Printmaking in India: History, Techniques, and Cultural Legacy

Printmaking in India encompasses a long and layered history that links colonial-era technologies to modern artistic innovation and contemporary visual culture. Introduced through the printing press established in Goa in 1556 by Portuguese Jesuit missionaries, printmaking initially served religious and administrative ends. Over time, the medium became integral to vernacular print culture, public education, and political mobilization. By the early twentieth century, it developed into a recognized fine art practice, supported by institutions such as the Bichitra Club in Calcutta and Kala Bhavana at Santiniketan. In the post-independence period, printmaking was further institutionalized as a discipline within art schools, nurtured by workshops and guilds, and sustained by exhibitions across major cultural centers. Today, Indian printmaking is defined by a synthesis of technique, social engagement, and experimentation, bridging indigenous themes and global conversations.

This historical overview traces the evolution of Indian printmaking from its colonial inception to its present-day contours. It situates the medium within broader socio-political transformations, outlines distinctive stylistic developments, and introduces key artists whose work expanded both technical and expressive possibilities. The article also maps the material and institutional supports that enabled printmaking to transition from reproduction to a medium for original artistic expression, widely accessible visual narratives, and enduring cultural memory.

Historical Context

The introduction of the printing press to Goa in 1556 by Portuguese Jesuit missionaries marks the beginning of printmaking in India. Initially aligned with missionary and colonial objectives, printing technology was directed toward disseminating religious texts and facilitating administrative communication. This early stage emphasized the practical potential of the press, laying the groundwork for the more expansive roles that print would later assume in the subcontinent’s cultural life.

By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, vernacular print culture flourished across multiple regions. Missionary presses coexisted with growing indigenous participation in printing, resulting in a diversified field that included religious pamphlets, secular literature, calendars, and popular imagery. In this environment, new visual forms emerged, such as Battala reliefs in Bengal and lithographs in Punjab, which circulated through local markets and broader distribution networks. The expansion of vernacular printing facilitated literacy and language standardization, while also contributing to the formation of imagined communities that articulated regional and national identities. Distinct aesthetic features associated with local scripts, iconographies, and religious traditions developed alongside the technological spread of lithography, relief, and intaglio techniques.

Printmaking acquired a more pronounced public role during the freedom movement. Beyond serving as a vehicle for education and cultural transmission, print became a tool for disseminating nationalist ideas and mobilizing public opinion. It navigated and at times resisted colonial censorship by leveraging the reproducibility and reach intrinsic to the medium. The linkage between print and public discourse strengthened as artists and printers confronted the social reality of famine, peasant unrest, and structural inequality. During moments of upheaval, print produced urgent visual narratives attuned to the political and ethical demands of their time.

At the turn of the twentieth century, printmaking consolidated its position as both a communicative craft and a fine art practice. The Bichitra Club, established in 1915 in Calcutta, and Kala Bhavana at Santiniketan, founded in 1921, fostered technical exploration and conceptual innovation. These centers encouraged artists to consider woodcut, linocut, etching, and lithography not simply as reproductive means but as autonomous artistic languages with specific tonalities, textures, and spatial structures. The pedagogical frameworks developed in these institutions encouraged experimentation that would define twentieth-century Indian printmaking.

Mukul Chandra Dey (1895–1989) is widely acknowledged as the first Indian artist to pursue formal training in graphic art (printmaking) abroad. Between 1916 and 1917, he studied etching, drypoint, and engraving in the United States, and subsequently received advanced instruction in London from Muirhead Bone and Sir Frank Short between 1920 and 1926. Through this sustained engagement with European printmaking traditions, Dey played a foundational role in introducing and institutionalizing intaglio as a significant and intellectually rigorous medium within the modern Indian art context.

Following independence, printmaking underwent further institutionalization. Art schools across the country established printmaking departments, upgraded technical facilities, and supported research into materials and processes. The Faculty of Fine Arts at M.S. University, Baroda, emerged as a crucial training ground, while workshops and studios in cities such as Delhi, Mumbai, Ahmedabad, and Jaipur provided access to presses, materials, and collaborative networks. Studios like Baroda’s Chhaap and spaces such as the Garhi Lalit Kala Studio in Delhi contributed to a culture of mentorship, residencies, and exhibitions. The Indian Printmakers Guild, established in 1990, promoted awareness of printmaking and facilitated workshops and shows. Exhibitions, including surveys such as “The Printed Picture: Four Centuries of Indian Printmaking” organized by institutions like DAG Modern and Asia Society, helped frame historical lineages and introduced audiences to contemporary practitioners. Through these intersecting institutional efforts, printmaking maintained its dual identity as a medium of mass address and critical artistic inquiry.

