Chandannagar: Urban History, Architecture, and the French Legacy on the Hooghly

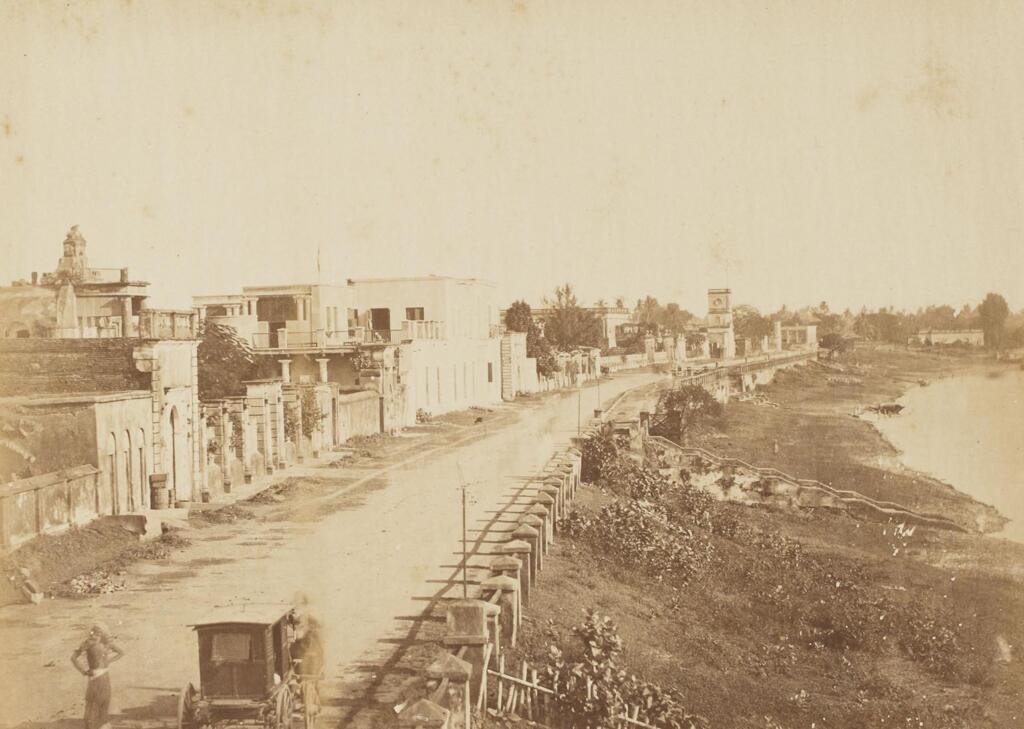

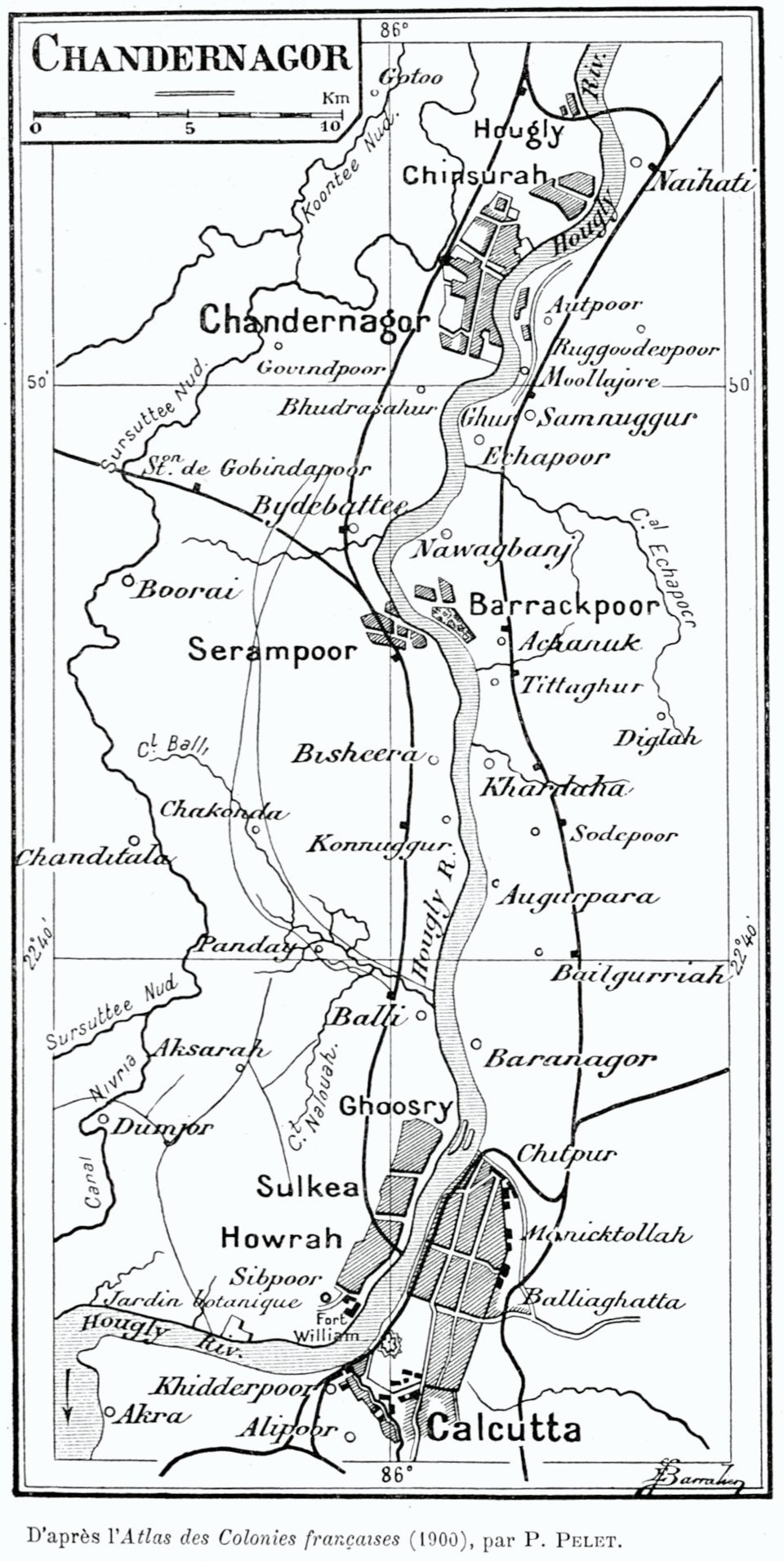

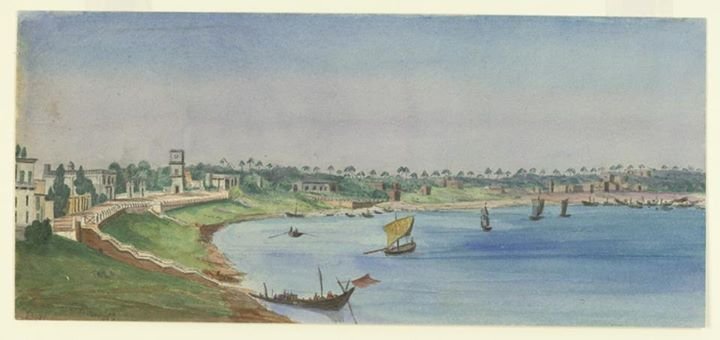

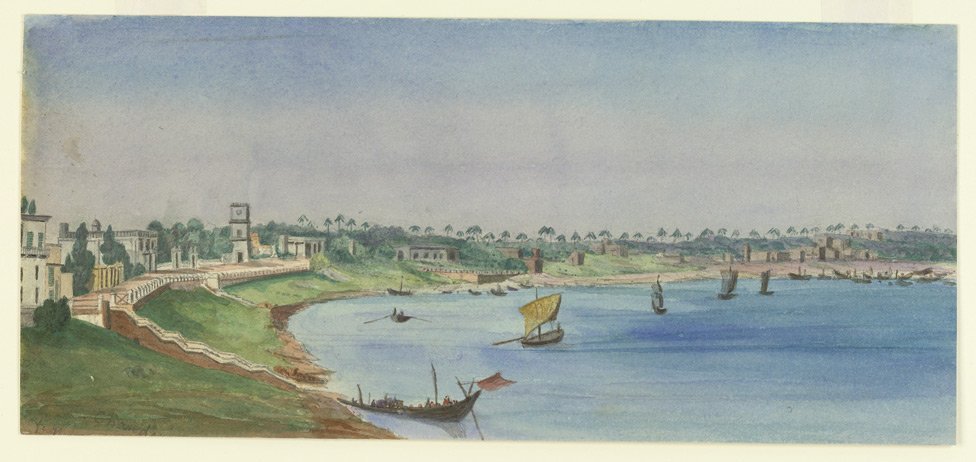

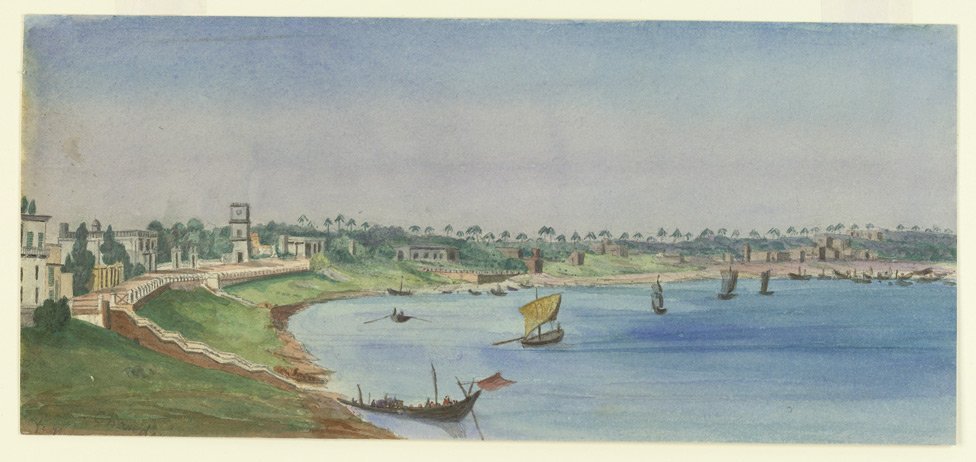

Chandannagar, historically known as Chandernagore, occupies a distinctive place in the urban and cultural landscape of Bengal. Set on the western bank of the Hooghly River in the Hooghly district of West Bengal, India, the city lies within the orbit of the Kolkata Metropolitan Development Authority and serves as the headquarters of the Chandannagar subdivision. Covering approximately 19 square kilometers, with a population of 166,867 recorded in the 2011 Census, Chandannagar is bordered by Chinsurah to the north, Bhadreswar to the south, the Hooghly River to the east, and Dhaniakhali to the west. Its urban form is closely tied to riverine geography and to layered episodes of trade, governance, and cross-cultural exchange. A