Brihadeeswara Temple, Thanjavur: Chola Architecture and the Grammar of Sacred Geometry

On the southern bank of the Kaveri River stands the Brihadeeswara Temple of Thanjavur, a granite colossus that has shaped the vocabulary of Dravidian temple architecture for over a thousand years. Also known as Brihadisvara, Rajarajesvaram, Peruvudaiyar Kovil, and Thanjai Periya Kovil, this Shaivite complex is a defining example of how sacred geometry, engineering innovation, and imperial vision converged in the early eleventh century. Recognized within the UNESCO World Heritage listing of the Great Living Chola Temples, the site continues to function as a living shrine while serving as a benchmark for scholars studying South Indian architecture, iconography, and cultural history.

Situated approximately 350 kilometers southwest of Chennai, the temple complex extends across about 18 hectares within fortified enclosures that have evolved over time, with an additional buffer zone of 9.58 hectares. Within this monumental precinct, the soaring 13-tiered vimana, the axial halls, the giant Nandi, and the richly carved walls establish a careful dialogue of mass and proportion. The result is both a spatial pilgrimage and a lesson in structural clarity. Whether approached as a case study in premodern engineering or as a classical expression of Tamil art and ritual, the Brihadeeswara Temple offers a coherent architectural cosmos—ordered by mandala grids, encoded with theological meaning, and activated by daily worship.

The temple’s endurance is inseparable from its material and intellectual fabric. Built entirely of granite with precise stone-cutting and interlocking techniques that avoid mortar, it manifests an architectural intelligence attentive to stress, resonance, and longevity. The design embraces Vastu Shastra and the vastu-purusha-mandala, arranging sacred space through axial symmetries and calibrated proportions that connect earthly ritual to cosmological order. In doing so, Brihadeeswara continues to be read as both a historical monument and a working manuscript of sacred geometry.

Historical Background

Brihadeeswara Temple was commissioned by the Chola emperor Rajaraja I and constructed between 1003 and 1010 CE, during a period of exceptional political consolidation and cultural patronage. Rajaraja’s reign (985–1014 CE) marks a high watermark of Chola statecraft, maritime ambition, and artistic production. The temple originally bore the name Rajarajesvaram, directly linking the royal patron to the divine overlordship of Shiva. Over time, the temple came to be known as Brihadeeswara, the Great Lord, a title that echoed its vast scale and spiritual prominence.

The construction timeline—approximately seven years—remains remarkable given the magnitude of the project and the technological constraints of the era. The temple’s realization in such a span suggests an organized workforce, extensive quarrying and transport networks, and a governing vision that fused devotional intent with state symbolism. Inscriptions at the site, authored by Rajaraja I and his successors, help clarify the administrative scaffolding that supported the temple’s activities, from endowments and land revenue to staffing of priests, dancers, and musicians.

In the centuries following the Chola period, the temple continued to receive care and additions under different ruling powers. The Pandyas, the Delhi Sultanate, the Vijayanagara Empire, the Madurai Nayaks, and the Marathas each played roles in maintenance, renovation, and occasional extension. These layers of stewardship document the building’s enduring importance as a sacred center and a regional landmark. In 1987, the temple was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list as part of the Great Living Chola Temples, together with the temple at Gangaikondacholapuram and the Airavatesvara Temple at Darasuram, affirming its standing as a monument of outstanding universal value.

While some traditions attribute design authorship to master architects associated with the Chola court, including Kunjara Mallan Raja Rama Perunthachan, specific details about the original architects require further corroboration. What is clear is that the temple’s design reflects a formal grammar honed by generations of South Indian builders, here brought to a compelling climax under Rajaraja’s patronage.

