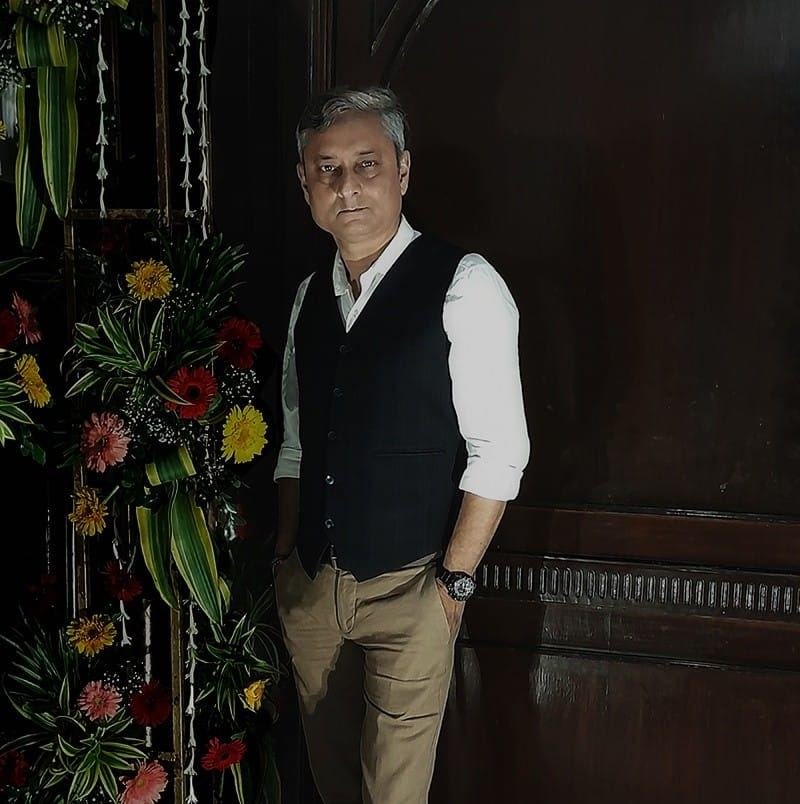

It began with a voice — calm, observant, and unhurried. On the phone from Kolkata, Joydeep Mukherjee spoke the way he photographs: with precision, with care, with pauses that hold meaning. He doesn’t talk about cameras or technique right away. Instead, he talks about people.

It began with a voice — calm, observant, and unhurried. On the phone from Kolkata, Joydeep Mukherjee spoke the way he photographs: with precision, with care, with pauses that hold meaning. He doesn’t talk about cameras or technique right away. Instead, he talks about people.

“I’m not a street photographer,” he said early on. “I photograph lives — their emotions, their endurance, their stories. The street is simply where they unfold.”

The First Frame: From Trek to Calling

Every photographer’s journey begins somewhere — sometimes in childhood curiosity, sometimes in accident. For Mukherjee, it began on the stony path to the Everest Base Camp in 2003. Then working full-time in the corporate marketing division of Exide Industries, he had packed his camera almost incidentally for what was meant to be a personal adventure. But the mountains had other plans.

“That trip changed me. I took photographs not to show beauty, but to remember how it felt to be there — to be alive among those vast silences.” The trek turned into an initiation. The stillness of the Himalayas became a teacher; the act of photographing became a form of listening.

For more than two decades now, Mukherjee has balanced two worlds — the structured rigor of a corporate life and the fluid unpredictability of human stories. He jokes about it lightly, but there’s depth in that duality: “The office gives me discipline. Photography gives me meaning.”

Vision Before Optics

Mukherjee’s artistic philosophy is as disciplined as it is instinctive. He refuses to chase gear or glamour. For years, he has worked with a single camera and one lens — the Nikon D750 with a 24–70mm. He calls it “a conscious limitation,” one that keeps him rooted in observation rather than equipment.

“I don’t need many lenses to see better. I need patience, empathy, and honesty with the subject.” He speaks of light with the respect of a craftsman but insists that it comes second: “For me, the subject is everything. The person in front of me matters more than how the light falls on them.”