journey by car or by train from Kolkata takes about an hour, linking this former French settlement to the metropolis while allowing it to retain a singular identity along the river’s tree-lined promenade known as the Strand.

The city’s built environment carries a visible Indo-French imprint: deep verandahs, timber louvers, and brickwork merge with symmetrical facades that speak to colonial design adapted for a humid climate. Public buildings, mansions, religious structures, and mercantile spaces narrate an urban history that unfolded through commerce, conflict, adaptation, and, in more recent times, conservation. Beyond its architectural ensemble, Chandannagar has long stood for a confluence of French and Bengali cultures, expressed in education, social reform, and a vibrant festival calendar. Together, these elements form a coherent urban heritage: a French trading post that grew into a major European commercial center in Bengal, and later settled into the rhythm of a quieter riverside town with enduring cultural memory.

Historical Background

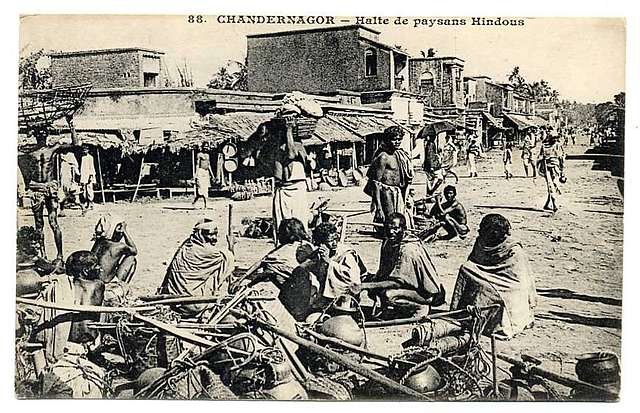

Chandannagar emerged at a time when European trading companies maintained posts along the Hooghly River, pivotal in the movement of goods and ideas through Bengal. In 1673, the French East India Company secured permission from Mughal authorities to establish a trading post here, and by 1688 it had become a permanent French settlement. Its strategic location on the river provided ready access to inland markets and the sea, linking local agricultural and artisanal production with global commercial circuits. The early eighteenth century saw a period of growth, when the French administrator Joseph François Dupleix oversaw an urban expansion and commercial development that left an enduring physical and cultural imprint. Contemporary accounts point to over two thousand brick houses constructed under his governance, an indication of a settlement that was consolidating from a trading enclave into a working town with civic patterns of its own.