Architecture & Layout

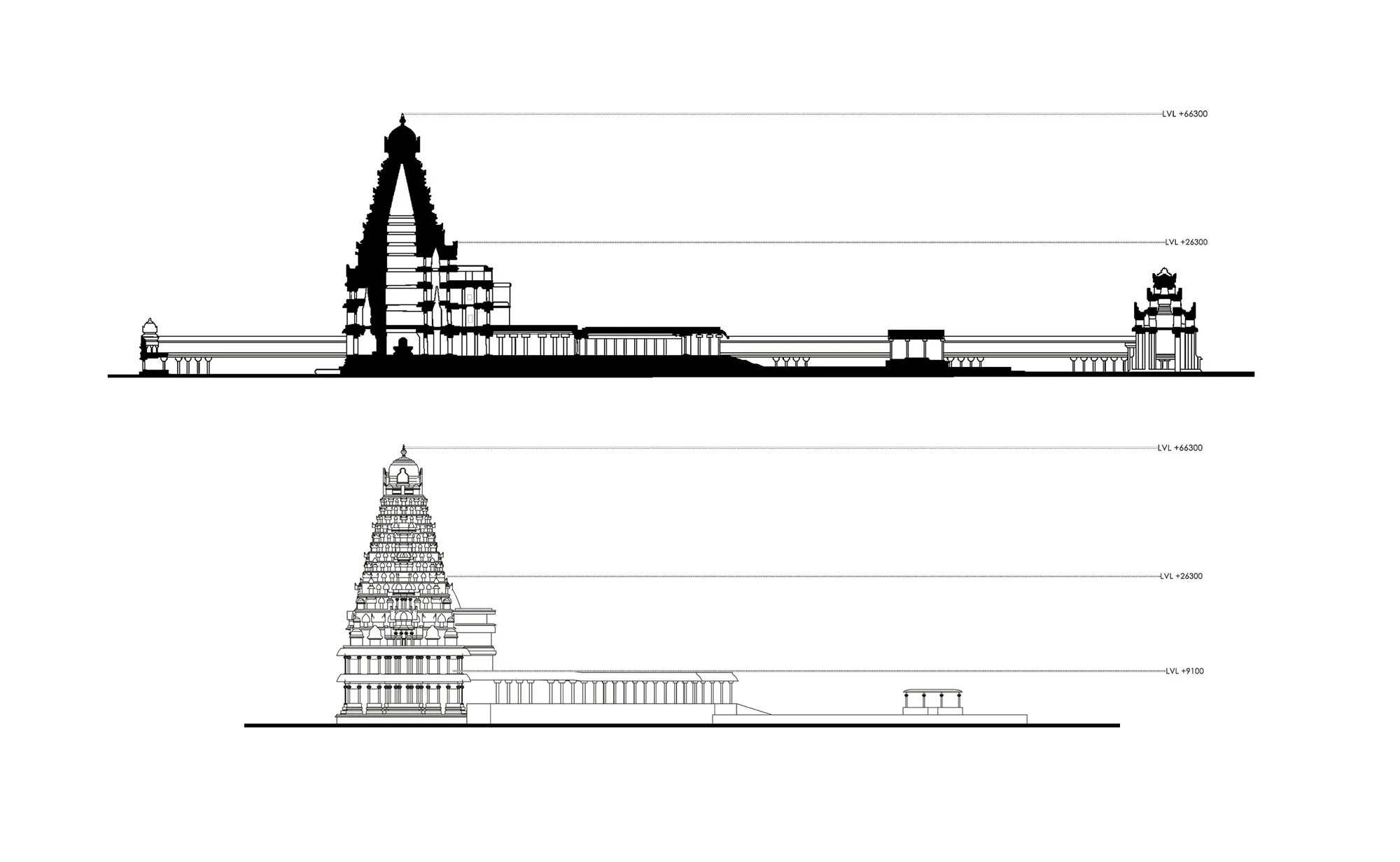

Brihadeeswara exemplifies the Dravidian mode: a square sanctum crowned by a pyramidal tower (vimana), axial halls aligned to the principal east–west axis, and an enclosure whose walls and gateways structure movement from the profane exterior to the sanctified core. The plan is rectangular, measuring roughly 240.79 meters along the east–west axis and 121.92 meters north–south. This compound is nested within concentric prakarams, their massive walls punctuated by gopurams that frame the processional routes and regulate the visitor’s approach.

