Nandalal Bose and the Formation of an Indian Modernism

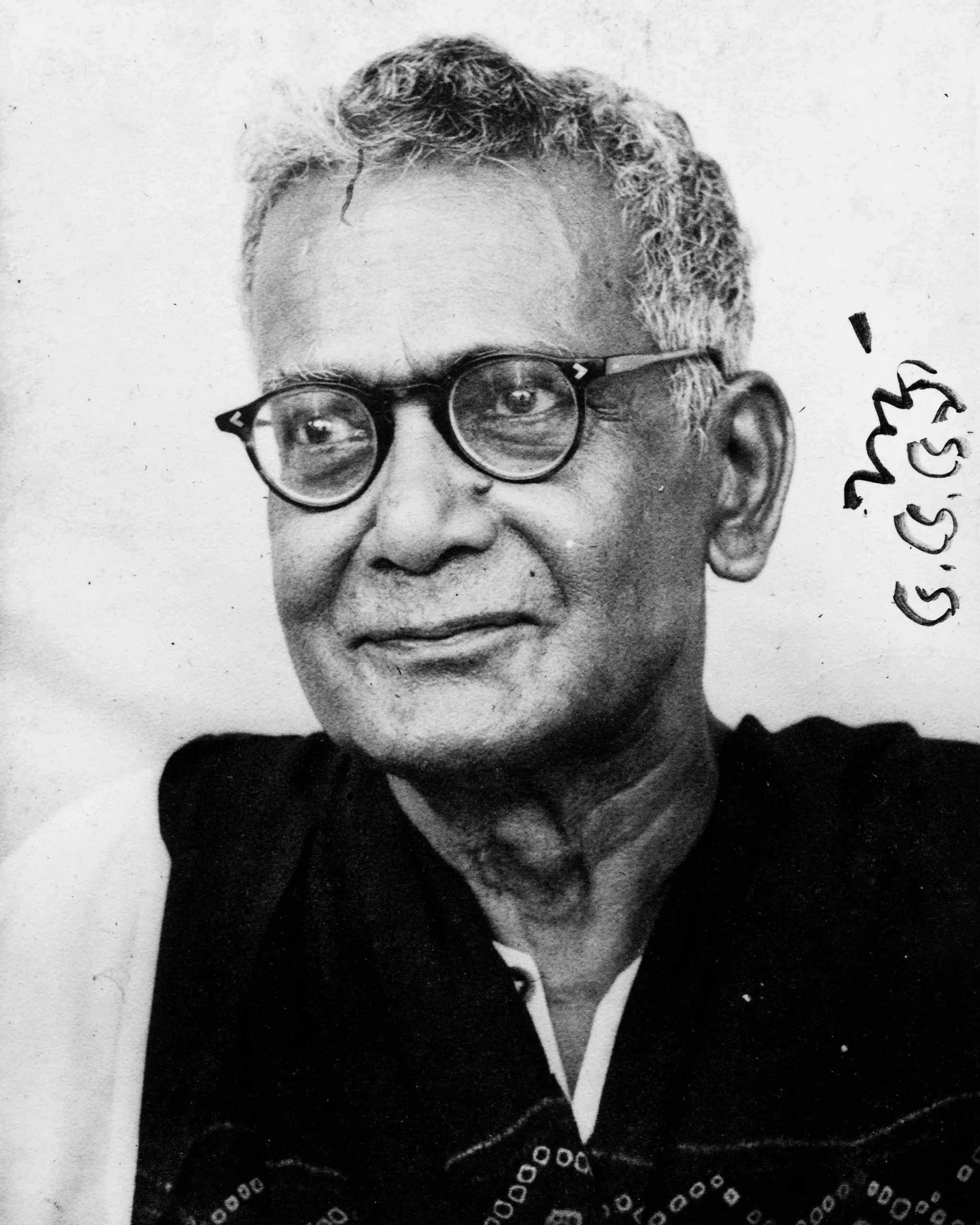

Nandalal Bose (1882–1966) occupies a foundational place in the history of Indian modern art. His work forged a distinctly Indian modernism by integrating classical and folk traditions with a nuanced awareness of global artistic currents. Active from the early to mid-twentieth century, Bose engaged with the intellectual and cultural ferment of his time, particularly the nationalist movement and the artistic renaissance that accompanied it. He aligned closely with developments at Santiniketan, where Contextual Modernism emphasized the reciprocity between artistic freedom, cross-cultural learning, and a rooted engagement with local materials and motifs. The outcome was a modern visual language that did not imitate European paradigms or return to tradition as pastiche, but developed an independent, critically grounded idiom responsive to India’s histories, environments, and social imagination.

