Ganesh Pyne and the Poetics of Darkness

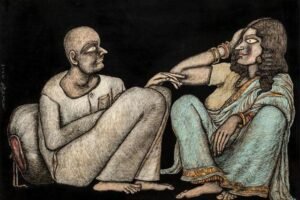

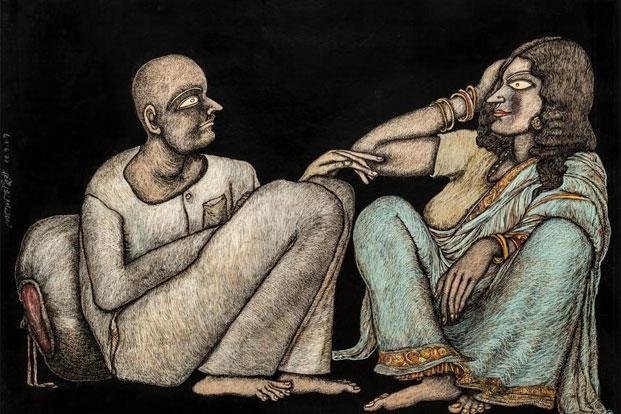

Ganesh Pyne stands as a singular presence in Indian modern art, a painter whose language of shadow, memory, and allegory gave modernism in India one of its most inward, sustained, and intricately crafted voices. Associated with the legacy of the Bengal School of Art and working within the broader ambit of Indian modernism, he developed a distinct pictorial idiom that he himself characterized through a sensibility akin to poetic surrealism. His chosen medium of tempera, cultivated after early explorations in watercolor and gouache, allowed him to build diaphanous layers of color and light that carry the gravity of his themes: death, melancholy, solitude, and the fraught intersections of myth and lived experience. Rooted in the cultural memory of Kolkata and nourished by Bengali folklore, he created a visual theater where haunted figures, masked presences, skeletons, and animals with human traits occupy imagined spaces of stillness and ambiguity.

Born in 1937 and trained at the Government College of Art & Craft, Kolkata, Pyne drew early on from the romantic and symbolist aura of the Bengal School; at the same time, he was attuned to the subtlety of line and abstraction in European modernism and to the chiaroscuro of old master painting. He also absorbed narrative strategies from animation and from the measured authority of European auteur cinema, shaping an art that is narrative without being illustrative, cinematic without being theatrical. His works have been shown across India and internationally, including at the Paris Biennale and at prominent exhibitions in London, Washington, DC, West Germany, Japan, and Singapore. While his practice was circumspect and his public presence restrained—his first solo exhibition took place after he had turned fifty—his stature has continued to grow through retrospectives and ongoing scholarship.

Pyne’s contribution to art history is anchored in his ability to bridge tradition and modernity without collapsing one into the other. He revitalized mythic and folkloric subjects by staging them within a modern psychological horizon, pursuing a painterly language that carries the intimate scale of memory as well as the austerity of metaphysical inquiry. The following account traces his formation, the evolution of his style, his recurring themes and motifs, and his place within the critical discourse of Indian art.

Early Life & Formation

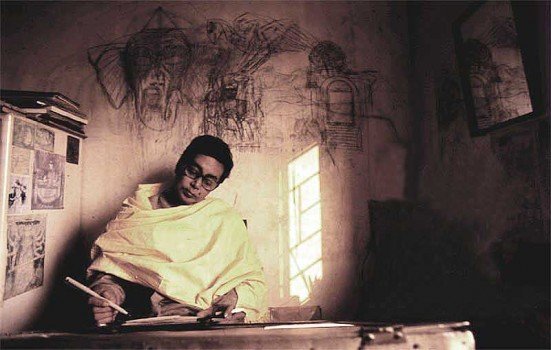

Ganesh Pyne was born on 11 June 1937 in Kolkata, then Calcutta, a city whose cultural ferment and historical turbulence would later inform the tonality of his work. He spent his early years in a decaying family mansion on Kabiraj Row in North Kolkata, an environment thick with the vestiges of a bygone household life. The setting of this childhood—its long corridors, layered shadows, and quiet recesses—has often been understood as an atmospheric seedbed for the introspective temperament that would mark his art. Yet the materiality of place was only one strand; the other, more arresting strand came from the psychic ruptures he experienced early on.