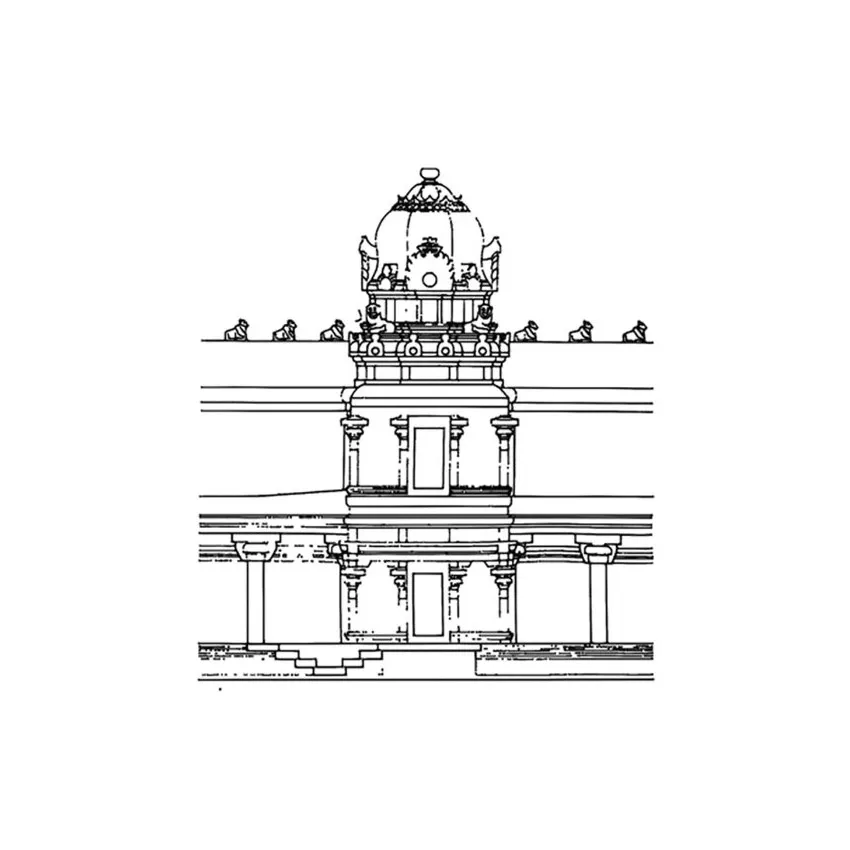

The temple’s most recognizable feature is its 13-tiered vimana, rising to approximately 66 meters (216 feet). The tower’s base is a square with sides of about 99 feet, and its profile is a regular tapering pyramid rather than a curvilinear form. This linearity offers a clear distinction from later Chola constructions such as Gangaikondacholapuram, where the superstructure evolves toward a more sinuous silhouette. The Brihadeeswara vimana culminates in a massive granite cupola (kumbam) estimated at around 80 tons. Traditional accounts and structural reasoning suggest the cupola was raised by a lengthy earthen ramp, extending approximately 6.44 kilometers, enabling a controlled haul to the summit.

From foundation to finial, the temple is executed in granite, a stone sourced from quarries more than 60 kilometers away. Over 130,000 tons are believed to have been employed. The construction uses interlocking blocks and corbelled techniques that obviate the need for mortar, an approach that requires precise cutting and exact load paths. This method, combined with a carefully engineered raised platform, has proven resilient, with the structure having withstood seismic events and environmental pressures across the centuries.

The sanctum sanctorum (garbhagriha) hosts one of the largest Shiva lingams in India, measuring approximately 12 to 13 feet in height. The axial sequence of halls—the antrala connecting vestibule, the maha-mandapa as the great gathering hall, and the mukha-mandapa as the principal community space—establishes a ceremonial continuum that aligns the devotee’s movement to ritual milestones. Each space intensifies the approach to the sanctum, narrowing visual focus and acoustic resonance in a manner synchronized with liturgical rhythms.

