Jogen Chowdhury: Line, Form, and the Politics of the Human Figure

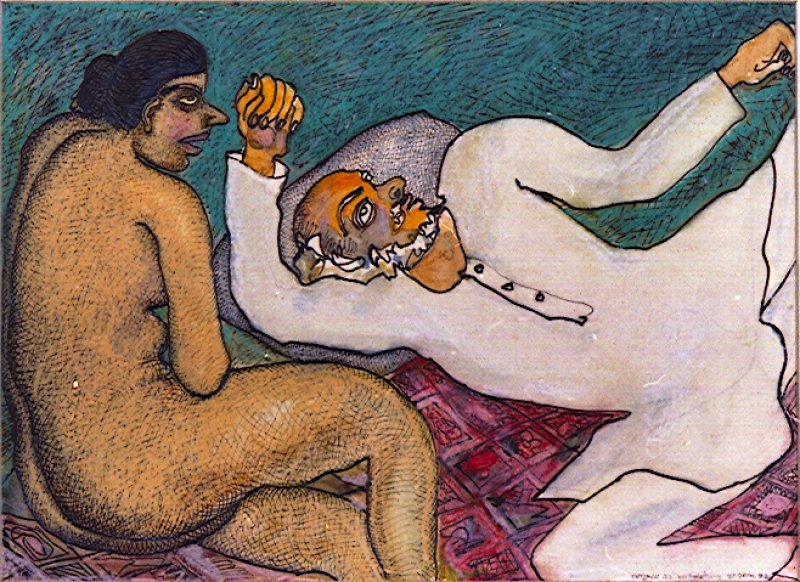

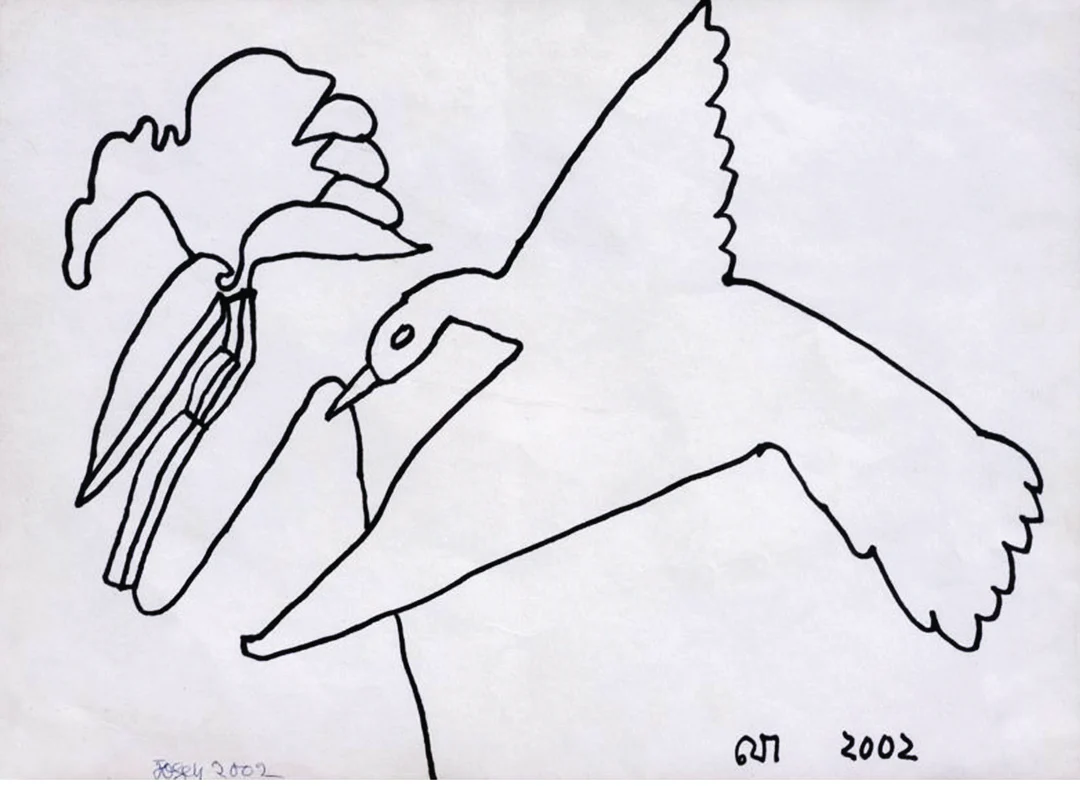

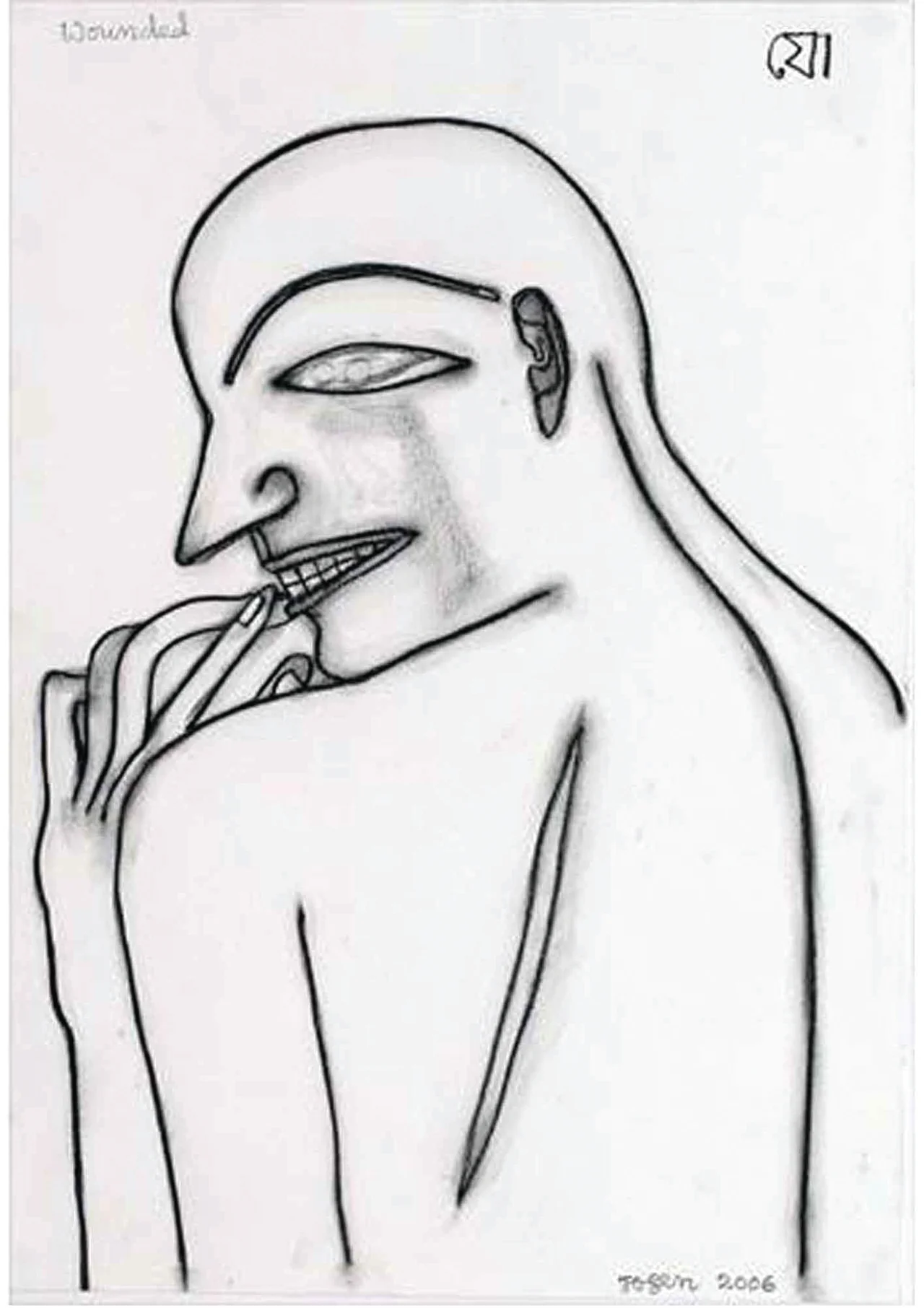

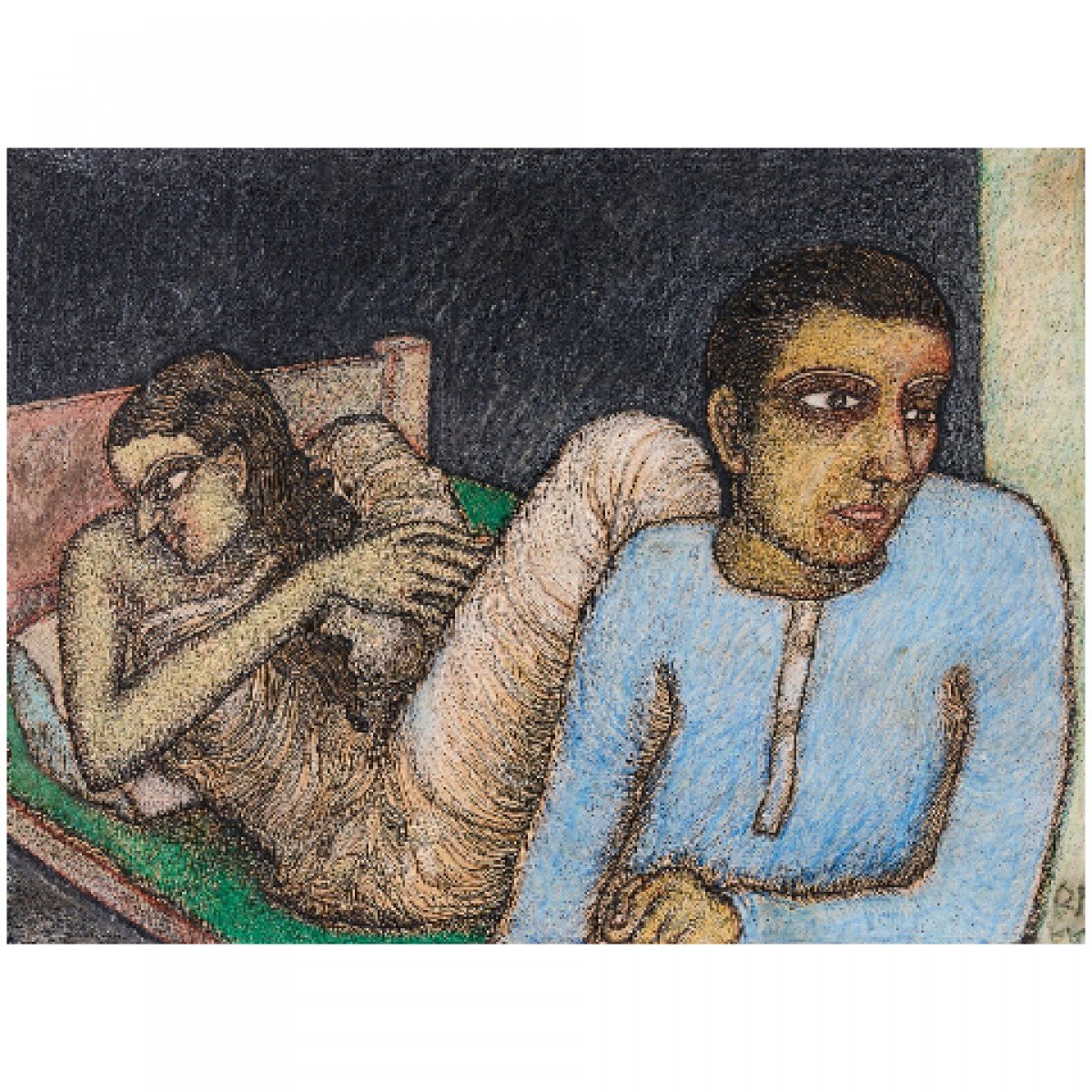

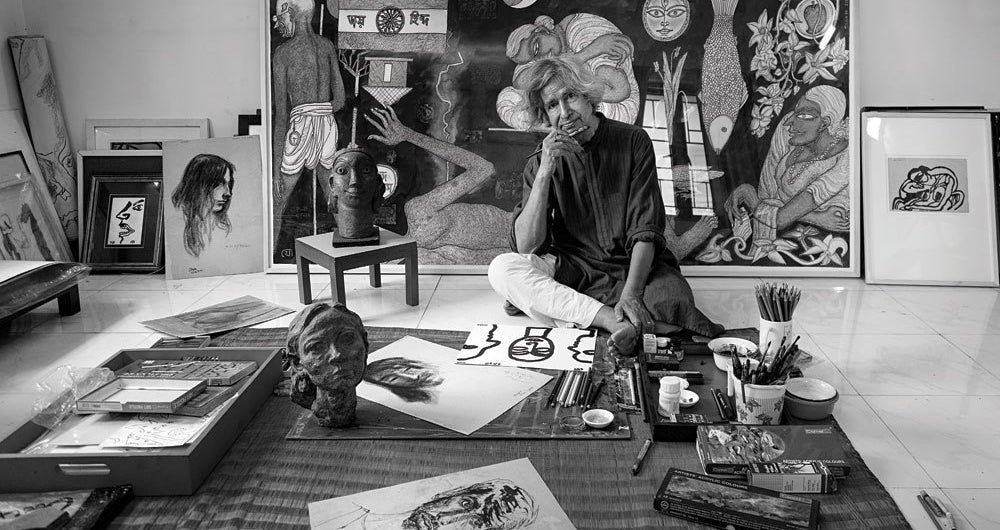

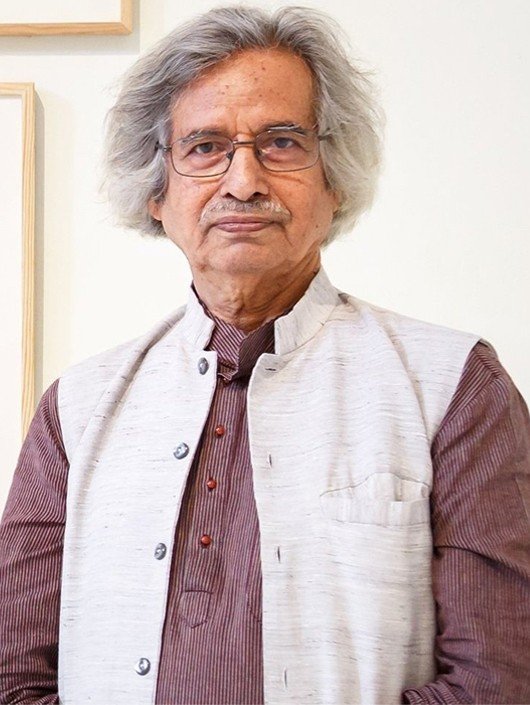

Jogen Chowdhury has occupied a singular position in the history of modern and contemporary Indian art through a disciplined, deeply personal, and incisively social approach to figurative painting and drawing. Born in 1939 in Daharpara village in the Faridpur district of Bengal, now part of Bangladesh, he came of age during seismic political changes on the subcontinent, an experience that imprinted his art with a heightened awareness of displacement, social fracture, and human vulnerability. Trained in Kolkata and Paris, and engaged throughout his life with both local traditions and global modernisms, he developed a visual language distinguished by supple, unbroken lines and a dense crosshatching technique that lends skin, fabric, and gesture an almost tactile charge. Working across ink, watercolor, pastel, and oil, as well as in printmaking and pedagogy, he has sustained a commitment to the human figure as a bearer of memory, desire, and political inscription.

