Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia: From Byzantine Basilica to Contemporary Symbol

In the heart of Istanbul’s Sultanahmet neighborhood, where the city’s layers of history meet at close quarters, Hagia Sophia stands as a singular architectural and cultural landmark. Officially known today as the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque, the building occupies a prominent place in the Fatih district, neighboring the Blue Mosque, Topkapı Palace, and the Basilica Cistern. Its stone, marble, mosaics, and inscriptions hold the memory of successive empires and evolving faith practices: a Byzantine basilica, a Roman Catholic cathedral, an Eastern Orthodox church, an Ottoman mosque, a secular museum, and again a mosque. This continuous palimpsest is not merely a succession of dates and names but an urban archive where design innovation and ritual use intersect, where the history of Christianity and Islam are materially embedded, and where the global heritage community looks for lessons on conservation, interpretation, and coexistence. For visitors, scholars, and residents alike, Hagia Sophia is both specific to Istanbul’s peninsula and universal in its architectural ambitions—an enduring point of reference for Byzantine and Ottoman design and a site of cultural memory with resonance far beyond its courtyard walls.

Historical Background

The story of Hagia Sophia begins in the fourth century, when the first church on the site, known as the Magna Ecclesia, was consecrated in 360 CE under Emperor Constantius II. This early structure, emerging in a Constantinople that was consolidating its role as an imperial capital, did not survive the centuries unscathed; it was destroyed by fire in 404 CE. A second basilica rose in 415 CE under Theodosius II, only to be consumed in the Nika riots of 532, a citywide upheaval that prompted a building campaign rivaling anything the Eastern Roman Empire had yet attempted. Out of this backdrop of civic turmoil and imperial resolve came the commission of Emperor Justinian I, who ordered a new and monumental church that could embody authority, devotion, and engineering prowess. Constructed between 532 and 537 CE by the architects Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus, the resulting building fused Roman spatial ambition with innovative Byzantine solutions, setting a standard by which later domed structures would be measured. Yet even this bold design faced the realities of time and tectonics: the great dome partially collapsed in 558 CE, a setback remedied under Isidore the Younger, who completed a reconstruction by 562, and additional repairs followed major earthquakes in 869, 989, and 1344. Throughout periods of stability and disruption, Hagia Sophia remained central to the religious and civic life of Constantinople. During the Latin occupation from 1204 to 1261, it was converted into a Roman Catholic cathedral, returning thereafter to Eastern Orthodox control. The turning point in its functional identity came in 1453, when Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II ordered its conversion into a mosque, initiating a new chapter that would layer Islamic architectural elements onto its Byzantine core. In 1935, the Turkish Republic, under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, secularized the building and opened it as a museum, reframing it for broader cultural interpretation and comparative study. The year 2020 marked another change in status, when it was reconverted into a mosque by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, prompting international attention and debate. Across all these phases, Hagia Sophia’s continuity lies in its capacity to be rebuilt, reinterpreted, and reused while retaining a recognizable form that signals its enduring place within Istanbul’s urban and cultural environment.

