across the subcontinent corroborate the long-standing application of sacred planning and the consistent presence of elevated bases, superstructures, and circumambulatory paths associated with the sanctum’s centrality.

At the same time, several areas invite ongoing study. The precise interpretation of certain Sanskrit architectural terms, including how they were applied in practical construction, requires further philological and archaeological investigation. Scholars continue to examine the extent to which fractal geometry was a consciously formulated principle or an emergent property of iterative design and craft. Systematic, empirical correlations between textual prescriptions and extant measurements are still needed across a sufficiently broad sample of temples and regions. Likewise, the evolution and local variation of measurement units and proportional methods over time remain open to deeper inquiry, as does the influence of image-related modules on building-scale proportions. Clarifying how ritual diagrams such as mandalas were translated from canonical drawings to on-site construction practices across diverse temple types will further refine our understanding of sacred geometry in lived architectural contexts.

What is beyond dispute is the central role of geometry in aligning sacred intent with architectural expression. In Indian temples, number, grid, proportion, and ornament coalesce into environments where cosmology is not merely represented but enacted. As living centers of devotion, art, and community, these structures continue to translate ancient principles into present experience, demonstrating the enduring capacity of sacred geometry to harmonize the human with the cosmic and the built with the divine.