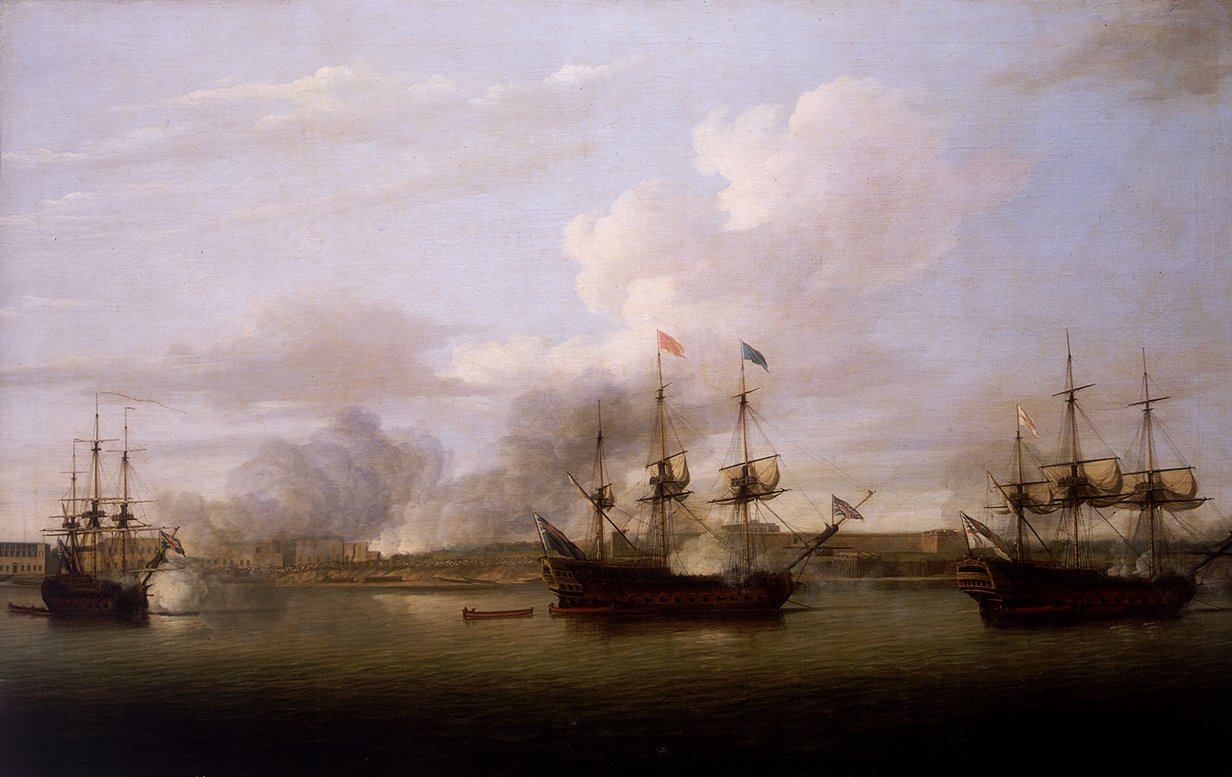

During this same period, Chandannagar became a major European commercial center in Bengal, frequently compared with Calcutta for the scale of its prosperity and reach. Its success rested on maritime trade, the circulation of textiles and other commodities, and the administrative framework that enabled it to function as a thin yet resilient layer of French authority within a complex local milieu. The town’s fortunes were tied to broader Anglo-French conflicts in South Asia and Europe, a contingency that repeatedly reconfigured its governance. Captured by the British in 1757 and returned to French control in 1763, it was taken again by the British in 1794 and restored to France in 1816. These cycles of conflict and restitution bracketed the city’s peak commercial influence, and while they did not erase the urban grid, they recalibrated Chandannagar’s role within a changing colonial geography.