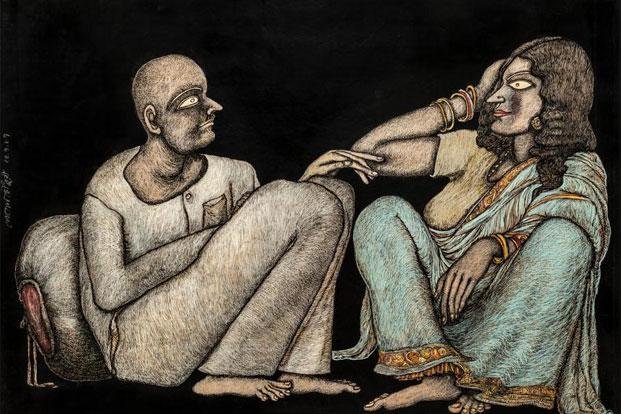

Often classified within a broad field of figurative expressionism, Chowdhury’s oeuvre resists simple categorization. The works bring together the allegorical and the observational, the mundane and the surreal, and the sensuous and the severe. Female and male bodies, couples and solitary figures, deities and animals are set within spare environments that heighten their psychic intensity. The recurring sense of estrangement and unsettledness communicates a world of shifting power, moral ambiguity, and everyday endurance. Across decades of exhibitions in India and abroad, his practice has unfolded as a sustained inquiry into the ethics and poetics of representation, and as a vigilant reflection on the pressures of history as they are marked on the body.

Early Life & Formation