Architecture & Design

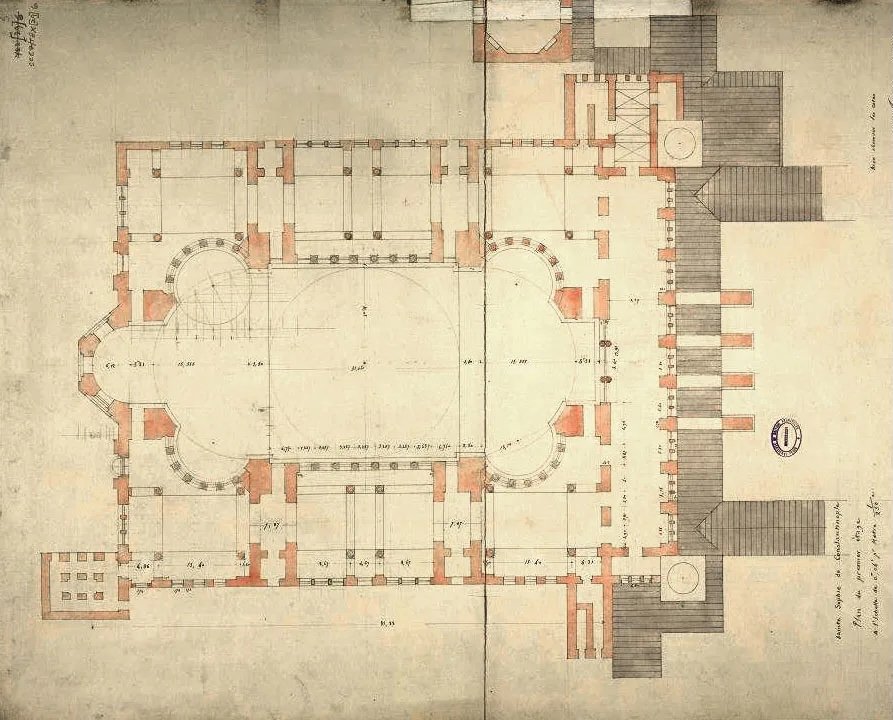

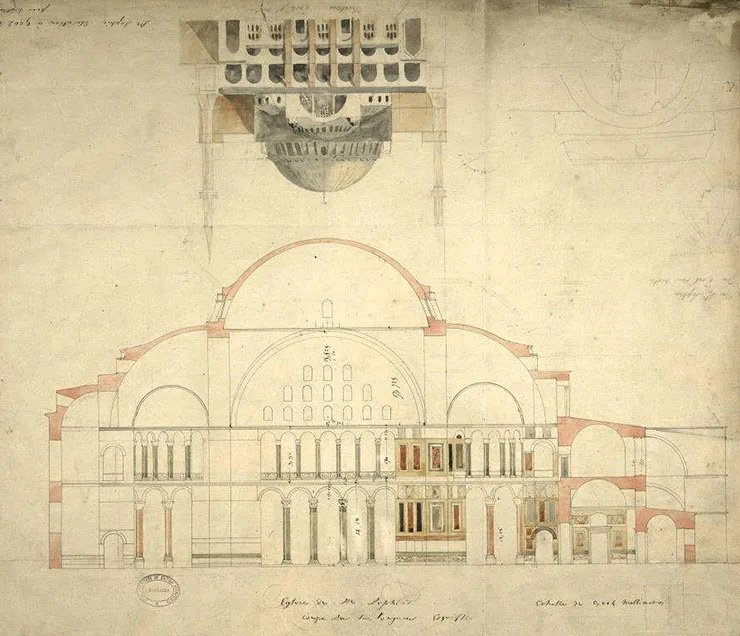

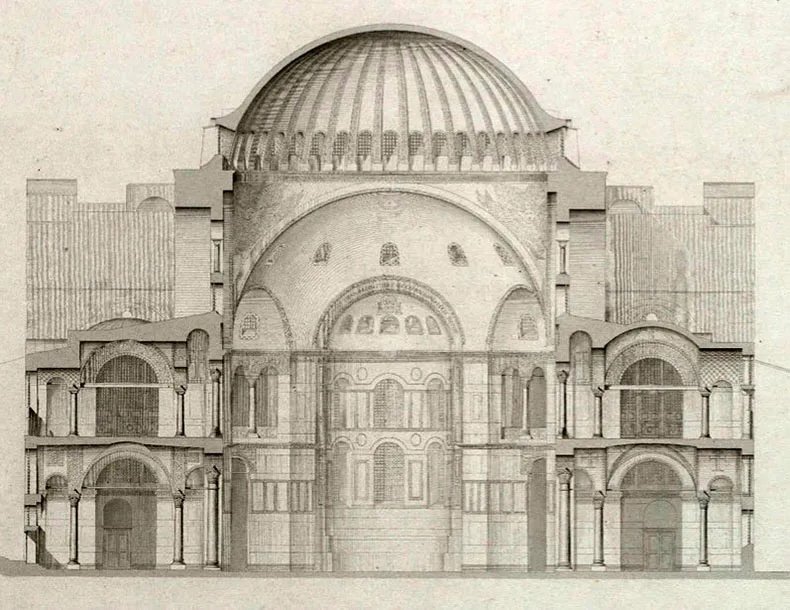

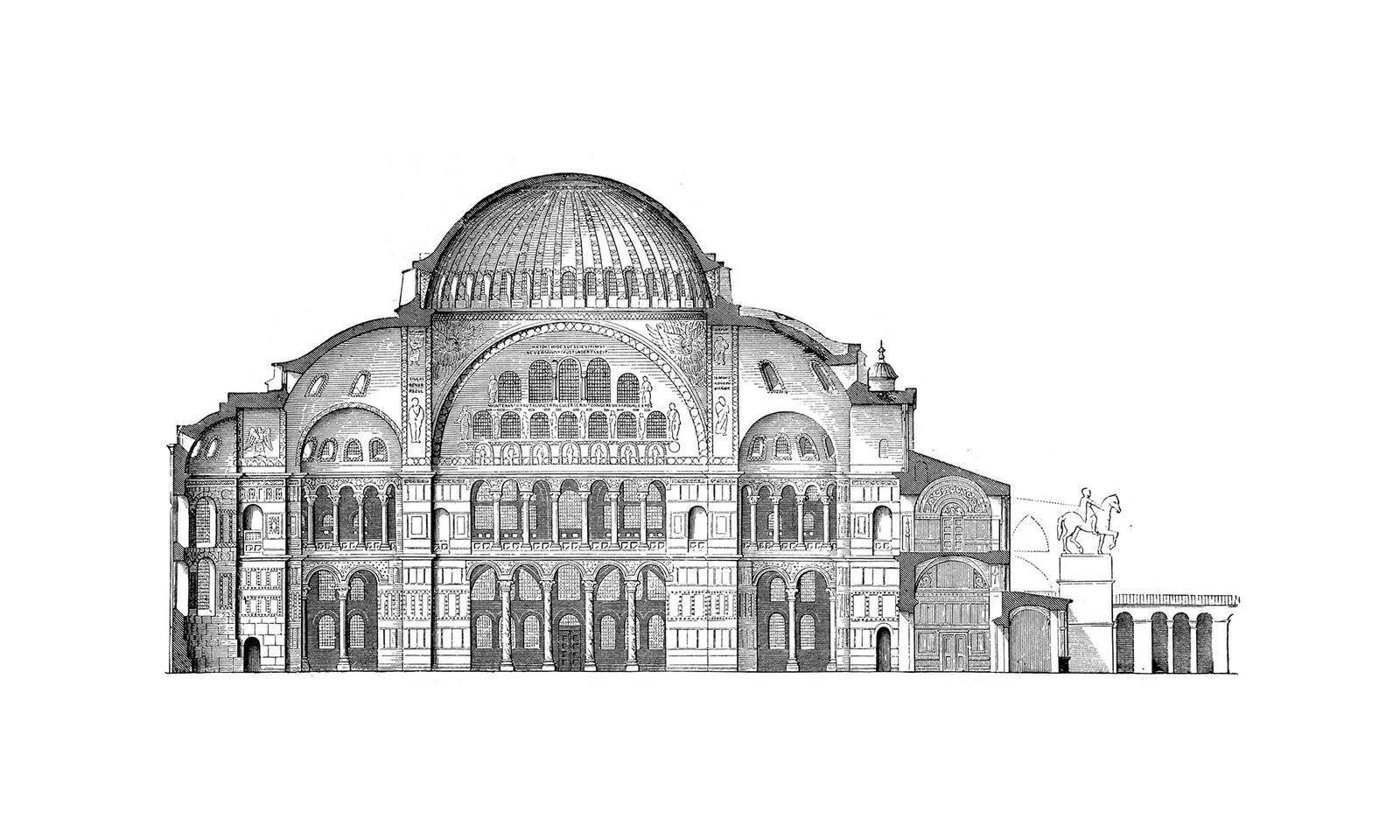

Hagia Sophia has long been recognized as a landmark of Byzantine architecture, yet the building integrates Roman, Greek, and later Ottoman Islamic influences into a cohesive whole that is both historically layered and structurally daring. Its plan synthesizes the longitudinal axis of a basilica with a centralized domed space. The main volume’s nearly square footprint supports an interior nave that opens dramatically upward to the central dome, engineering a spatial effect that balances directionality with an encompassing sense of enclosure. The dome itself—approximately 31 meters in diameter and rising to about 55.6 meters—rests on four massive piers and is transitioned to the square floor plan by spherical triangular pendentives, a solution that allowed a circular dome to crown a rectilinear base. At the drum of the dome, a ring of 40 windows admits light that, in combination with the structural shell’s curvature, produces the impression of a canopy floating above the nave. This luminous effect complements the structural logic of the building, where weight is subtly gathered and directed through arches and semi-domes to the piers and out to buttresses that were augmented over centuries to address seismic and settlement stresses. The nave’s primary load-bearing elements are flanked by semi-domes and subsidiary arches, creating a cascade of curving surfaces that modulate scale and distribute forces, while flying buttresses and additional