Among the most formative events was the loss of his father in 1946. The same year brought the Calcutta riots during Direct Action Day, which exposed the young Pyne to the immediacy of violence and death. These experiences are not incidental to his later subjects; rather, they appear to have etched a profound sense of mortality and fragility into his imagination. The haunted calm and the poised stillness that dominate his mature paintings acquire a tangible context when read alongside this early exposure to loss and instability.

At the same time, his childhood was nourished by a countervailing source: the storytelling of his grandmother. Through her, he encountered Bengali folklore, mythic episodes, and the moral fables that circulate within the region’s oral traditions. This intimate education in narrative—not as doctrine but as living tale—shaped his sense of pictorial narrativity. It encouraged an approach to imagery that is oblique and allusive, where characters and creatures are endowed with symbolic charge without surrendering their enigmatic presence.

As a child and adolescent he read Bengali children’s magazines and encountered the art of Abanindranath Tagore, a founding figure of the Bengal School of Art whose romantic and symbolist leanings would resonate with Pyne’s own inclinations. These early exposures gave him a sensibility for lyrical mood and for the atmosphere of story. He enrolled at the Government College of Art & Craft, Kolkata, graduating in 1959. Although he joined the department of Western painting, with its emphasis on European techniques and forms, he found himself equally drawn to the currents of oriental painting and to traditional Indian art. That oscillation—between Western academic discipline and an Indian pictorial inheritance—became an engine of his formation rather than a contradiction to be resolved.

Before he settled into the tempera practice that would become his signature, Pyne worked in watercolor and gouache. An early watercolor, Winter’s Morning (1955), suggests the quiet observational tenor of his beginnings. It also anticipates his sensitivity to muted light and to mood over incident. His professional path during and after his formal studies included work as a draughtsman and an animator, and he trained at Mandar Studios under Clair Weeks, a Disney animator. There he participated in animation projects based on Indian fables—drawn from the Hitopodesh and the Panchatantra—in a format influenced by Walt Disney. The animation experience sharpened his understanding of expressive exaggeration, rhythmic pacing, and the narrative potential of minimal means, resources he would transpose into painting without adopting the outward mannerisms of the animated film.

Artistic Development & Style

Pyne’s earliest artistic allegiances were to the Bengal School, above all to the romantic and symbolist language of Abanindranath Tagore. That inheritance can be traced in his sensitivity to atmosphere, in his distaste for overt spectacle, and in his pursuit of refined tonal transitions. He also registered the graphic clarity and compositional wit of Ganganendranath Tagore. These points of departure did not constrain him; rather, they opened into a dialogue with European art and cinema that deepened the complexity of his painterly thinking.

From European painting he engaged, in particular, with the use of chiaroscuro associated with Rembrandt. For Pyne, the play of light and shadow was not simply a technical option but a dramaturgical resource: it could introduce mystery, heighten emotional pitch, and lead the viewer as much by veiling as by revealing. His interest in the line and abstraction of Paul Klee encouraged an economy of form and a belief in the expressive autonomy of signs and marks. Avoiding descriptive literalism, he often allowed contour and surface patterning to carry a symbolic charge, so that the reality on the canvas was as much an inscription of thought as a representation of things.

His engagement with cinema—particularly with the European avant-garde corpus represented by Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman, Andrei Tarkovsky, and with Satyajit Ray—contributed to a pictorial sense of temporality, to an architecture of frames and intervals in which time seems held in abeyance. The films he admired favored internal states, situations of isolation, and metaphysical quandaries, concerns that dovetailed with his own thematic preoccupations. Even when a Pyne painting appears to capture a static moment, it implies a sequence before and after, a suspended narrative arc located more in the viewer’s consciousness than in any external storyline.

Technically, Pyne moved from watercolor to gouache before arriving at tempera, the medium that became synonymous with his practice. Tempera, with its capacity for layering translucent colors, allowed him to build surfaces where depth emerges from within rather than from illusionistic perspective. The resulting skin of paint has a luminous density, a matte radiance well-suited to the atmospheric pressure his subjects demand. His palette gravitates to dark hues—blacks, deep blues, ochres—against which small calibrations of light operate with heightened effect. Chiaroscuro, in his hands, is less a contrastive device than a method for infusing stillness with tension.