The formative coordinates of Chowdhury’s life, in Bengal before and after Partition, are crucial to understanding his artistic origins. Born in Daharpara in 1939, he spent his early years in an environment where image-making was integral to domestic and devotional life. His father, Pramatha Nath Chowdhury, painted scenes from Hindu mythology, while his mother practiced Alpana, a vernacular form of ritual floor painting. This early immersion in artisanal skill and iconographic fluency introduced him to both the discipline of draftsmanship and the power of imagery to convey communal stories and intimate beliefs.

In 1947, the Partition of India precipitated the family’s displacement to Kolkata. This personal experience of rupture and relocation informed not only the themes of loss and memory that surface throughout his work, but also a sharpening of attention to the textures of ordinary life under social strain. Kolkata, a thriving center of intellectual and cultural activity, offered an intense milieu in which the young artist encountered a range of visual languages, from academic realism to the revived interest in indigenous forms that defined the postcolonial cultural climate.

Between 1955 and 1960, Chowdhury trained at the Government College of Art & Craft, Kolkata. There he was exposed to Western academic traditions alongside Indian classical and folk idioms. The duality of this education fostered a responsiveness to structure and proportion while encouraging a sustained engagement with regional forms like Kalighat Patachitra and Alpana. It also placed him in proximity to the legacies of Indian modernists such as Abanindranath Tagore and Ramkinkar Baij, whose example of assimilating local sources within experimental practices would prove consequential.

Awarded a French Government scholarship, he continued his studies at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris from 1965 to 1967, and trained at Atelier 17 under William Hayter. In Paris, the currents of European modernism and post-Impressionism broadened his visual discourse. Encounters with the work of Paul Klee, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso prompted an expanded vocabulary of form, rhythm, and color. The Paris years catalyzed a distinct synthesis: an attentive eye to the body’s expressive possibilities, refined by line and surface modulation, grounded in Indian visual sensibilities yet open to global dialogues.

