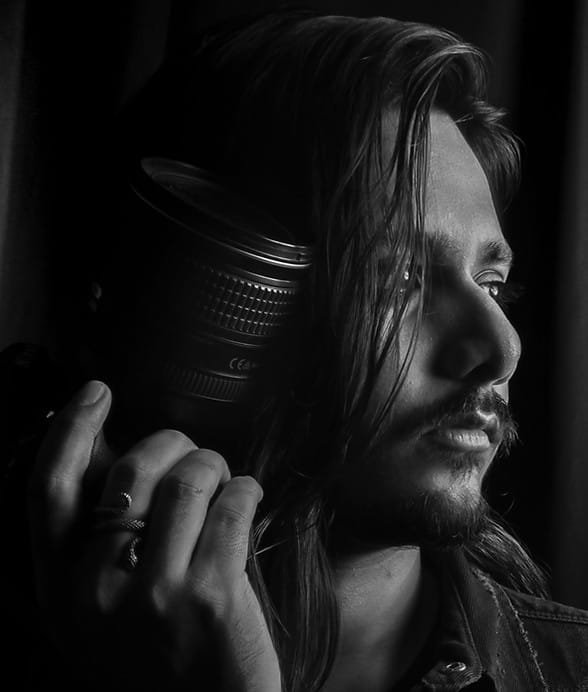

We met over a late lunch on a rainy Sunday afternoon. The 25-year-old Arpan Dutta Chowdhury arrived with a camera strap slung over one shoulder. The rain-streaked window felt like a natural lens, perfect for this conversation. Arpan is originally from Jhargram, and art has always been part of his family. His father worked as a painter and digital artist, so Arpan grew up around colours, compositions, and all manner of art forms. At nineteen, he made the pivotal decision to leave Jhargram for Kolkata to formally pursue photography—a leap of faith that shaped his worldview.

Not long after, he apprenticed and trained under photographers like Sounak Banerjee, Rafique Sayed and attended workshops with Raghu Rai. Those early tutelages, together with his upbringing, explain much about how he works now. “Training under such diverse masters was incredible,” he tells me. “Being around that kind of clarity didn’t just shape my work; it shaped me.”

Naturally, I ask what he learned from Sounak Banerjee, with whom he spent considerable time. Arpan leans back: “The lessons were practical.” From Sounak-sir he learned to keep experimenting, never to be tied to a single “look,” and to treat each photo as a question rather than an answer. “The only way to stay alive as an artist is to keep experimenting,” he says, leaning forward now. “Style is a by-product, not a goal. Experimentation keeps my eyes honest and my ego in check.” The rain keeps working the windows; the weather feels like a good metaphor for the experimental approach he’s describing.

©Arpan Dutta Chowdhury

Alongside the big-picture lessons, he points out a smaller, domestic habit that made a huge difference: punctuality. What feels like a minor discipline in a Kolkata studio turned out to be a survival skill outside. That punctuality, Arpan says, paid off during his stint in Mumbai, which had the tightest city shoots.

The conversation turns to monochrome. I ask how it alters perception and whether black-and-white evokes timelessness or simply abstraction. Arpan’s reply is immediate: removing colour changes everything. Without colour’s pull, the frame stops competing with itself. He quotes Elliott Erwitt: “Colour is descriptive. Black and white is interpretive.” It isn’t only an aesthetic choice; it shows how he thinks visually. When I press him on the “timeless” idea, he is sceptical of nostalgia for its own sake. Yes, black-and-white can detach an image from a particular era—it might look like yesterday or decades past—but that detachment doesn’t make the picture more meaningful. For him, timelessness is a by-product of composition and feeling, not a trick achieved by desaturation.

©Arpan Dutta Chowdhury

He finishes with a practical, slightly impatient piece of advice for those chasing “that” look: don’t flip a colour picture to black-and-white because it’s fashionable. Learn to see in monochrome from the start and let the image ask for it, rather than forcing it.

When I ask about the rise of phone photography, Arpan doesn’t dismiss it, but he is clear about the distinction. “A phone is not a camera first and foremost,” he says. “A phone has a camera.”

The difference matters to him. A phone can make images, yes, but it comes with constraints: you can’t truly adjust aperture or exercise the same control over depth and light. The device decides too much for you. “It’s like reading a physical book versus an e-book,” he explains. A phone also carries a hundred other purposes competing in the background. At the same time, he believes AI and evolving digital tools allow artists to experiment. He urges photographers to see these advancements from an artist’s perspective, not just a technical one. AI-driven tools, he says, have already improved parts of his workflow. With noise reduction and other fixes, he can shoot more freely in low light and save hours in editing—easier to stay focused on making rather than fixing.

©Arpan Dutta Chowdhury

My first cup of tea went cold a while back; by the time the second arrived, I asked the question that had been sitting with me all afternoon: if he could photograph any historical or cultural event, what would it be? He says Partition-era India. Not for the headlines, but the human moments that lived between the politics: kitchens emptied and re-filled, courtyards with belongings, restless railway stations. I nudge the conversation back to his city, asking where in Kolkata he loves to shoot.

©Arpan Dutta Chowdhury

He names the usual Mullick Ghat. On favourite gear, he pulls out one of the lightest zooms he carries, a 28–80mm, and shows it to me. He unzips his bag; there’s the camera—a Nikon D850—ready to shoot.

if he could photograph any historical or cultural event, what would it be? He says Partition-era India.

I’m curious about his work beyond Kolkata. He frequently travels to Mumbai and Bangalore for projects now, so I ask about the different work cultures. He talks about a seven-month stay in Mumbai early in his career, working with Rafique Sayed, and how important it was. “Rafique-sir made me work fast,” he says. “We planned a lot less and made do with whatever was available.” Sayed taught him a kind of commercial spontaneity that formal training did not.

©Arpan Dutta Chowdhury

The lesson has stayed, even as his style evolved. “Now, in my fashion shoots, I don’t use many props,” he says. “The focus remains on emotions. Props are just tools.” Bangalore, he says, has given him some of the most interesting briefs. Mumbai, by contrast, brought scale. He laughs as he sums up the city’s attitude to time:

“If someone is on time, then they’re late.” Everyone shows up early and starts moving.

When I ask about favourite photographers, he names Henri Cartier-Bresson and Helmut Newton, among others. He also admires Sebastião Salgado for his epic black-and-white and humanitarian storytelling. It’s clear Arpan’s approach borrows a little from Salgado’s empathy. When the conversation turns to landscapes, he brings up Ansel Adams. Adams taught him, even from afar, that landscapes aren’t backdrops; they’re characters.

We’ve already been talking about old masters, so we drift to film versus digital. He isn’t anti-digital. The freedom to experiment, to try angles and settings, and to iterate quickly is invaluable. You can shoot endlessly, experiment without fear, and work faster in commercial environments where deadlines are tight. Film, on the other hand, carries a method. It slows you down and forces you to think before clicking. “Everyone should shoot film at least once,” he tells me, “just to know what it feels like when every frame matters.” Film teaches restraint and respect for process, and that respect returns to digital work too. The romance isn’t necessary to be a photographer, but it reminds you why you fell in love with making pictures in the first place.

Arpan packs his gear with the same precision he brings to everything else. The rain has stopped, the city washed. He smiles as we stand to leave and, almost offhand, invites me to join one of his street-photography walks “if you have the time,” and then—warmly, like an instruction—adds, “early morning.” At twenty-five, Arpan practises a photographer’s highest discipline: waiting, so that moments can arrive fully formed in his frames.

India Photo Fest 2025

Largest Photography Exhibition in India · 19–21 Dec · ICCR Kolkata

Apply Now