This approach lends his images an unusual intimacy. Whether he is documenting the fervour of Durga Puja in Kolkata, the interiority of coal miners in Jharkhand, or the haunting quiet of an exorcism ritual in rural Bihar, his compositions seem to arise from within the moment rather than imposed from without. He listens before he photographs.

The Human Story at the Centre

Mukherjee’s photography exists in the porous space between documentation and empathy. He does not romanticize poverty or dramatize pain; he observes with care. His long-term projects often take years to mature. One of his ongoing works — a deep ethnographic exploration of exorcism practices in India — began from his academic curiosity in psychology, a field he formally keeps an interest. “I am fascinated by the human mind — how belief, fear, and superstition intertwine. Through the camera, I try to understand, not to judge.” His frames breathe with humility. There is always space — for the unseen, the unspoken, the unfinished.

Colour, Monochrome, and the Silence Between

Mukherjee’s visual language alternates bet

ween colour and black & white, yet neither is dictated by trend. He allows the story to decide. His Project Colour celebrates the lived hues of Indian life — vibrant yet grounded, where ritual and routine blur. His Project Black & White, on the other hand, seeks reduction — stripping emotion to its skeletal truth.

“Colour has its own emotion. But when colour distracts, I remove it. Black and white is not nostalgia; it’s focus.” There’s a stillness in his compositions, a restraint that resists the modern appetite for spectacle. Even in crowded festivals or chaotic streets, Mukherjee’s frames feel contemplative — as if time holds its breath.

From Maker to Mentor

But Mukherjee’s story is not just about images; it is also about community. In 2012, he founded CSFK — Click Start from Kalighat, a workshop-based initiative aimed at nurturing emerging photographers. The project began informally — a few enthusiasts walking through Kolkata’s lanes, discussing composition and ethics. Over the years, it has evolved into a collective that has travelled across India — from Pushkar to Varanasi, Ladakh to Purulia — cultivating the culture of visual storytelling.

“Teaching others teaches me. When you guide someone’s eye, you also re-learn how to see.”

Parallelly, he edits and mentors through FOTOJAJS, a digital magazine and collective that publishes photographic essays and critical dialogues. Both platforms embody Mukherjee’s belief that photography is a shared act — not a solitary pursuit of fame, but a dialogue about seeing responsibly.

Recognition, Responsibility, and Reflection

Mukherjee’s work has found its way into major publications — BBC News, Feature Shoot (USA), Dodho Magazine (Spain), Life Force (UK), 121 Clicks, The Quint — and exhibitions in India, Belgium, China, and Bangladesh. Yet, recognition, he says, is “just a milestone, not a measure.” Photography, at its core, is an act of conscience. You must decide what you’re willing to look away from — and what you cannot.”

Challenges in the Frame

Behind his calm tone lies the grind of an artist negotiating constraints — time, funding, access. Documentary photography in India, he says, survives on stubbornness. “We have few patrons, few platforms, and fewer audiences who care about long-term stories. But that’s all right. Every honest frame finds its place, even if slowly.”

He recalls moments of frustration — cameras failing in coal mines, locals refusing permission, projects abandoned due to costs. But then he laughs, almost tenderly. “Every failure teaches you humility. And humility keeps your eyes open.”

Looking Forward

Mukherjee’s future projects move toward slower, deeper storytelling. He plans to document climate displacement and migrant resilience, and hopes to expand CSFK into a more sustained mentorship and residency program for young documentary artists.

He speaks of photography not as ambition but as legacy. “Maybe years from now,” he muses, “someone will find one of my photographs and recognize a fragment of themselves in it. That would be enough.”

Epilogue: The Listener with a Lens

In the quiet cadence of our conversation, it became clear that Mukherjee does not chase photographs; he listens to them. Every image is born of patience — a moment negotiated between empathy and awareness. In his world, the camera is not a tool of conquest but of compassion.

“A good photograph doesn’t shout,” he says softly, almost to himself. “It waits. It breathes.”

In an era saturated with spectacle, Joydeep Mukherjee’s work reminds us of the quieter truths — that to see is also to feel, and that witnessing, done with sincerity, is the purest form of art. His photographs are not just windows to other lives; they are mirrors that return us to our own humanity.