Artistic Development & Style

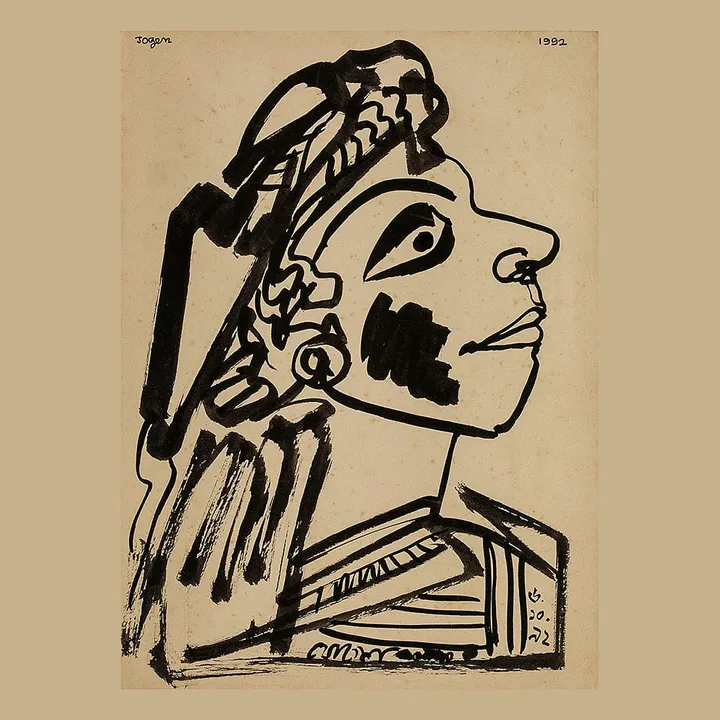

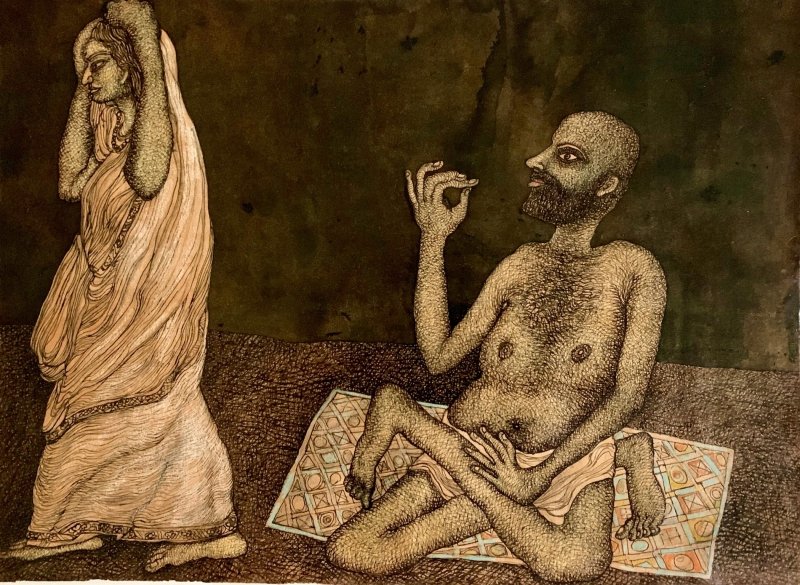

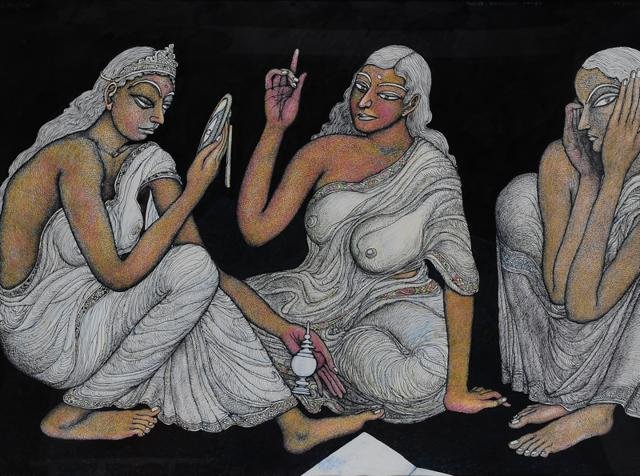

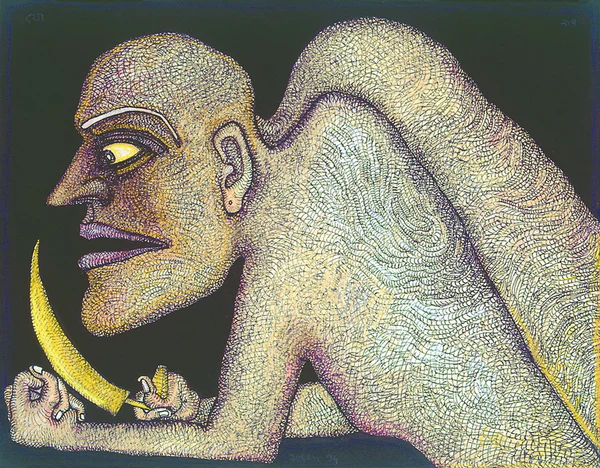

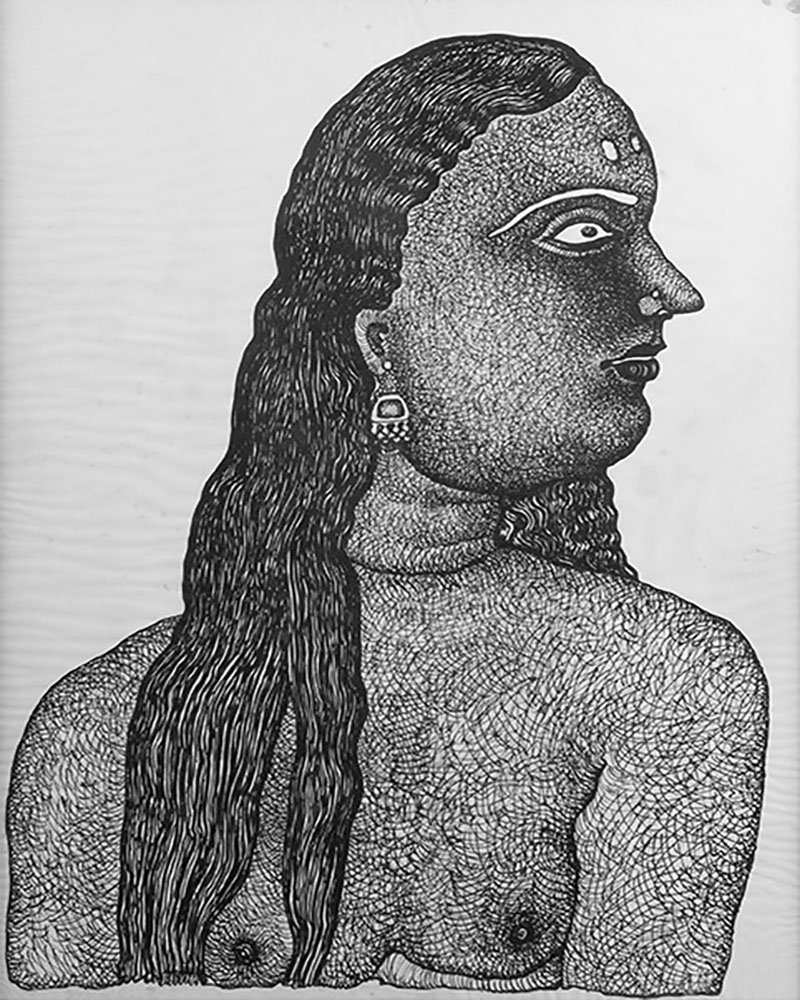

Chowdhury’s early work registers the imprint of academic training, but it is in his mature practice that a uniquely calibrated style emerges. Central to this development is the cultivation of an unbroken, fluid line that articulates contour and movement with spare eloquence. The line is never merely an outline; it is a repository of tension and flow, a conduit for the transmission of psychological states. Complementing this is his distinctive crosshatching, applied with varying densities to create the textures of skin, hair, and cloth. The accumulation of marks produces a palpable surface, one that bridges drawing and painting, and amplifies the sensorial presence of the figure.

Influences from European and Indian sources are visible, but they function less as quotations than as structural underpinnings. From Klee he distills an economy of means and a rhythmic sensibility; from Matisse a confidence in line and planar relationships; from Picasso an understanding of deformation as a vehicle for truth rather than mere distortion. From Ramkinkar Baij and Abanindranath Tagore, and from the Kalighat painters, he inherits a capacity to compress narrative intensity into gestural brevity. Folk and classical Indian idioms contribute to the symbolic vocabulary and compositional poise that underlie his images, while the discipline of Atelier 17 sharpens his engagement with print processes and experimental mark-making.

Although sometimes described as surrealist, his approach remains grounded in the real. Bodies are rarely conventional; they are stretched, weighted, exaggerated, or reassembled to render the strains of interior life and social circumstance. This distortion is never ornamental. It enacts a moral and