The nineteenth century consolidated Chandannagar’s identity as a French colony along the Hooghly. Through its riverfront civic spaces, religious institutions, and administrative compounds, the settlement continued to hold a certain cosmopolitan character. Over time, as commercial hubs reorganized and infrastructure networks connected larger cities more tightly, Chandannagar’s relative importance diminished. By the early twentieth century, it had become a quieter suburb of Calcutta, a transition that nonetheless preserved key layers of its built heritage. The mid-twentieth century brought decolonization and new national boundaries. Chandannagar’s de facto transfer to India took place in 1951, followed by formal integration into West Bengal in 1954. The longue durée of its history is legible in an urban palimpsest: from a Mughal-era permission to a French trading platform; from periods of conflict and reconstitution to modern incorporation into a metropolitan region—all inscribed along a river that has always been central to Bengal’s urban imagination.

Architecture & Design

Chandannagar’s architectural character is defined by a distinctive Indo-French colonial style adapted to climate, materials, and social life. While the French colonial palette is evident in symmetrical facades, axial compositions, and the use of classical elements such as columns and arched openings, the city’s buildings also incorporate vernacular solutions suited to heavy rains and hot summers. Deep verandahs temper the sun and provide interstitial space between street and interior, while timber louvers enable air movement and privacy. Brick construction, often with lime-based finishes, underscores a material continuity in Bengal, here directed toward an aesthetic that reconciles European planning ideals with the demands of the deltaic environment.

The city’s urban layout, marked by an iron grid plan, frames a sequence of streets leading to the Hooghly River. At the river’s edge, the Strand promenade—approximately 700 meters in length—organizes movement, views, and social gathering. This tree-lined walkway is flanked by colonial mansions and public buildings, creating a coherent frontage that balances civic presence with domestic scale. The Strand’s spatial logic rests on adjacency to water, a feature that enhances the interplay of breezes, shade, and light, and that situates Chandannagar’s architecture in a dialogue with the river’s seasonal rhythms.

Among key heritage structures, the Duplex Palace—now the Institut de Chandernagor—evokes the administrative and residential phase of the French period. Built in the mid-eighteenth century as the residence of Governor Joseph François Dupleix, the building crystallizes the adaptive sensibility of the city’s architecture. A symmetrical layout and a grand portico with columns announce civic authority, while large arched windows and a central courtyard support ventilation and circulation befitting the climate. The use of a courtyard typology aligns with long-standing South Asian traditions, even as the building’s facade language reflects European conventions. The palace’s adaptive reuse as a museum extends its life as a public institution, ensuring that its historical function as a seat of governance transforms into an educational and cultural resource.

Nearby, the remains of Fort d’Orléans speak to the military dimension of European enclaves along the Hooghly in the late seventeenth century. Although now largely in ruins, the fort’s origins as a defensive structure locate Chandannagar within a network of fortified settlements designed to protect trade and maintain a geopolitical balance among competing European powers. The persistence of these ruins functions less as a picturesque backdrop than as an infrastructural memory of an era when control of riverine passages was integral to commerce and statecraft.

The Sacred Heart Church provides a contrasting lens on the colonial built environment through religion and community. Built between 1875 and 1884, and designed by the architect Jacques Duchatz, the church is an example of French Gothic Revival. Its architectural features—pointed arches, stained glass windows, a Latin cross plan, domes, vaults, and flying buttresses—create a richly articulated interior and exterior, tying the parish to a lineage of European ecclesiastical design while anchoring it in a Bengali river town. The structure’s spatial organization demonstrates how imported stylistic vocabularies were calibrated to local context, producing a building that assumes a clear civic presence without overwhelming the surrounding scale.

Secular civic infrastructure also characterizes the Strand. The Clock Tower and Jail, constructed in 1880, present a vertical marker in the urban silhouette. A tall clock tower rises above a single-storey arched base, a composition that integrates timekeeping as a public utility within a pragmatic administrative compound. The current use of the building as a police station reflects a continuity of civic function even as the specific bureaucratic roles have changed. In this respect, the Clock Tower’s endurance embodies the notion of urban adaptability: structures designed for one period’s needs can meaningfully serve another’s, without erasing the memory inscribed in their forms.