While the introduction of printing technology is traceable to the colonial period, certain earlier indigenous practices and their relationship to later developments remain areas for further research. Similarly, a comprehensive history of regional printmaking beyond prominent centers such as Bengal, Santiniketan, Baroda, and major metropolitan hubs is an ongoing scholarly task. Nonetheless, across the centuries, printmaking in India consistently negotiated its role between reproduction and originality, accessibility and specialization, documentation and aesthetic invention.

Stylistic Characteristics

Indian printmaking began predominantly as a reproductive enterprise, using relief, intaglio, and planographic techniques to generate multiples of texts and images. In this early phase, technical emphasis lay in clarity, legibility, and efficient transfer of information. Relief processes such as woodcut and wood engraving yielded bold contrasts, while lithography facilitated fluid drawing and a range of tonal effects. Intaglio methods like engraving and etching enabled fine lines and detailed textures. These formal capacities complemented the functional demands of religious, administrative, and vernacular print culture.

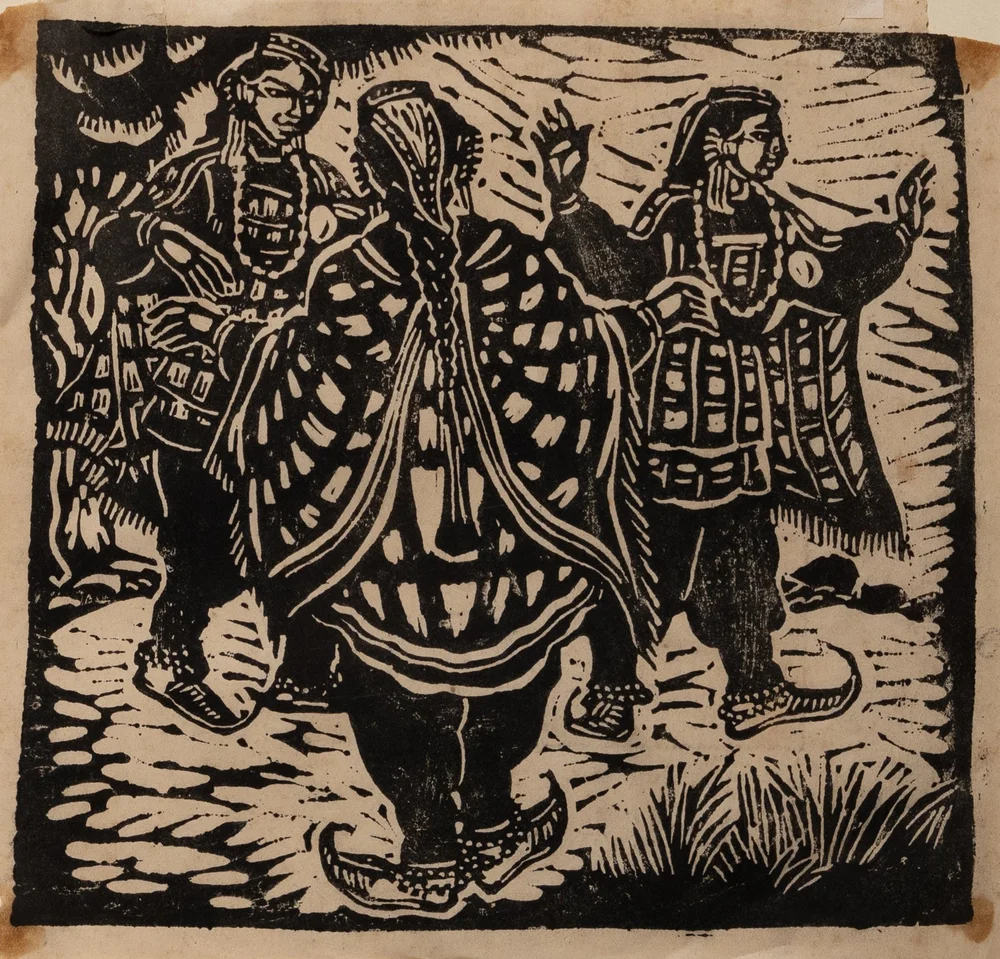

During the early twentieth century, especially in the milieu of Santiniketan, a distinct visual language coalesced. Artists sought a concise and uncluttered idiom that emphasized two-dimensionality, coherent distribution of positive and negative space, and a disciplined economy of line and tone. In relief printing, this approach translated into stark black-and-white harmonies, where compositional clarity and simplified contours were key. In intaglio, artists used delicate line work and layered textures to articulate mood and tactile surface, enriching depth without resorting to illusionistic modeling. Lithography preserved calligraphic aesthetics, particularly significant in the context of Islamic vernacular printing, where the sensibility of script intersected productively with the grease-and-water dynamics of the lithographic stone or plate.

As Indian modernism matured, printmakers experimented with new matrices and hybrid procedures. The mid to late twentieth century saw increasing use of linoleum and synthetic substitutes for wood, allowing for smoother cutting and a broader range of marks. Artists extended tonal vocabularies through aquatint and mezzotint, and they explored multi-plate color printing. Innovations in viscosity printing created complex polychromatic effects from a single plate, engaging with questions of process, accident, and surface. Serigraphy introduced stencil-based possibilities, reorienting composition around fields of flat color and crisp edges. These formal developments enabled artists to negotiate between figuration, stylization, and abstraction, and to align technical decisions with narrative intent.

By the contemporary period, stylistic diversity became a hallmark. Many artists combined indigenous motifs with modernist simplification, using abstraction to address memory, place, or identity. Others focused on political narratives, adapting the directness of relief and the reportage-like immediacy of the multiple image. The continuity of calligraphic and graphic sensibilities coexisted with strategies derived from photography, digital design, and experimental surfaces. Across these varied practices, the print’s essential characteristics—multiplicity, tactility, and the chiaroscuro of ink and paper—remained central to its expressive power.

Key Artists & Works

Raja Ravi Varma was a pioneer in popularizing Indian mythological and religious imagery through printmaking, particularly lithography and oleographs. By translating painted compositions into printed formats, he contributed to a broad-based visual culture in which devotional and narrative images entered homes, markets, and public spaces. This shift established the print as a vehicle for both aesthetic appreciation and widespread cultural circulation, influencing calendar art and early cinematic imagery.