psychological scrutiny, registering vulnerability, desire, fatigue, and defiance. Figures frequently appear against sparse or desaturated grounds, an isolation that magnifies their presence while refusing narrative closure. In works where objects or animals appear, they do so as ciphers of memory, desire, or menace, not as descriptive details.

Color in Chowdhury’s work is typically restrained. Earth tones—ochres, browns, deep greens—prevail, creating an organic register that resists decorative appeal in favor of emotional gravity. Within this muted field, occasional chromatic accents gain heightened impact, drawing attention to a hand, a wound, a breast, a gaze. The control of palette aligns with the economy of line: both strategies intensify the drama of the singular figure while sustaining a sober, reflective atmosphere.

Across media—ink, watercolor, pastel, oil, and prints—his method remains consistent in its allegiance to line as the principal vector of expression. Yet it is never merely formal. The line is a social instrument; it indexes vulnerability and power, touch and distance, intimacy and estrangement. Over the decades, this coherence of method has allowed the artist to pursue complex questions about the human condition with an insistently refined set of tools, rendering his style instantly recognizable without becoming formulaic.

Major Works & Exhibitions

Chowdhury’s corpus is both extensive and thematically consistent, with series and individual works that probe the politics of embodiment and memory. The series titled Reminiscences of a Dream, developed between 1969 and 1977, exemplifies his capacity to transform personal history into resonant visual metaphor. These works pay homage to East Bengal, invoking flora, fauna, and surreal recollections that refract a terrain of loss through sensuous, often enigmatic imagery. Memory here is neither documentary nor indulgent; it is active, reframing the past in the present’s troubled light.