This article examines Bose’s contribution to Indian modernism by situating his practice within its historical context, discussing the stylistic and technical features of his art, and reviewing selected works central to his legacy. It also reflects on his pedagogical and institutional influence at Santiniketan, where his mentorship helped shape subsequent generations of artists. Throughout, the analysis underscores how Bose’s experimentation with media, his study of Indian artistic lineages, and his responsiveness to East Asian practices coalesced into a coherent vision of modern art that remained attentive to place, community, and the ethics of making.

Historical Context

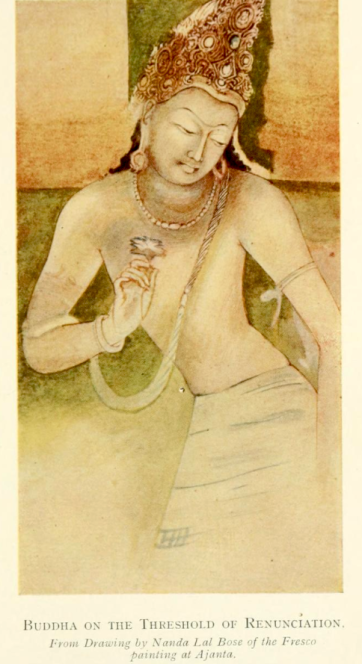

The arc of Nandalal Bose’s career coincided with the rise of Indian nationalism and the Swadeshi movement, moments in which questions of cultural identity were deeply entangled with political self-assertion. Within this matrix, art assumed a strategic role. It could challenge the prestige of colonial aesthetics by retrieving and reframing indigenous traditions, and it could serve as a vehicle for public communication, contributing to the visual vocabulary of collective action. The Bengal School of Art emerged in this climate as a self-conscious alternative to Western academic realism, redirecting attention toward sources such as the Ajanta murals and the legacies of Mughal, Rajput, and Pahari painting, as well as various folk practices. Bose’s early formation in this milieu sustained his lifelong dialogue with Indian art histories while opening paths for modern experimentation that were neither insular nor derivative.

At Santiniketan, where debates around art, education, and society overlapped, Bose’s approach matured into what has been identified as Contextual Modernism. This orientation emphasized the relationship between work and environment, encouraged the assimilation of new techniques through a conversation with local traditions, and cultivated independent thinking across disciplines. As principal of Kala Bhavana, Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, from 1921 to 1951, Bose played an instrumental role in institutionalizing these values. Rather than organizing practice around rigid canons, he nurtured inquiry into materials, craft, and pictorial languages anchored in Indian contexts but open to global methods, notably those from Japanese and broader East Asian art.

His practice and public engagements unfolded alongside the freedom struggle. Collaborations with figures such as Mahatma Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore amplified his art’s cultural and civic presence. Bose’s contributions to Indian National Congress sessions and his work on the original manuscript of the Constitution of India exemplify an artist’s participation in forging shared symbols and narratives during a transformative period. These commitments did not reduce his art to propaganda; rather, they reframed the relation between art and society at a moment when cultural self-fashioning was inseparable from the political horizon.

While the overarching coordinates of Bose’s life and milieu are established, some areas invite further study. The extent of his collaborations with contemporaries in the Bengal School and the broader Contextual Modernism network requires closer archival research, as does a comprehensive cataloguing of his oeuvre and the reception of his work across different regions during his lifetime. Continued inquiry into the range of non-Indian influences beyond the Japanese and East Asian sphere, as well as a detailed reconstruction of his curriculum and methods at Kala Bhavana, would further clarify the reach and specific mechanisms of his influence.