Equally resonant is the Nandadulal Temple, built in 1740 in the vernacular Bengali Do Chala style. With its characteristic roof profile and terracotta sculptures, the temple offers an indigenous counterpoint to colonial architecture while belonging fully to the city’s shared heritage landscape. The terracotta work signals the craftsmanship and iconographic traditions of Bengal, here maintained in tandem with the emergence of a European mercantile town. Through this co-presence, Chandannagar reveals a layered urbanity where religious practice, artisanal skill, and cross-cultural encounters found spatial expression.

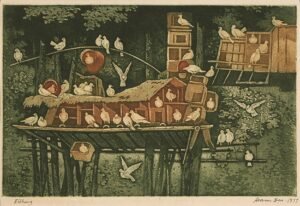

The Patal Bari, or Underground House, adds a note of architectural singularity to the riverside repertoire. Partly submerged below ground level, it has been noted as a resting place for sailors and, over time, acquired cultural visibility through visits by figures such as Rabindranath Tagore and Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar. Its riverside positioning and subterranean elements underline a pragmatic engagement with climate and hydrology as well as a social connection to the rhythms of river traffic. This makes Patal Bari both a curiosity in form and a document of the everyday life of a river city.

The French Cemetery in Chandannagar, housing approximately 150 tombs, extends the architectural narrative into the realm of memorialization. The presence of graves of notable French colonial figures maps the town’s administrative and social history onto a quiet landscape of stone and inscription. Cemeteries often serve as archival spaces in material form, offering dates, names, and epigraphs that, taken together, contribute to an understanding of the people and institutions that shaped the city. In Chandannagar, this funerary landscape complements the palaces, churches, and domestic buildings, reminding visitors that urban heritage includes the architectures of life and of remembrance.

Across these buildings and spaces, certain design themes recur: climate-responsive verandahs, shaded thresholds, and courtyards; symmetrical facades that address streets or the river; the use of brick as a primary material; and the careful positioning of public structures along the Strand. These elements, combined with an orderly urban grid and the constant presence of the Hooghly, lend Chandannagar its distinct architectural identity. The result is an urban ensemble where colonial imprints coexist with Bengali architectural traditions, producing a cityscape of cohesion rather than contradiction.

Social Context & Cultural Memory

From its inception as a French trading post, Chandannagar developed as a site of cultural confluence. The city provided a setting in which European administrative structures encountered Bengali society, not only in the transactional sphere but in education, civic life, and social organization. Over the long nineteenth century, Chandannagar contributed to what has been described as an educational awakening, with institutions, ideas, and practices that emphasized learning and civic participation. These shifts intersected with movements related to the emancipation of women and the spread of democratic ideals inspired by French principles of “Liberté, égalité, fraternité,” which, even when aspirational, furnished a vocabulary for public life. While political interpretations vary, the cultural influence is discernible in the city’s patterns of association, conversation, and civic governance.

Festivals provide a window into how heritage is lived rather than merely preserved. The Jagaddhatri Puja, one of Chandannagar’s most prominent cultural events, is known for its large idols and elaborate lighting displays. These aspects merge artisanal skill with a shared ritual calendar, generating a citywide texture of processions, installations, and visual narratives. Such practices underscore how the public realm—especially the Strand and adjoining streets—functions as a cultural stage. Over time, festival iconography and lighting have also become markers of local identity that coexist comfortably with the colonial-era architecture skirting the river.

Local tastes and crafts deepen this cultural profile. Chandannagar is known for traditional sweets such as the Jolbhora Talsash Sondesh, a delicacy that links culinary art to place. Historic handloom traditions, including dhoti production, connect the city to regional economies of weaving and textile trade, which were integral to the growth of European commercial centers in Bengal. The presence of educational institutions such as Chandannagar College, formerly Collège Dupleix, reaffirms an academic lineage that has shaped generations. The city’s association with notable personalities in revolutionary politics, arts, education, and sports suggests a social milieu that has been both locally rooted and outward looking.

Individual buildings also serve as repositories of memory. Patal Bari’s association with figures like Rabindranath Tagore and Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar confers on it a literary and reformist aura that transcends its architectural novelty. The Sacred Heart Church’s Gothic Revival silhouette stands as a symbol of community for residents and visitors alike. The French Cemetery, for its part, preserves the names of administrators, traders, and families who contributed to the town’s narrative. Taken together, these sites foster a civic memory that is multisensory—experienced in festivals and sweets, in the cadence of the river, and in the gentle shade of verandahs along the Strand.