Several works from the 1970s to the 1990s—among them Noti Binodi, Sundari, and Tiger in the Moonlit Night—turn to the stage of everyday life, inflecting familiar figures with socio-political undertones. The performers, lovers, and prowlers that populate these images become emblems of gendered performance, social vulnerability, and predation. In each case, the deliberately exaggerated anatomies and condensed space intensify the charged relation between subject and viewer. While the titles offer hints, they do not close down interpretation; instead, they keep the viewer’s gaze in a state of alert ethical attention.

The sustained exploration of intimacy and estrangement within relationships is a hallmark of works such as Couple II and The Couple, created across a broad span from the 1970s to 2011. These images refuse idealization. Tension, tenderness, fatigue, and desire coexist, mapped through gestures of touch, averted glances, and the uneasy choreography of limbs. The couple, in Chowdhury’s idiom, is a scene in which private negotiations of power and care mirror broader social dynamics, a microcosm of negotiation and uncertainty.

His reinterpretations of Hindu deities in works like Ganapati and the subsequent Ganesh series demonstrate the artist’s commitment to historical iconography without devotional literalism. The deity’s form, rendered with the same sinuous line and concentrated crosshatching as his human figures, absorbs the contradictions of reverence and play, benevolence and burden. The resulting images return the god to the world of laboring bodies and watchful eyes, re-siting the sacred within the rhythms and anxieties of contemporary life.

Throughout his career, Chowdhury has addressed political violence and human rights concerns with clarity and allegorical force. The Abu Ghraib series of 2005 confronts the global scandal of prisoner abuse, translating media images and reports into a language of bodies pressed, bound, and humiliated. By eschewing documentary literalism, he makes legible the universal grammar of cruelty and the erosion of dignity. More recently, the series Age of Tooth and Nail (2020) offers a symbolic meditation on violence as a systemic condition. The bestial undertones encoded in the title are worked through images that propose a society frayed by aggression, predation, and fear, yet not without the possibility of witness and ethical response.

Individual works such as Retired Horse, Face of a Young Man, Woman Face with Braid, Sleepless Night, and The Unborn Child further exemplify his ability to compress complex psychic and social conditions into focused portraits and allegories. A horse, sign of labor and endurance, is retired yet imprinted with history; a young man’s face is at once vulnerable and defiant; a braided woman, encircled by the geometry of her hair, becomes a study in containment and self-possession; an insomniac’s night is rendered through the restlessness of line; an unborn child brings forth the spectral presence of futurity laden with hope and precarity.

Chowdhury’s exhibition history reflects both steady recognition and sustained engagement with diverse publics. Early solo presentations at the Academy of Fine Arts, Kolkata (1963) and Galerie de Haut Pave, Paris (1966) positioned his work within both Indian and European contexts. Subsequent solos at institutions such as Sarla Art Centre, Chennai (1970), and the Embassy of India, Paris (1976), as well as later shows including Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi (2007), helped articulate the evolving concerns of his practice. His participation in international exhibitions and biennales—including the São Paulo Biennale (1979) and the Havana Biennale (1986), alongside exhibitions in France, Singapore, Amsterdam, Berlin, and New York—placed his figurative investigations within a global conversation about modernity, representation, and the ethics of seeing.

Major retrospectives such as Reverie and Reality (2015) and Into the Half Light and Shadow Go I (2023) have offered opportunities to survey his multi-decade engagement with line, body, and social critique. The presence of his works in significant public collections, including the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and the Glenbarra Museum in Japan, is evidence of his institutional resonance and the broader scholarly and curatorial interest his art continues to inspire.

Chowdhury’s contributions extend beyond the studio and gallery. In 1975 he founded Gallery 26 and the Artists’ Forum in New Delhi, initiatives that fostered discourse and provided platforms for contemporary practice. In 2019, he established Charubasona, the Jogen Chowdhury Centre for Arts in Kolkata, conceived as a museum and residency space that houses his oeuvre while also supporting new work and public engagement. Such institutional commitments underscore the artist’s dedication to building and sustaining art ecosystems.

Themes, Philosophy & Approach

The human figure is the fulcrum of Chowdhury’s art, not as a mere subject of portraiture but as a field of social inscription. Bodies in his images bear the marks of labor, desire, fear, and hope. They embody asymmetries of power and the costs of survival. Their exaggerations and disjunctions are not fantastical departures but acute measures of lived distortion—of how external pressures reshape internal worlds. In this sense, his figures are political without rhetoric; they articulate the stakes of existence under conditions of unrest, displacement, and inequality.

Gendered embodiment and relational dynamics recur with persistence. Women, in particular, are neither idealized victims nor abstract symbols; they confront the viewer with self-possession and vulnerability in equal measure. The man-woman relationship, often staged through the motif of the couple, becomes a testing ground for intimacy under social stress. Power circulates through glances, grips, and proxemics; even moments of tenderness carry the sediment of fatigue or the tension of expectation. Such complexity resists moral simplification, proposing instead a dense psychology attentive to affect and structure alike.