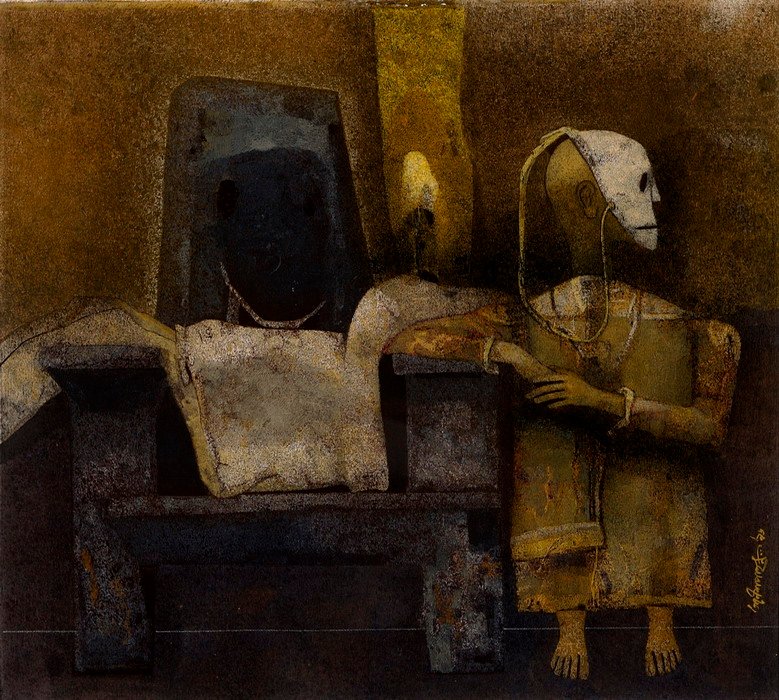

The influence of animation is visible not as cartoon flourish but as an ability to render expressive intensity through spareness, to activate faces, masks, and skeletal forms with a concentrated, sometimes exaggerated, emotion. Figures are pared to essentials: a skull, a gloved hand, an animal’s head with a gaze that registers more than it declares. The narrative order of his paintings is constructed less through explicit action than through spatial configuration, metaphor, and the orchestration of symbolic motifs that recur across decades.

This confluence of sources yielded an approach that critics have often described as poetic surrealism. The phrase suits the tenor of his art: fantasy arrives not as escape but as a precise vehicle for existential inquiry. In Pyne’s paintings, the real and the imaginary meet at a point of equipoise where metaphysical dread and tender memory, theatrical mask and vulnerable face, ritual and reverie, share the same deep air.

Major Works & Exhibitions

Pyne’s oeuvre unfolds over five decades, during which he sustained an exacting standard of craft and a repertoire of images that, while evolving, retained their internal coherence. Among his early works, Mother and Child (1961) shows the balance of tenderness and unease that will later distinguish his mature period. It is emblematic of his ability to assign gravity to a universal subject without resorting to sentimentality, and to suggest unspoken narratives through posture, gesture, and light.

By the early 1970s, his tempera practice was fully developed. The Harbour (1971) positions its viewer in a zone where structure and emptiness hold each other in tension. Absent overt bustling detail, the painting likely relies on tonal modulation to secure an atmosphere of watchful quiet. In The Teeth (1978) and The Assassin (1979), menace is condensed into image-fragments that function like emblems. The presence of skeletal or blade-like forms intimates violence without descriptive event, underlining Pyne’s preference for symbolic concentration over literal depiction.