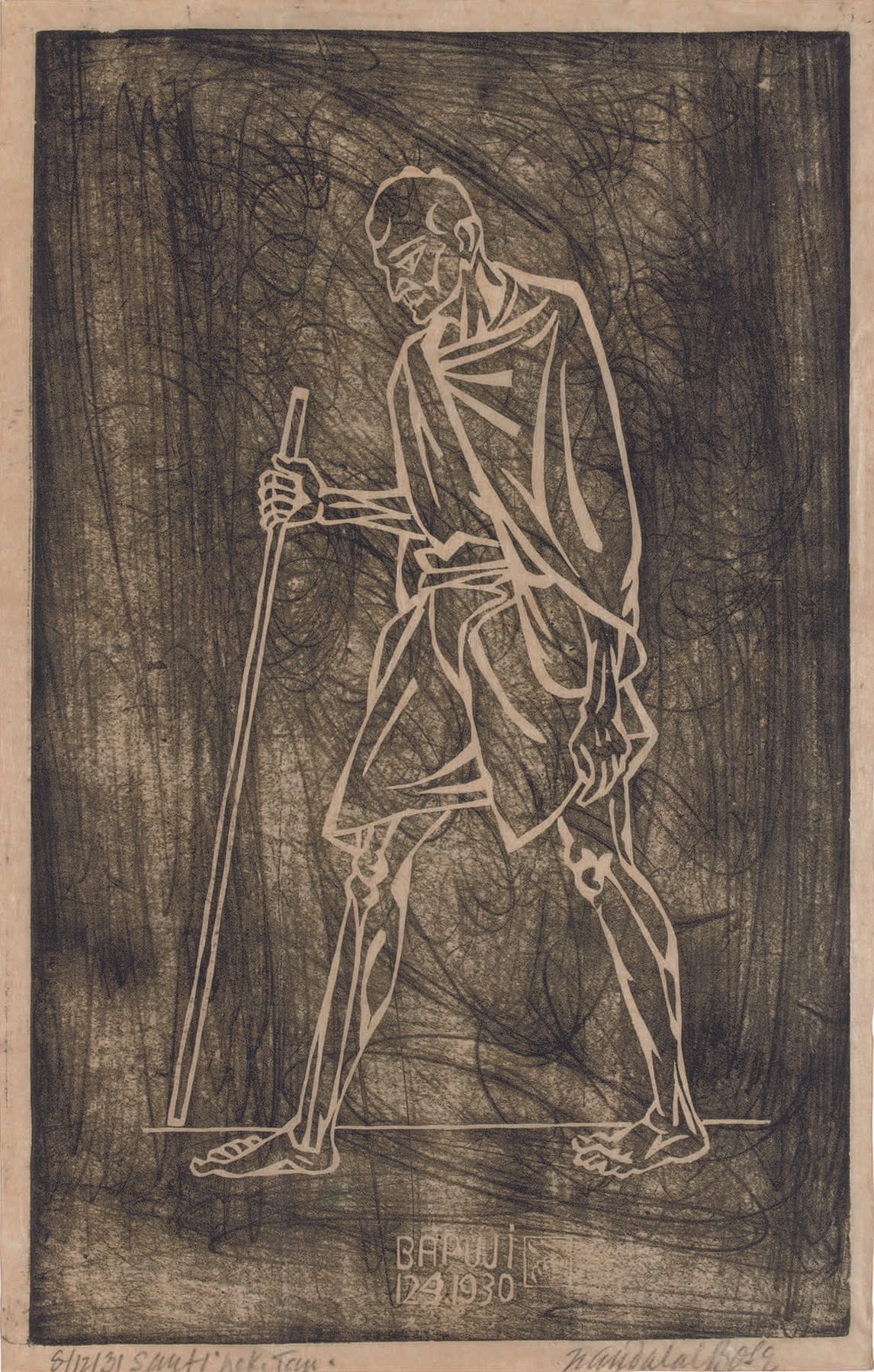

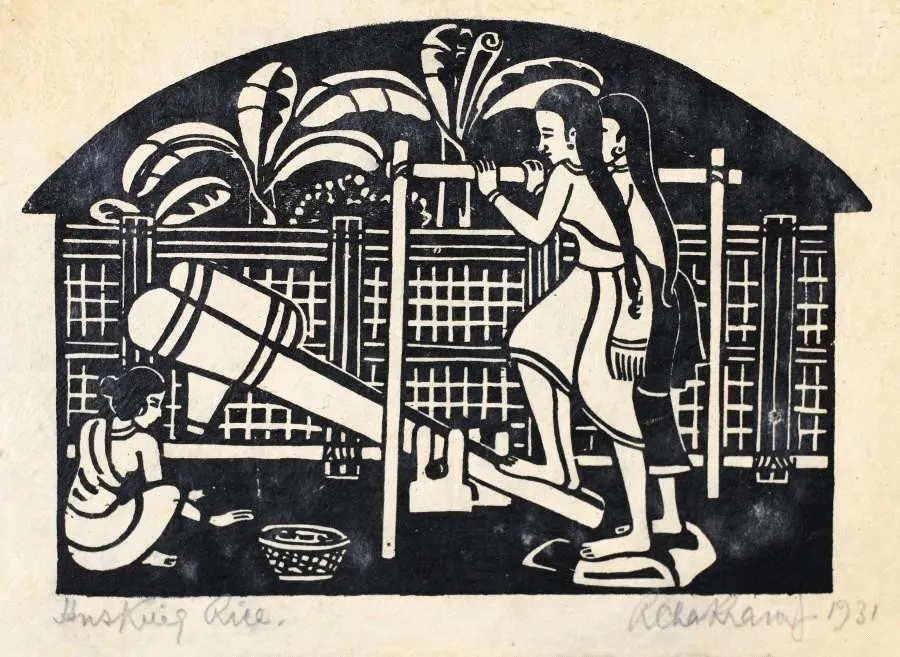

Nandalal Bose played a pivotal role in establishing printmaking within academic and studio-based contexts at Kala Bhavana, Santiniketan. His linocuts, including the widely recognized “Bapuji” (1930), exemplify the Santiniketan preference for succinct form, rhythmic line, and a harmonious balance of black and white. Bose also created illustrations for texts such as “Sahaj Path,” demonstrating how printmaking could bridge pedagogy, design, and art. His work helped to define a pedagogical paradigm in which printmaking techniques were not auxiliary but central to visual education and cultural revival.