Stylistic Characteristics

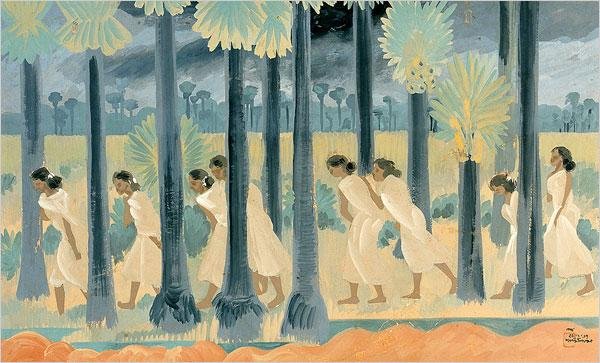

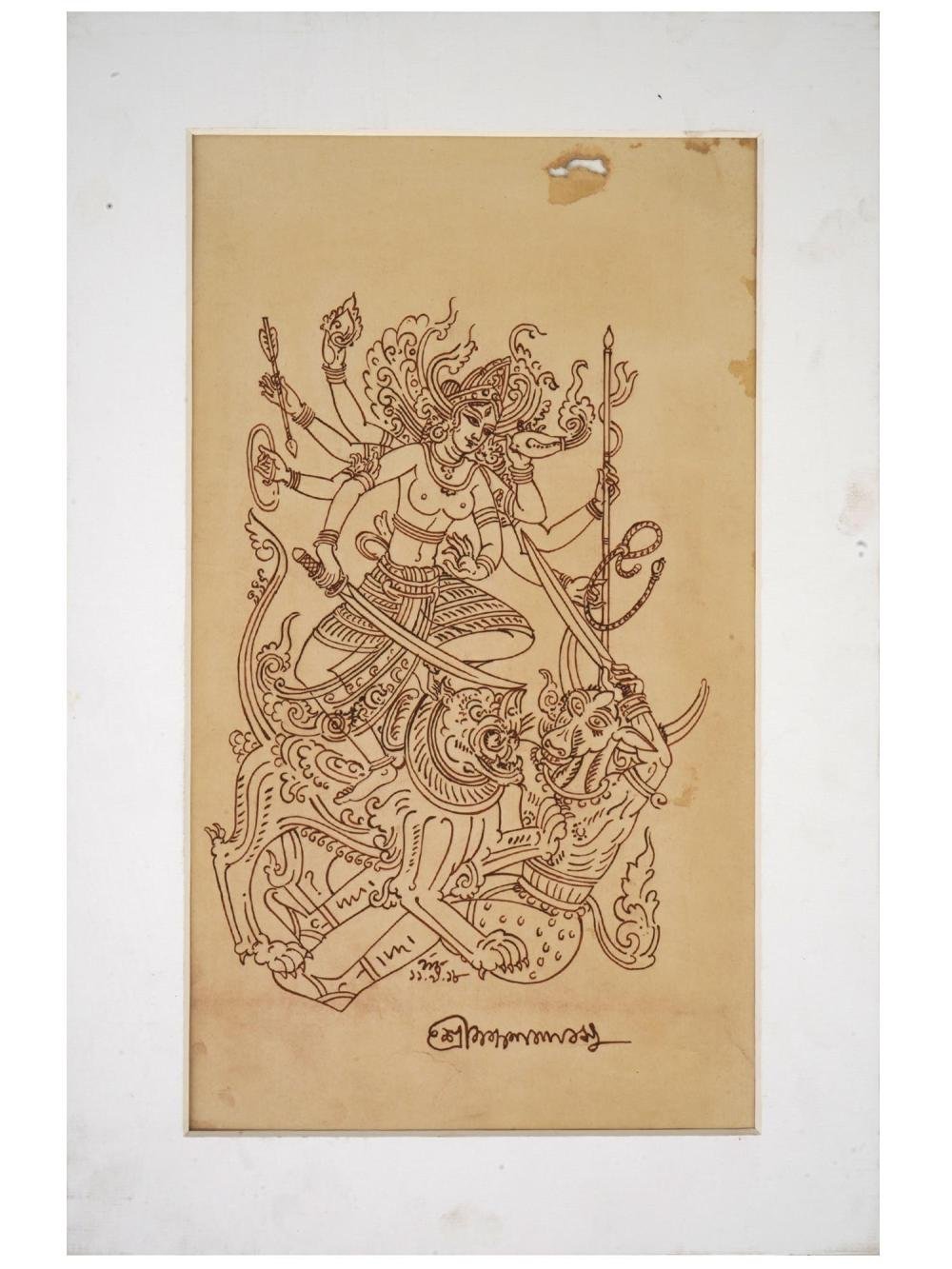

Bose’s most enduring contribution lies in his ability to build a modern pictorial language by synthesizing various Indian art historical sources with contemporary technique. The Ajanta murals, with their rhythmic line, compositional poise, and narrative clarity, furnished one key model. Mughal, Rajput, and Pahari miniatures informed his approach to form, color, and ornament, especially in their refined handling of contour, flattened spatial arrangements, and calibrated palette. Yet his work was not an exercise in replication. Rather, these lineages were translated into a modern grammar that favored economy of means, clarity of structure, and compositional balance attuned to new thematic and social horizons.