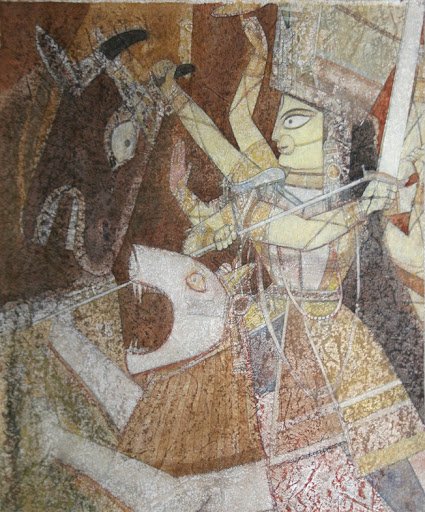

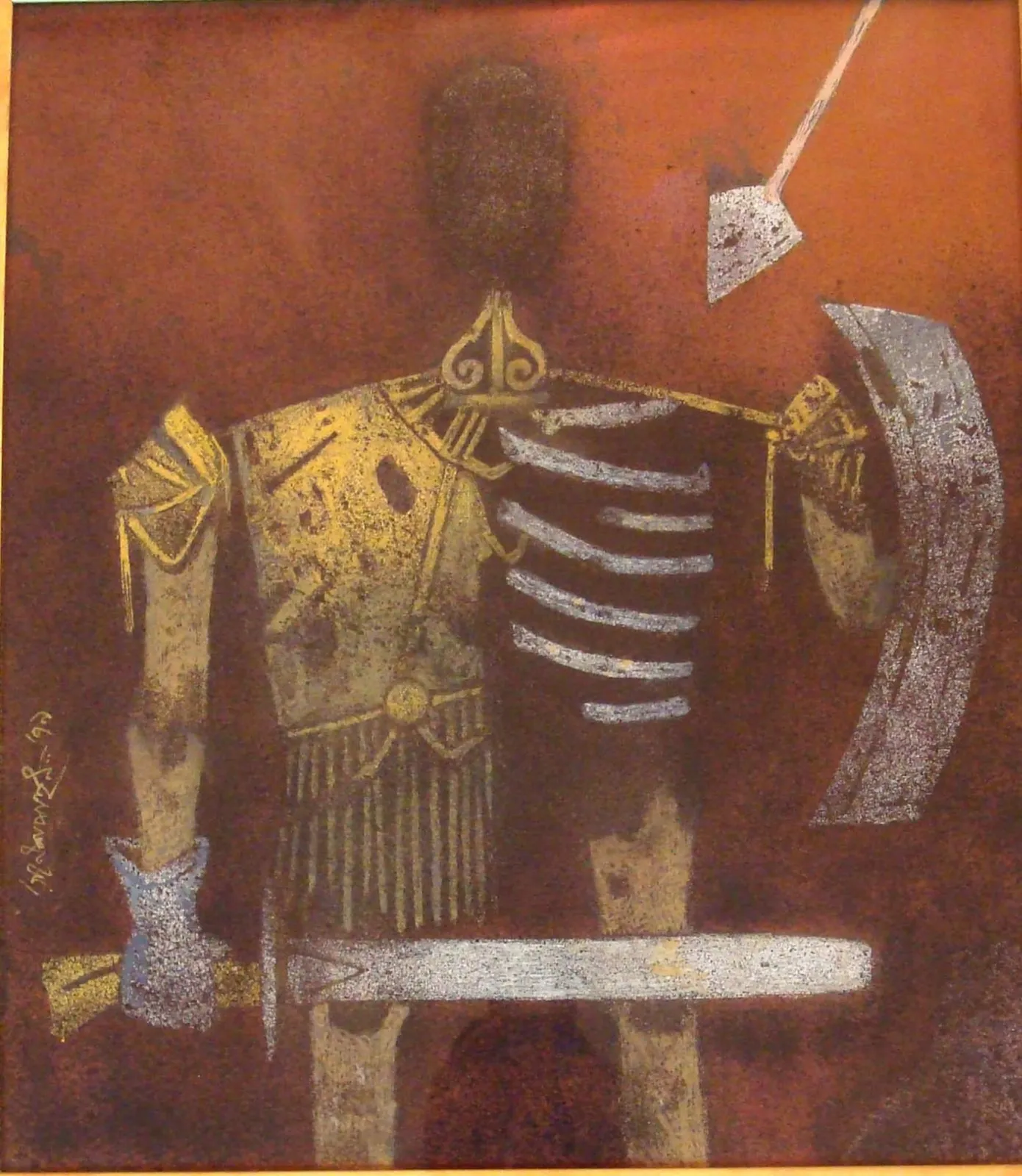

Works from the 1980s and 1990s include The Night of the Merchant (1985), where a solitary figure occupies an ambiguous space—neither wholly mythical nor strictly urban—suggesting the psychic burden of commerce and the human condition as a kind of transaction with fate. Bir Bahadur (1989) takes up the figure of a warrior, not as an extrovert spectacle of heroism but as an archetype filtered through mask and memory. Ape and the Flower (1990) stages the contact between animal and plant, perhaps as a parable of desire and fragility, while Savitri (1999) revisits a mythic protagonist to explore steadfastness and the border between life and death, a boundary central to Pyne’s cosmology. These works crystallize his consistent engagement with allegory through compacted imagery, a method that makes reading and re-reading a core feature of encounter with his art.