exterior massing—from Byzantine and later Ottoman interventions—reinforce the envelope against earthquakes that have repeatedly tested the city’s architecture. The fabric of Hagia Sophia is as notable for its materials as for its form: prized stones were assembled from across the Byzantine world, including green Thessalian stone, purple Egyptian porphyry, verd antique marble, and extensive use of Proconnesian marble for the floors. These marbles, cut and arrayed to highlight natural veining and color, intensify the interior’s sense of richness, even as the core masonry remains firmly attuned to structural necessity. Decoration works with structure to guide attention and articulate sanctity. Byzantine mosaics—featuring Christian iconography such as the Virgin Mary, Christ Pantocrator, saints, and imperial patrons—originally animated key surfaces, though many were covered or plastered over after the Ottoman conquest; later, conservation efforts led to the partial restoration of some of these images. Ottoman craftsmanship layered new focal points into the space: large medallions bearing Islamic calligraphy, inscriptions encircling significant architectural lines, and the liturgical furnishings of a mosque—mihrab indicating the qibla, minbar for sermons, and a sultan’s lodge—reoriented the building for Friday prayer while respecting the monumental form of the nave. Four minarets, built at different times, frame the exterior silhouette, and mausolea and large candelabras further signal the complex’s evolution as a religious precinct. The building’s structural story continued to evolve with seismic events and changing uses. Innovations