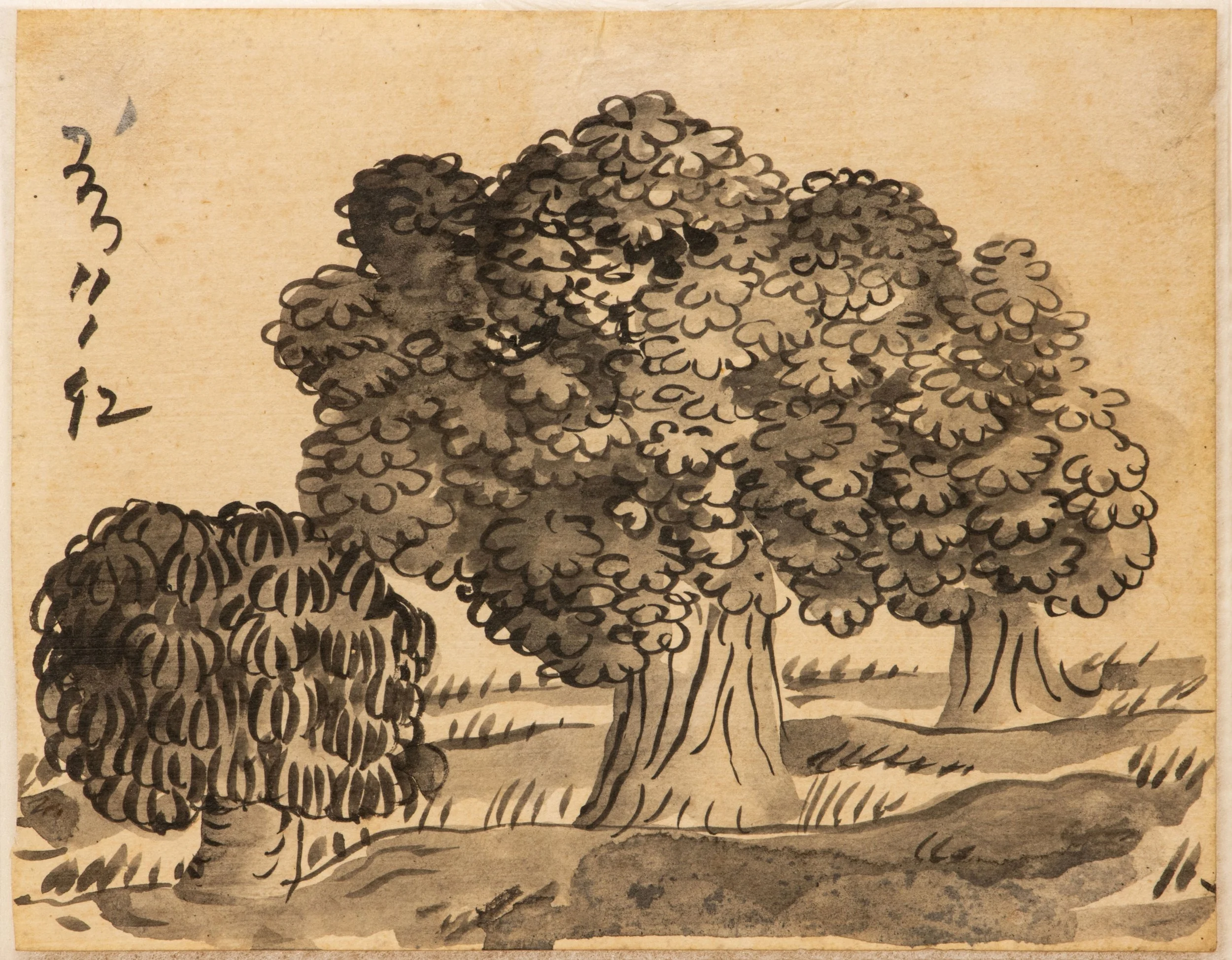

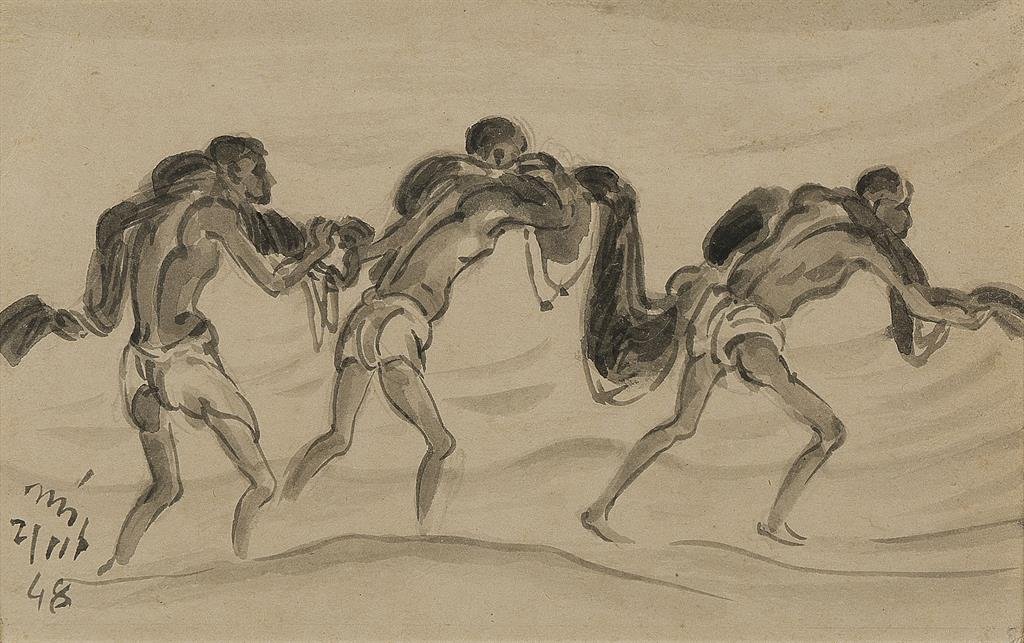

Japanese and East Asian art, particularly wash painting and printmaking, influenced his exploration of brushwork and the dynamics of line. The emphasis on brevity, swift gesture, and controlled tonality found in East Asian traditions helped shape Bose’s linear elegance and the subtle gradations of his color harmonies. He developed a visual rhetoric defined by graceful outlines, rhythmic movement, and a restrained, earthy palette, often privileging tonal variation and textural nuance over saturated chroma. The result was an image surface that felt simultaneously intimate and expansive, schematic and sensuous, capable of sustaining narrative scenes as well as distilled, emblematic forms.

In thematic terms, Bose’s art engages nature, rural Indian life, and mythological subjects, often treating them with sober lyricism rather than spectacle. Decorative motifs are incorporated with precision, not as mere embellishment but as structural elements that articulate the plane, guide visual attention, and pace the image’s internal rhythm. The balance he struck between narrative content and formal abstraction allowed him to render myth and everyday life in ways that resist both academic verisimilitude and purely ornamental revivalism. Flattened perspectives and simplified volumes are deployed thoughtfully, granting figures and landscapes a dignified presence aligned with the ethical core of his practice: to achieve modern form without severing ties to the cultural and environmental ground that nourished it.