Facing the sanctum is the immense Nandi, Shiva’s bull vehicle, carved from a single block of granite and measuring about 6 meters in length and 3.7 meters in height. The Nandi’s placement reinvigorates the axis, guiding sightlines and structuring the temple’s spatial narrative while embodying guardianship and devotion. Within the broader precinct, subsidiary shrines provide a ritual ecology around the main sanctum, extending worship to deities including Vishnu, Subrahmanya (Murugan), Ganesha, Parvati, and guardian deities aligned to the directions.

The mathematics of the temple is as central as its masonry. The layout follows Vastu Shastra and the vastu-purusha-mandala, encoding the building within a diagram that balances cardinal orientation, modular measure, and symbolic placement. Archaeological surveys and architectural analyses have identified the use of precise geometric constructs, including 3-4-5 right triangles, to regulate alignments and proportions. This geometric discipline is visible in the strict axiality, the modular stacking of the vimana’s tiers, and the coordination of wall, plinth, and tower profiles. The temple’s proportions present a scaled mandala in stone, translating cosmic diagrams into inhabitable architecture.

Among the enduring points of inquiry is the claim that the vimana casts no shadow at noon during the equinoxes. While this observation has become part of the temple’s popular lore and is referenced in some studies, it warrants careful astronomical verification due to variables of latitude, tower geometry, and seasonal solar angles. Such questions underscore the temple’s layered rapport with science, inviting ongoing research at the intersection of architecture and astronomy.

Sculpture, Inscriptions & Iconography

The sculptural program of Brihadeeswara is expansive yet precisely integrated into the architecture. On the vimana’s exterior, niches and pilasters articulate the vertical rise, while miniature shrines—kutas and salas—rhythmically populate each tier. The iconographic repertoire is rich: forms of Shiva such as Bhikshatana, Virabhadra, Kalantaka, Natesa, Ardhanarisvara, and the Alingana motifs appear alongside Durga, Lakshmi, Sarasvati, and other deities. These images mediate narratives of power, protection, and cosmic balance, inflecting the architectural mass with theological detail.

One of the temple’s significant contributions to the arts lies in its depiction of dance. Carved into the upper-storey corridor walls are representations of 81 of the 108 Bharatanatyam karanas described in the Natya Shastra. This sculpted anthology testifies to the Chola court’s patronage of classical performance traditions and documents the transmission of movement grammar into stone. The presence of musicians and dancers in the administrative inscriptions complements the sculptural evidence, suggesting an integrated ecosystem of ritual, music, and dance.

The inner ambulatory zones preserve fragments of murals and frescoes that range across sectarian and narrative themes. Shaivism remains central, but Vaishnavism and Shaktism are also represented, together with scenes from mythic cycles and glimpses of Chola court life. Many of the original Chola-period paintings are partially overlaid by later Nayaka-era works, a palimpsest that complicates attempts to reconstruct the initial iconographic program. Conservation efforts have sought to stabilize these surfaces, but the precise extent and condition of the earliest layers still invite detailed study.

Inscriptions constitute an archive within the temple. Executed in Tamil and Grantha scripts, these records provide a granular picture of endowments, donations of gold, silver, and precious stones, land grants, and provisions for temple functionaries. They document the roles of priests, dancers, musicians, and artisans, portraying the temple as both a spiritual institution and a managed civic enterprise. Through these epigraphs, the economic life of the monument becomes legible, connecting ritual obligations to agrarian revenues and guild labor.

Archaeological surveys further illuminate the technical foundation of the complex. The use of interlocking granite blocks and corbelled vaulting without mortar speaks to precise engineering and skilled workmanship. Measurements and alignments suggest a rigorous application of geometric reasoning to the ground plan and elevation alike. The raised granite platform and load-bearing strategies have allowed the temple’s core structures to endure seismic activity and environmental stress. Restoration by the Archaeological Survey of India has helped preserve murals and structural integrity, while documentation by later regimes such as the Nayaks and Marathas records additions that now form part of the site’s historical stratigraphy. Several areas remain active fields of research, including the exact mechanics of hoisting the 80-ton cupola, the acoustic properties of interior spaces, and the comprehensive cataloging of damaged or missing inscriptions.