Pyne also developed a series on peripheral figures from the Mahabharata, exhibited in 2010. By focusing on characters such as Ekalavya and Amba, he redirected attention from canonical heroes to those whose stories circulate on the edges of epic narrative. This shift is consistent with his general approach: a fascination with the margins of events, with the hush before and after decisive acts, and with the lives that history acknowledges only glancingly. Placing such figures within his atmospheric schema, he recast epic material as a matrix for modern ethical and existential thought.

His exhibition history maps the spread of his reputation beyond Kolkata and India to a wider circulation. He participated in the Indian International Triennial in 1968 and 1971 and in the Paris Biennale in 1969. Throughout his career, he featured in shows in West Germany, London—including at the Royal Academy of Arts—Washington, DC, Japan at the Glenbarra Art Museum, and the Singapore Art Museum. These appearances registered the international curiosity about Indian modernism and about the distinct registers it could adopt. Despite this growing visibility, Pyne maintained a careful pace domestically; his first solo exhibition took place at The Village Gallery, Delhi, only after he had turned fifty, a fact that resonates with his reticence toward the public spotlight.

Institutionally, his work has been consolidated through retrospectives and posthumous exhibitions. A major retrospective was organized by the Centre of International Modern Art (CIMA), Kolkata, in 1998, drawing together multiple phases of his practice and offering an opportunity for sustained critical viewing. Subsequent exhibitions have continued to frame his legacy: Memorialising Ganesh Pyne at Akar Prakar, Kolkata in 2020, and From the Shadows at Akar Prakar, Delhi in 2022, both extended the continuity of engagement with his art. His works are present in private and public collections, and they have circulated through auction platforms including Christie’s, indicating a persistent collector interest alongside scholarly attention.

Themes, Philosophy & Approach

Death is not an isolated theme in Pyne’s work but the horizon within which other subjects acquire significance. The presence of skulls, skeletons, and masked figures is less a memento mori than an inquiry into what remains when worldly definitions slip away. In his paintings, death is both the terminus and the measure against which feeling and memory define themselves. Melancholy, solitude, and existential anxiety are corollaries of this orientation, and yet they do not lead to despair; they enable a depth of concentration in which care—for stories, for faces, for fragile rites—finds its contours.

The lexicon of his imagery is notably consistent. Masks register the double account of identity: protection and concealment on one hand, role and ritual on the other. Ghostly presences haunt the picture plane as if straddling thresholds between epochs, acting as witnesses rather than protagonists. Animals with human traits—an ape contemplating a flower—imbue the world with sentience and irony, displacing the human from its position of interpretive mastery. Through these images, Pyne formulates a moral and metaphysical theater in which every object is possibly a sign and every sign is a possible pivot of narrative.

His color is foundational to this theater. He prefers deep blues, blacks, and ochres, not as mere indicators of sadness but as the spatial condition of a distinctive psychic climate. Against these fields, minute inflations of light carry great leverage. The chiaroscuro he learned from studying European masters becomes a grammar for modulating silence and disclosure, for pressing the viewer close to the surface and then releasing them into imagined recesses. Tempera reinforces this dynamic: its layered translucency sustains a surface that reads like time sedimented, where decades of motifs can reappear as if from behind a veil.

Pyne’s relationship to narrative is elliptical. Stories are present, but they proceed through setting and emblem rather than through linear sequence. A figure stands poised, a hand reaches, a merchant waits, an assassin hovers—not at the height of action but at the cusp where intentions harden into acts or dissolve back into uncertainty. The viewer is asked to reconstruct a world out of fragments, a process that mirrors the operations of memory itself. Indeed, memory—personal and cultural—is a through-line of his art. The grandmother’s tales of Bengali folklore and the epics of the subcontinent do not appear as illustrated episodes; they are transformed into archetypal situations that speak to contemporary conditions without losing their rootedness in older narrative economies.

This is where Pyne’s position between tradition and modernity is most evident. He neither rejects mythology nor submits to it; he appropriates its expressive resources to address modern dilemmas: loneliness amid public life, the ambiguities of power, the endurance of grief. His series on peripheral figures from the Mahabharata exemplifies an ethical shift that is modern in spirit: attention to the uncelebrated and to the estranged. At the same time, the gravitas and restraint of his pictorial tone link him to the contemplative nodes within Indian artistic traditions.

An often-noted aspect of his approach is his temperament as a maker. He was reclusive and introverted, and he placed artistic integrity above public performance or commercial acceleration. That stance registers within the paintings: they refuse to perform spectacle, they do not coerce the gaze, and they sustain an internal measure of care in drawing and tonality that is more akin to listening than to declaring. His art, in this sense, invites slow looking and repeated visits; it is cumulative in the impressions it leaves, and it reserves its final meanings for the patient viewer.