Ramendranath Chakravorty expanded the chromatic possibilities of relief and planographic printing through color woodcuts and lithography. Engaging with the example of Japanese Ukiyo-e, he explored the interaction of contour, pattern, and hue, showing how color could be integrated structurally rather than merely as an additive layer. Mukul Dey, the first Indian artist to study printmaking abroad, mastered etching and drypoint, establishing intaglio as a compelling medium for original work in India and encouraging a deeper engagement with plate preparation, line modulation, and tonal gradation.

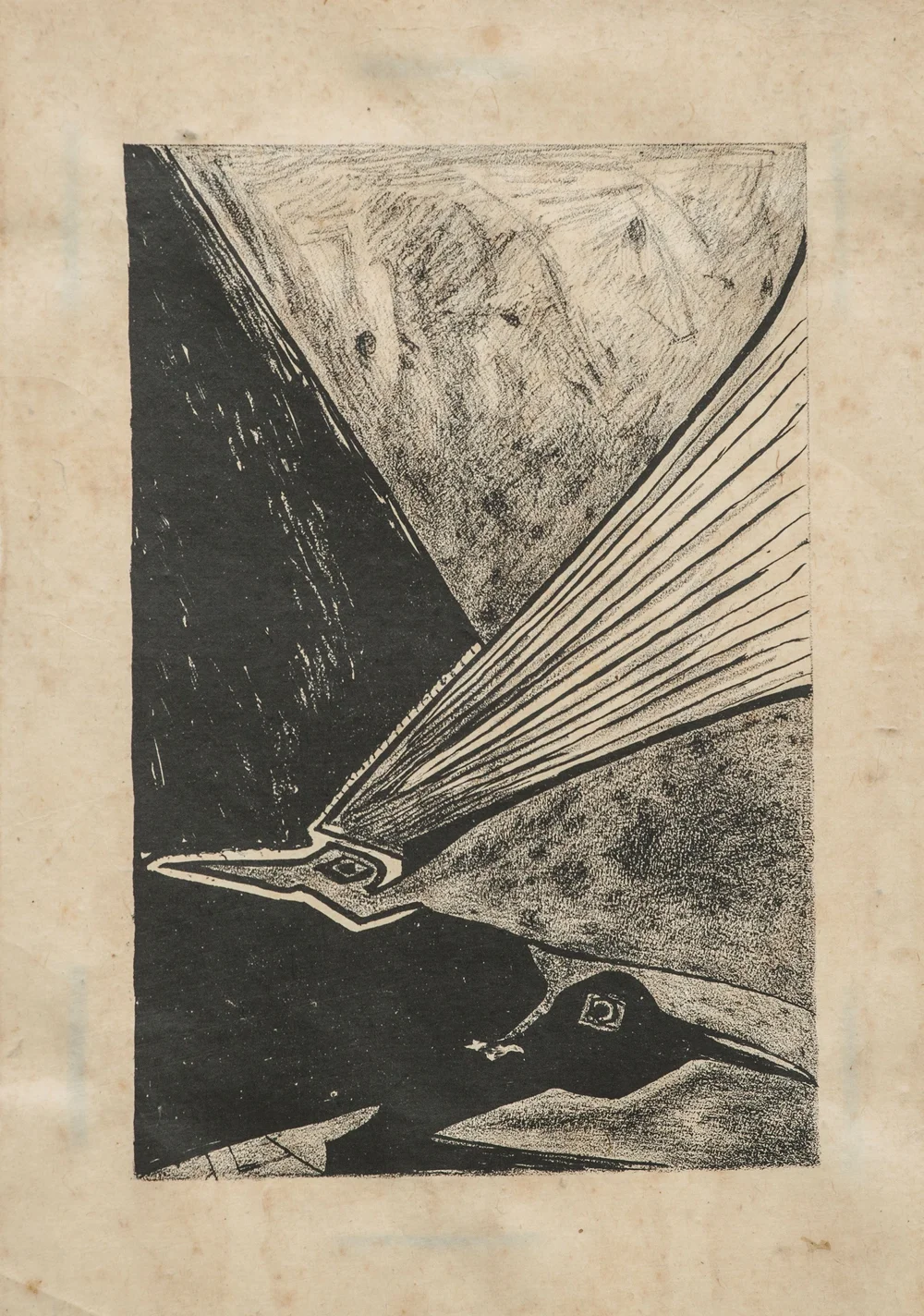

Benode Behari Mukherjee and Ramkinkar Baij, associated with the Bengal School, extended the expressive scope of print by aligning it with modernist ideas about form and material. Their work demonstrated that printmaking could sustain the same levels of experimentation and formal rigor as painting or sculpture, and that it could communicate complex visual thought without sacrificing reproducibility. Their approaches emphasized the print as a site of inquiry into structure, rhythm, and surface.