Chowdhury’s philosophy of form privileges line as an instrument of thought. An unbroken contour can unite dispersed parts of a body, hold a limb in its twist, or let a gaze drift into the empty field around it. Crosshatching becomes more than shading; it is a tactile script that lends the picture surface the grain of lived flesh. This investment in the haptic extends to his measured palette. Earthy tones keep the work not only visually cohesive but ethically grounded, avoiding spectacle in favor of a steady, concentrated attention to the body’s situation.

Spatially, his compositions often isolate figures against sparse backgrounds, a device that stresses existential presence while evacuating narrative noise. The resulting tension between fullness and emptiness allows the viewer to sense the density of what is unsaid. Although traces of surrealist thinking are evident—particularly in the conflation of dream and memory—his imagery remains tethered to the real histories that animate it. Animals, tools, and ritual objects function as signs of labor, belief, and threat, composing an iconography that moves fluently between the intimate and the social.

Beyond individual themes, the work articulates a consistent ethical stance. Even as he addresses political violence, social injustice, and human rights violations, he refuses propaganda or sentimental catharsis. Instead, he invites contemplation, implicating the viewer in the act of looking. The politics of his human figure is precisely this insistence on the dignity of attention, the rigor of form as a means of holding complexity without erasure. In doing so, he maintains a humanist commitment that is neither naïve nor detached, but grounded in the granular realities of bodies under pressure.

Critical Reception & Influence

Critics and historians have consistently identified Chowdhury as a master of line and a central voice in figurative expressionism in India. The authority of his draftsmanship, married to a sustained social intelligence, has drawn attention across generations. Reviewers and scholars have remarked on the psychological depth of his distorted figures, the clarity with which crosshatching conjures flesh and fabric, and the way minimal settings intensify emotive force. His capacity to hold empathy and critique in the same frame has been noted as a distinguishing feature of his practice.

The artist’s contribution to the broader field of Indian modern art lies in his synthesis of traditional aesthetics with the innovations of modernism and contemporary art. By drawing on Kalighat Patachitra and Alpana while engaging with Klee, Matisse, and Picasso, he established a transcultural language that is resolutely local in its references and global in its ambitions. This articulation has proved influential, not only among contemporary painters and printmakers but also in pedagogical contexts where the ethics of form and the politics of representation are central concerns.

As an educator and mentor at Kala Bhavana, Santiniketan, Chowdhury has played a formative role in shaping younger artists. His teaching and critical engagement encouraged an approach to figuration that is exploratory and socially alert, attentive to both materials and histories. The institutional presence of his works—held in the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the Glenbarra Museum in Japan, among others—has further cemented his position as a key figure within museum narratives of South Asian art.

Recognition through awards has accompanied his evolving practice. Honors such as the Prix le France de la Jeune Peinture in Paris (1966), the National Award from the Lalit Kala Akademi in India (1967), and an award at the 2nd Havana Biennale in Cuba (1986) acknowledge the breadth of his appeal and the rigor of his artistic project. Later distinctions, including the Kalidas Samman from the Government of Madhya Pradesh (2001), an Honorary D.Litt. from Rabindra Bharati University (2010), the Banga Bibhushan Award from the Government of West Bengal (2012), the Zainul Samman from Dhaka University (2016), and a nomination for the Padma Bhushan (2022), have recognized his sustained contributions to art and culture.

Beyond accolades, his influence is felt in the infrastructures of art he has helped nurture. The establishment of Gallery 26 and the Artists’ Forum in New Delhi in 1975 provided forums for exchange and visibility. Charubasona, the Jogen Chowdhury Centre for Arts in Kolkata, established in 2019, extends his legacy as a custodian of artistic knowledge, enabling the study of his oeuvre while creating opportunities for residencies and public engagement. Through these initiatives, the artist’s impact extends from the studio to the ecology of art-making and reception.

Conclusion

Across decades of practice, Jogen Chowdhury has pursued a demanding and coherent inquiry into the human figure as a site where history, desire, and power converge. Rooted in early experiences of displacement and guided by a disciplined encounter with both Indian and European traditions, he forged a language of line and surface that is immediately identifiable and persistently probing. His figures, often isolated yet resonant, convey psychological complexity without abandoning the material facts of social life. By restraining color and magnifying touch, he makes the body’s presence a matter of ethical attention.

His major series and individual works—ranging from Reminiscences of a Dream to Abu Ghraib and Age of Tooth and Nail—articulate a vigilant stance toward political violence and human vulnerability. Exhibitions in India and internationally, collections in major institutions, and a record of teaching and institution-building witness to a career that engages with both artistic form and public culture. Recognitions and awards have followed, but the core of his achievement remains a sustained commitment to seeing with care and drawing with conviction. In the enduring interplay of line, form, and the politics of the human figure, Chowdhury’s oeuvre continues to offer an essential account of modern life’s pressures and possibilities.

One Response