Critical Reception & Influence

Critical discourse has placed Pyne among the leading figures of the Bengal School’s legacy and of Indian modernism at large. Reviewers and scholars have emphasized his ability to fashion a unique modernist idiom that remains deeply rooted in Bengali cultural memory while facing squarely the anxieties and metaphysical questions of the twentieth century. His technical mastery of tempera and chiaroscuro has been singled out as a vehicle for emotional and philosophical density, yielding images that resist both anecdote and abstraction and occupy a precise register in between.

The term poetic surrealism has often been applied to his work, not to tether him to a European movement but to suggest the nature of his approach: dreamlike while exacting, fantastical yet ethically pointed. His exploration of the subconscious and of melancholia, and his sustained return to themes of death, memory, and solitude, have been seen as key contributions to a strand of modern Indian art sometimes characterized as bearing a Bengali Gothic sensibility. This atmosphere—somber, layered, inward—has been read not as nostalgia but as an analytic of psyche and history shaped by the specific experiences of Kolkata and of the artist’s own life.

Recognition came from multiple quarters. In the 1970s, he was named by M. F. Husain as the best painter in India, a statement that reflects the esteem he commanded among peers. A documentary engagement with his work led to A Painter of Eloquent Silence, directed by Buddhadeb Dasgupta, which received the National Film Award for Best Arts Film in 1998. Later, the Government of Kerala honored him with the Raja Ravi Varma Award in 2011, and the Indian Chamber of Commerce conferred a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012. These recognitions intersect with a robust exhibition record and with the entrance of his works into significant collections and auctions, keeping his achievements in active circulation.

Pyne’s influence on subsequent generations of artists in India is both thematic and methodological. Many have drawn from his example of integrating myth and folklore with contemporary concerns without falling into illustration, of maintaining rigor in craft while allowing for the open-endedness of symbol and allegory, and of sustaining a studio-based discipline that privileges depth over immediacy. His art continues to be studied and exhibited internationally, sustaining dialogue across cultural contexts about how local narratives and sensibilities can assume modern forms that resonate globally.

The scholarship on Pyne, while substantial, also identifies areas that would benefit from further research. Specific details concerning his animation work at Mandar Studios and the status of surviving materials from that period require fuller documentation. A comprehensive catalogue raisonné of his oeuvre remains a desideratum, especially to clarify the continuum from early watercolors to late tempera works. Likewise, a more granular exhibition history and a consolidated inventory of awards and honors would assist in situating his career chronologically and institutionally. Finally, access to archival materials—personal correspondence and unpublished writings—would provide deeper insight into his studio philosophy, narrative strategies, and evolving sense of artistic responsibility. As retrospectives and posthumous exhibitions continue to frame his legacy, these scholarly tasks promise to refine our understanding of an artist whose silence speaks with durable force.

Conclusion

Ganesh Pyne’s art articulates a vision where darkness is not merely absence but an active, generative field within which forms emerge, pause, and return as memory. From the corridors of a Kolkata childhood to the layered surfaces of his tempera paintings, he constructed a language that remains attentive to the weight of mortality and to the tenderness of what persists in spite of it. His affiliations with the Bengal School and Indian modernism supply a historical anchorage, but his distinct contribution lies in the poetic clarity with which he reconciled tradition and modernity, myth and experience, allegory and empathy.

Across works such as The Harbour, The Assassin, The Night of the Merchant, Bir Bahadur, Ape and the Flower, and Savitri, he sustained a repertoire of images that invite recognition without foreclosing mystery. The series on the Mahabharata’s peripheral figures exemplifies his ethical and narrative poise: attending to the margins as sites of truth. Exhibitions at home and abroad, a landmark retrospective in Kolkata, and continued institutional interest—evident in shows mounted in the years after his passing—have ensured that his paintings remain in public view and critical debate.

In the evolving history of Indian art, Pyne’s achievement is durable because it is exacting. He fashioned a painterly language fit for silence and for the slow revelation of meaning, demonstrating how modern art in India could be intimate without being private, metaphysical without being evasive, and culturally rooted without being parochial. If the poetics of darkness is his signature, it is because he understood darkness as a condition of seeing: the ground against which light, and the forms it reveals, can take on their full measure of human significance.