Chittaprosad Bhattacharya and Somnath Hore are central to the tradition of socially engaged printmaking in India. Chittaprosad’s woodcuts and linocuts on famine and class struggle deployed the immediacy of relief to register crisis and critique. Somnath Hore innovated with pulp prints and intaglio to express social trauma and political unrest, using the physicality of the medium to embody wounds, ruptures, and scars. In their work, material experiment and ethical urgency were mutually reinforcing, reinforcing the print’s capacity to bear witness.

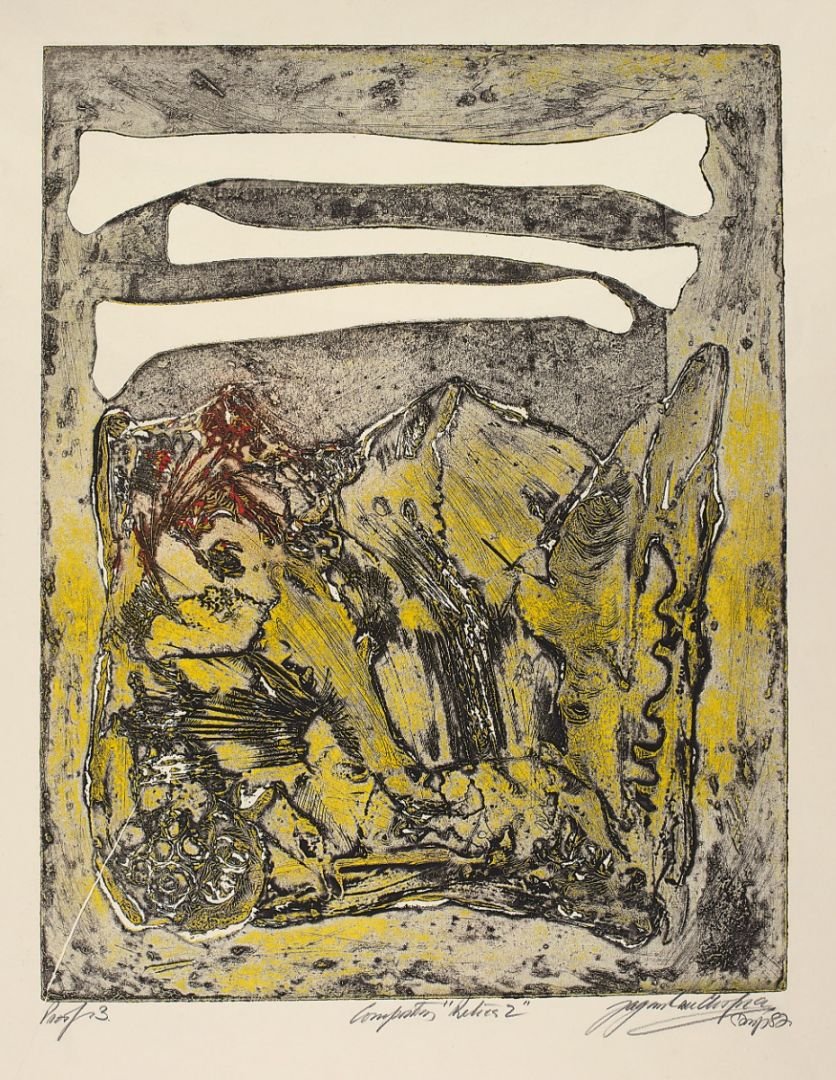

Krishna Reddy made seminal contributions to the development of viscosity printing, forging a bridge between Indian and Western approaches to technique and aesthetics. His practice affirmed the print’s experimental identity, particularly its potential for multi-color complexity without abandoning the integrity of the plate. Jyoti Bhatt, associated with Baroda, expanded printmaking’s reach by simultaneously documenting folk traditions and innovating within studio practice, thereby connecting living craft cultures to contemporary modes of production and display. K. G. Subramanyan integrated folk and classical Indian art with modernist printmaking, demonstrating the malleability of the medium as it absorbed motifs, narratives, and design principles from diverse sources.