Visiting / Access Information

Chandannagar is well connected to Kolkata by road, rail, and river. By road, it lies approximately 37 kilometers from Kolkata along the Grand Trunk Road. Local trains from Howrah station on the Howrah–Bardhaman main line provide regular rail access, a convenient option for day visitors. Ferry services on the Hooghly, operated by the West Bengal Surface Transport Corporation, add a riverine dimension to travel and recall the town’s historical links to maritime movement. The nearest airport is Kolkata Airport, about 40 kilometers away, offering domestic and international connectivity.

The riverfront Strand promenade offers a tree-lined walkway with views of the Hooghly and a sequence of colonial-era buildings. The Chandannagar Museum, housed in the Institut de Chandernagor, presents aspects of the city’s heritage; listed visiting hours are 11 AM to 5:30 PM, closed on Thursdays and Saturdays, with an entry fee of Rs. 5 for Indian visitors and Rs. 20 for foreign nationals. The Sacred Heart Church remains open for regular services and visits, reflecting its role as both a heritage site and an active place of worship. Other notable sites include the French Cemetery, Patal Bari, and the Nandadulal Temple, each contributing a different dimension to the city’s historical fabric.

Beyond architecture, Chandannagar’s cultural calendar, especially the Jagaddhatri Puja, draws visitors interested in festival traditions marked by large idols and elaborate lighting displays. The city’s recreational amenities include parks such as KMDA Park and Mango Gardens, and its neighborhoods reflect a blend of heritage streetscapes and contemporary urban life. Together, these elements allow for a layered visitor experience that encompasses the riverscape, historic buildings, living religious sites, and the rhythms of a modern Bengali town with a French legacy.

Conclusion

Chandannagar’s significance lies in the coherence of its urban story and the legibility of that story in its built environment. The city’s emergence as a French trading post in 1673, consolidation as a permanent settlement by 1688, and expansion under Dupleix frame an architectural and urban narrative grounded in maritime commerce and administrative ambition. Its distinctive Indo-French colonial style—deep verandahs, timber louvers, brick facades, and careful symmetry—adapts European design to local climate and craft. The Strand promenade stitches together this heritage along the Hooghly, presenting a civic front where palaces, churches, and public buildings converse across time.

As an urban organism, Chandannagar has demonstrated remarkable adaptability. Following cycles of Anglo-French conflict and changing economic fortunes, it evolved from a major European commercial center into a quieter suburb of Calcutta by the early twentieth century. Many colonial-era buildings have transitioned to new uses, such as the Duplex Palace’s conversion into a museum and the functional continuity of the Clock Tower building as a police station. Simultaneously, religious structures like the Nandadulal Temple and the Sacred Heart Church continue to shape social life, while the French Cemetery endures as a site of remembrance.

The conservation landscape is, however, complex. A number of historic structures require restoration, and private heritage properties often face challenges ranging from multiple ownership to financial constraints and maintenance issues. Urbanization and real estate pressures have led to the demolition of some historic buildings and their replacement with modern apartments and commercial complexes, contributing to a gradual thinning of the heritage fabric. Efforts have been made to protect certain sites—such as the recognition of the Sacred Heart Church by the West Bengal Heritage Commission—and to adapt notable buildings for new uses, including the Institut de Chandernagor. A participatory conservation approach that involves local stakeholders alongside government institutions remains key to sustaining Chandannagar’s architectural and cultural heritage.

In its architecture, festivals, and everyday practices, Chandannagar offers a measured and instructive example of how colonial-era cities in India have navigated change. The city’s French legacy in Bengal is not a closed chapter; it is an active layer in the lived experience of residents and visitors, articulated in the hum of trains from Howrah, the steady drift of boats on the Hooghly, the lighting displays of Jagaddhatri Puja, and the shadows cast by colonnades along the Strand. Preserving this heritage—material and intangible—ensures that Chandannagar continues to function as an urban archive: a place where the past is accessible, the present is engaged, and the future can be planned with sensitivity to the values encoded in brick, stone, timber, and river light.

One Response