such as the reconfiguration of the ribbing in the dome and the use of squinches in subsidiary vaults contributed to stability, while Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan, renowned for his understanding of mass, thrust, and proportion, strengthened the complex with additional buttressing to mitigate structural fatigue and earthquake risk. Restoration has been a recurring theme: in the 19th century, Swiss-Italian architects Gaspare and Giuseppe Fossati undertook significant work to consolidate the dome and to reveal mosaics; in the 20th century, further conservation exposed and stabilized Christian imagery previously concealed. The World Monuments Fund placed Hagia Sophia on its Watch Lists in 1996 and 1998 due to concerns over deterioration, and a major dome restoration between 1997 and 2002 addressed critical structural and material issues. Ongoing challenges—such as salt crystallization, moisture ingress, and long-term stability—require continual monitoring. Recent preservation practice has sought a careful balance between safeguarding Christian mosaics and maintaining Islamic inscriptions and furnishings, with certain mosaics covered during Muslim prayers. UNESCO, recognizing the site’s universal value as part of the Historic Areas of Istanbul World Heritage inscription, has expressed concern over changes that may affect conservation and has encouraged dialogue and cooperation. Through these cumulative interventions, Hagia Sophia remains a living building, its design legible as a masterwork of late antiquity while its material condition reflects the stewardship and technical judgment of many centuries.