Haren Das occupies a significant position in the history of Indian printmaking as a master of wood engraving and woodcut, whose practice was deeply rooted in the visual and cultural landscape of rural Bengal. Trained at the Government College of Art and Craft, Calcutta, he developed a refined monochromatic idiom characterized by meticulous line work, tonal gradation, and a strong sense of compositional balance. His prints frequently depict agrarian life, riverine vistas, village architecture, and pastoral rhythms, rendering them not merely as picturesque scenes but as meditations on a disappearing rural ethos. In contrast to the experimental modernist tendencies that marked certain strands of post-Independence Indian art, Das upheld a disciplined craftsmanship and narrative clarity, thereby consolidating relief printmaking as a serious and autonomous medium within twentieth-century Indian art.

Zarina Hashmi’s minimalist woodcuts distilled themes of displacement and borders into pared-down forms, harnessing the tension between absence and presence that is characteristic of relief. Contemporary artists such as Anupam Sud, Lalu Prasad Shaw, Sanat Kar, and R. Palaniappan represent the breadth of current practices, from figurative inquiry to structural abstraction. Collectively, these artists illustrate the medium’s evolution from a supporting craft to an autonomous field in which technique, concept, and social imagination intersect.

Materials & Techniques

Indian printmaking employs four principal categories of process: relief, intaglio, planographic, and stencil-based methods. Each category has distinct material requirements, workflows, and visual outcomes, shaping the artist’s choices in composition, texture, and tone.

Relief printing, encompassing woodcut, wood engraving, and linocut, involves carving away non-printing areas from a block and applying ink to the raised surfaces. The inked block is pressed onto paper, producing images characterized by bold contrasts and a graphic clarity derived from the interplay of cut lines and untouched planes. Woodcut accommodates expressive gouge marks and strong silhouettes, while wood engraving, executed on end-grain hardwood, enables finer detail. Linocut substitutes linoleum or synthetic matrices for wood, allowing a smoother cut and a different range of textures. In all cases, ink may be applied with rollers or brushes, and the physical resistance of the material informs the visual rhythm of the image.

Intaglio printing—etching, engraving, drypoint, aquatint, mezzotint, and viscosity printing—reverses the logic of relief by holding ink in incised or recessed areas of a metal plate, commonly copper or zinc. In etching, acid bites the drawn lines into the plate; in engraving, the artist incises directly with a burin; and in drypoint, a stylus raises a burr that prints as a characteristic soft line. Aquatint and mezzotint create tonal fields without reliance on line, adding atmospheric depth. Viscosity printing exploits inks of differing viscosities and the varied depths of a single plate to deposit multiple colors in one pass, enabling sophisticated polychrome effects. The intaglio workflow requires controlled plate preparation, inking, wiping, and high-pressure printing, producing prints with rich textures and subtle tonal transitions.

Planographic printing includes lithography and oleography, methods that rely on the chemical repulsion of grease and water on a flat stone or metal plate. Lithography supports gestural marks, delicate gradations, and calligraphic line, making it well suited to scripts and fluid drawing. Oleographs, related to chromolithography, disseminated color prints to broad audiences and were instrumental in the popularization of devotional and narrative imagery. The capacity of lithography to reproduce nuanced tonalities helped build connections between handwritten or drawn aesthetics and printed surfaces across diverse linguistic and cultural contexts.

Stencil-based printing, particularly serigraphy or screen printing, pushes ink through a mesh onto paper, with areas selectively blocked to build an image. Serigraphy enables vivid color planes and sharp edges, accommodating both graphic design and fine art applications. It proved adaptable to multi-color strategies and sequential layering, aligning with modern and contemporary interests in flatness, pattern, and repetition.

Over time, Indian printmakers expanded the material repertoire. Cement blocks, linoleum, and synthetic matrices complemented traditional woods; cardboard intaglio and sun mica engraving offered alternative surfaces with distinct tactile signatures. Photo-processes and digital technologies widened the field further, opening new pathways for image transfer, layering, and hybridization. These innovations complemented established workshops and institutional studios—such as those at Kala Bhavana and Baroda’s Chhaap—where specialized equipment, from presses to acid baths, supported sustained technical research and collaborative exchange.