Cultural Significance

Brihadeeswara Temple functions as a living religious center dedicated to Lord Shiva, sustaining continuous worship practices for over a millennium. While Shaivism provides the core devotional framework, the presence of shrines to Vishnu, Parvati, Murugan, Ganesha, and guardian deities illustrates an inclusive sacred landscape in which multiple traditions coexist. The massive Shiva lingam and the monumental Nandi convey a sense of presence and guardianship that anchors both individual devotion and communal ritual.

As a major pilgrimage and cultural site, the temple also fosters the classical arts. Annual observances such as Maha Shivaratri draw large congregations, while dance festivals, including the Brahan Natyanjali, affirm the ongoing relationship between performance and the sacred environment. In this sense, the temple not only conserves the past but actively produces living traditions, enabling continuity of forms codified in both sculpture and scripture.

Beyond the liturgical sphere, the temple symbolizes the zenith of Chola artistry and statecraft. Its conception, realized in stone and governed by sacred geometry, asserts an order where political authority, religious devotion, and architectural mastery are mutually reinforcing. The site stands as a powerful emblem of Tamil cultural identity and as a reference point for temple design across South India and into Southeast Asia, where Chola influence once extended. As part of the UNESCO-recognized Great Living Chola Temples, Brihadeeswara contributes to global understandings of how monumental architecture can embody both local specificity and universal aspirations toward harmony, proportion, and cosmic orientation.

At its core, the temple’s design encodes a philosophy: that built space can reflect the structure of the cosmos and, through ritual and movement, bring human life into accord with it. This relationship between geometry and devotion continues to inspire architects, artists, and scholars who look to Brihadeeswara for lessons in how form, function, and meaning may be elegantly reconciled.

Visiting / Access Information

Thanjavur is readily accessible by road and rail, with the nearest airport located at Tiruchirappalli, approximately 55 kilometers away. The temple remains open daily, typically from 6:00 AM to 12:30 PM and from 4:00 PM to 8:30 PM. Entry is free. Photography with handheld cameras is generally permitted without fee, while professional photography requires prior permission from the Archaeological Survey of India. The complex is maintained through the collaborative oversight of the Archaeological Survey of India and the Tamil Nadu Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Department.

As a major tourist and pilgrimage destination, the temple has seen upgrades to visitor amenities, including improved lighting and signage. Multiple gopurams offer access points through fortified walls, some of which were added in the sixteenth century and in subsequent periods. Visitors are advised to respect the sanctity of the site, observe local customs, and be mindful that Brihadeeswara is foremost a functioning place of worship, with daily rituals that structure its rhythms and spaces.

Conclusion

The Brihadeeswara Temple at Thanjavur stands as a consummate demonstration of Chola architecture, marrying granite’s intransigence to the fluid logic of sacred geometry. Its 13-tiered vimana, the monumental Nandi, the vast mandapas, and the precise, mortarless masonry attest to an intellectual and technical culture of exceptional refinement. Sculpture and painting translate theological and performative traditions into durable forms, while inscriptions open a window onto the administrative and social systems that sustained this religious enterprise.

As an enduring monument and a living shrine, Brihadeeswara continues to mediate between the temporal and the eternal: a ritual space that remains in daily use, an architectural landmark that anchors regional identity, and a research site that prompts new questions about engineering, iconography, and historical memory. Its place within the Great Living Chola Temples ensures ongoing conservation and study, while its design remains a touchstone for thinking about how architecture can embody cosmic order. In the measured ascent of its vimana and the balance of its plan, the temple offers a timeless lesson in how precision, devotion, and power can be inscribed in stone with clarity and grace.