Social Context & Cultural Memory

Hagia Sophia occupies a unique place in social history and collective memory, serving in different eras as a ceremonial stage for imperial authority, a devotional center for diverse religious communities, and a touchstone for global heritage discourse. Under Byzantine rule, and especially in the age of Justinian I, the basilica signified the power of an empire that articulated its legitimacy through large-scale building and theological patronage. For nearly a millennium it served as the spiritual and administrative heart of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, hosting liturgies and rituals that shaped the religious life of the city and the broader Orthodox world. The building’s conversion in 1453 by Sultan Mehmed II reframed its meaning for a new imperial audience, becoming a political and religious emblem of Ottoman sovereignty and Islamic practice; the addition of minarets, inscriptions, and ritual furnishings embedded that identity within the building’s spatial narrative. In its long history as a mosque, Hagia Sophia influenced subsequent Ottoman architecture, providing a reference for the integration of expansive domed interiors, semi-domes, and buttressed massing in many of Istanbul’s most significant religious structures. Later, its transformation into a museum in 1935 placed it at the center of cultural interpretation, emphasizing the building’s hybrid artistry and enabling a broader public to encounter its Byzantine mosaics alongside its Ottoman calligraphy. Its reconversion into a mosque in 2020 brought new layers of meaning and discussion, underlining how such sites remain active participants in contemporary cultural life and prompting international debate about religious status, access, and conservation priorities. As a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1985, Hagia Sophia also functions as a global case study in the stewardship of multi-faith monuments, illustrating how a single building can embody the artistic legacies of different traditions while anchoring the identity of a historic district. The resulting social landscape is one of layered memory: communities attach significance to distinct periods of the building’s life, while visitors encounter an interior where Christian mosaics and Islamic inscriptions coexist. This interplay of forms and narratives shapes an evolving sense of place that rewards careful interpretation, encourages respectful engagement with difference, and reinforces the idea that urban heritage is most meaningful when it cultivates both continuity and understanding.

Visiting / Access Information

Located in the Sultanahmet area of Istanbul’s Fatih district, Hagia Sophia is easily reached on foot from other major historic attractions, including the Blue Mosque, Topkapı Palace, and the Basilica Cistern. As an active place of worship, the building is generally open to visitors outside of Muslim prayer times, and portions of the interior may be restricted during services. The upper galleries reopened to visitors in 2024, broadening perspectives on the dome, the nave, and select areas of decoration. Visitor protocols reflect the building’s current function as a mosque: women are required to wear headscarves for entry, and modest attire is expected of all visitors. After the reconversion in 2020, entrance was initially free; as of January 2024, foreign nationals are required to pay an entrance fee. Policies regarding hours, access, and ticketing may evolve, and prospective visitors should confirm details with official sources before planning. Guided tours and audio guides are available and can assist with understanding the layered narratives of architecture, faith practice, and conservation, helping visitors appreciate how the building’s form and decoration have been adapted across centuries. The most rewarding experiences often combine a careful look at the building’s structural logic—from piers and semi-domes to the pendentives supporting the central dome—with attention to the materials and motifs that record the site’s Byzantine and Ottoman chapters. Attending outside peak hours can allow for a more reflective visit, and observing respectful conduct during prayer times ensures that the living religious function of the site is maintained alongside its status as a global heritage landmark.

Conclusion

Hagia Sophia’s endurance lies in its remarkable synthesis of architectural innovation and cultural adaptability. Conceived in the sixth century as a statement of imperial ambition and spiritual grandeur, it has been shaped by earthquakes and repairs, by liturgies and sermons, by mosaics and inscriptions, by curators and conservators. Its Byzantine core—anchored by pendentives, a luminous dome, and polychrome marbles—has proven resilient enough to receive Ottoman additions that recalibrated the building for Islamic worship without erasing its earlier identity. The resulting monument stands as both a technical milestone and a reflection of Istanbul’s status as a crossroads, where art and ritual from different traditions intersect within a single monumental volume. As a UNESCO World Heritage Site and an active mosque with a complex museum legacy, Hagia Sophia invites ongoing stewardship that respects its intertwined histories and addresses conservation challenges ranging from structural stability to moisture and salt crystallization. It also calls for interpretive practices that allow visitors and worshippers to recognize the integrity of each layer without privileging one at the expense of another. In this, Hagia Sophia offers a framework for understanding multi-faith and multi-period monuments across the world: architecture can outlast regimes and reframe rituals; materials can carry meaning across time; and careful, informed care can protect a building’s universal value while honoring its living function. The monument beside the Hippodrome and the palace walls continues to orient the cityscape of Istanbul, not as a relic locked in the past, but as a vital presence that connects empires to the present and architectural brilliance to everyday life.