This synthesis yielded an idiom that declined either extreme available at the time: uncritical imitation of European modernisms on the one hand, or nostalgic return to tradition on the other. Instead, Bose realized a dynamic middle path. His is a modernism neither derivative nor insular, one governed by proximity to materials and histories, and by a belief that aesthetic innovation could arise from careful study of indigenous forms catalyzed by responsible assimilation of external influences.

Key Artists & Works

A concise trajectory of Bose’s significance can be traced through several emblematic works. The linocut print Bapuji (1930), depicting Mahatma Gandhi during the Dandi March, is a landmark of modern Indian printmaking and a precise expression of how Bose condensed public ideals into spare, potent imagery. The image’s formal austerity—enabled by the linocut’s high-contrast economy—unfolds as a quietly forceful emblem aligned with the ethical temper of the freedom movement. Bapuji illustrates how a modern technique, adapted to Indian concerns, could carry a wide social resonance without resorting to melodrama.

The Haripura Posters (1938), created for an Indian National Congress session at the behest of Mahatma Gandhi, expanded this approach into a comprehensive visual program celebrating rural Indian life. Together they articulate a vision of modern Indian identity rooted in agrarian labor, craft, and community. Executed for public display, the posters mobilize simplified form, rhythmic design, and direct readability. They exemplify how Bose’s modernism operated across registers—from intimate prints to the performative scale of public art—while maintaining consistency of line, palette, and compositional intelligence.