Influence & Legacy

Printmaking in India democratized image-making and distribution. Its reproducibility allowed art and information to circulate beyond courtly or elite patronage into homes, marketplaces, schools, and public forums. This broader access reshaped cultural consumption and interpretation, making printed images central to everyday life. Lithographic and oleographic practices supported the development of calendar art and contributed visual frameworks that resonated with early Indian cinema and popular religious imagery.

The medium has been pivotal in moments of social transformation. During the freedom movement, print facilitated the spread of nationalist discourse and helped mobilize public sentiment. In the face of famine, peasant revolts, and other upheavals, printmakers employed the medium’s directness for social critique. Artists including Chittaprosad and Somnath Hore exemplify this trajectory, using relief and intaglio methods to address structural violence and collective trauma. After independence, printmaking remained aligned with nation-building initiatives, literacy campaigns, and the articulation of cultural pluralism. The capacity of prints to traverse linguistic and regional differences underscored their role in public education and in fostering a shared visual vocabulary.

Printmaking also played a decisive role in the formation of modern Indian art. Through experimentation with form, technique, and color, artists developed practices that balanced local traditions and global modernisms. Institutions such as Kala Bhavana and the Faculty of Fine Arts in Baroda nurtured generations of printmakers, integrating theory, studio practice, and critical discourse. The Indian Printmakers Guild has sustained professional networks, organized workshops, and expanded audiences. Studios in Delhi, Mumbai, Ahmedabad, Jaipur, and elsewhere contributed to a nationwide infrastructure that supports technical expertise and collaborative practice.

Exhibitions that survey historical and contemporary prints have helped consolidate the field, creating contexts in which viewers can see the continuities and ruptures across centuries. Projects such as “The Printed Picture: Four Centuries of Indian Printmaking,” presented by organizations including DAG Modern and Asia Society, have been instrumental in framing the narrative for broader publics. Meanwhile, the ongoing integration of traditional techniques with new media and digital processes has kept the medium responsive to changing technologies and artistic dialogues. This flexibility ensures that printmaking remains a vital space for innovation, able to host diverse content—from indigenous symbols to abstract structures and socio-political narratives—without forfeiting the material intelligence of ink, plate, and paper.

The legacy of Indian printmaking is thus twofold. On one hand, it is the story of a craft that evolved through pedagogy, technique, and institutional support. On the other, it is the story of images that shaped and reflected lived realities. The capacity of prints to be both intimate and widely shared, durable and responsive, positions the medium at the confluence of personal and collective histories.

Conclusion

From the first press established in Goa in 1556 to contemporary studios and exhibitions, the history of printmaking in India unfolds as a dialogue between technology, culture, and artistic intent. Initially introduced as a tool of religious and administrative dissemination, printmaking soon became central to vernacular literacies, public pedagogy, and political communication. As institutions such as the Bichitra Club and Kala Bhavana encouraged technical and conceptual exploration, printmaking transitioned from a reproductive craft into a fine art practice with its own languages of line, tone, and surface. Post-independence, the establishment of academic programs, guilds, and workshops ensured the medium’s continuity and growth, while exhibitions and studios across cities expanded its public reach.

Stylistically, Indian printmaking ranges from the bold contrasts of relief to the nuanced textures of intaglio and the fluidity of lithography, absorbing calligraphic traditions, local iconographies, and modernist simplifications. Innovations—from linoleum blocks to viscosity printing, serigraphy, and digital processes—have sustained a dynamic field that adapts to shifting aesthetic and social conditions. The contributions of artists such as Raja Ravi Varma, Nandalal Bose, Ramendranath Chakravorty, Mukul Dey, Benode Behari Mukherjee, Ramkinkar Baij, Chittaprosad Bhattacharya, Somnath Hore, Krishna Reddy, Jyoti Bhatt, K. G. Subramanyan, Zarina Hashmi, and others exemplify how Indian printmaking has continually redefined its possibilities.

As an accessible, reproducible, and materially rich medium, printmaking has democratized visual culture, contributed to education and nation-building, and fostered sustained artistic experimentation. Certain aspects—such as the extent of pre-colonial indigenous practices, detailed regional histories, and the evolving impact of digital technologies—invite further scholarly inquiry. Even so, the arc of Indian printmaking clearly demonstrates how a technology introduced under colonial conditions became a site for cultural agency, aesthetic invention, and social reflection. Its ongoing vitality rests in the balance it holds between tradition and innovation, craft and critique, the singular mark and the shared image.