Bose’s role in illustrating the manuscript of the Constitution of India stands as another pivotal contribution. In this project, the integration of pictorial elements within a foundational legal document demonstrates a rare alignment between art, civic purpose, and national consciousness. Rather than functioning as separate adornment, the imagery participates in the articulation of collective identity during the formative moment of statecraft. Taken together with his public commissions, this work clarifies how Bose’s visual language could inhabit solemn, institutional contexts without compromising aesthetic integrity.

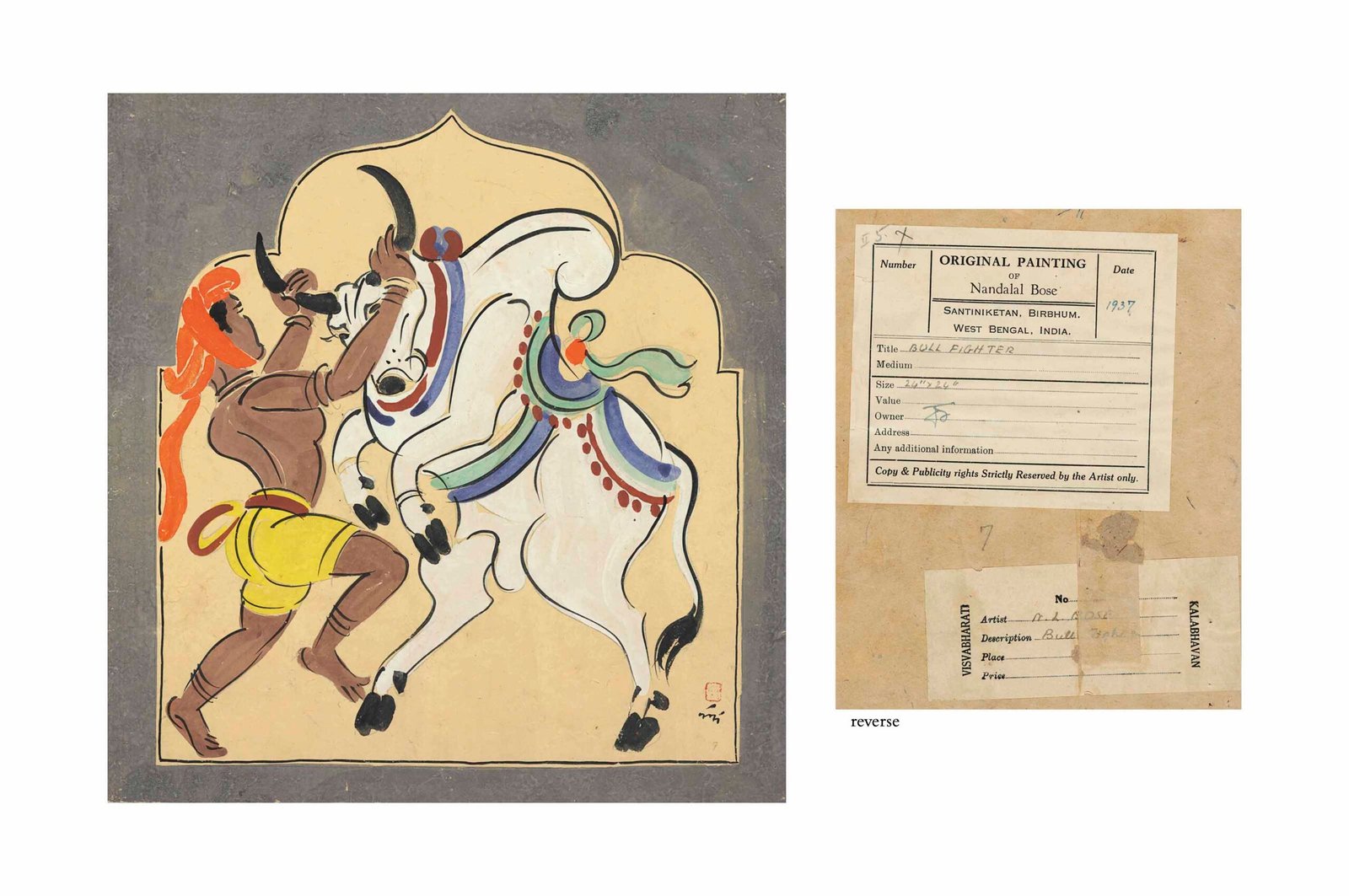

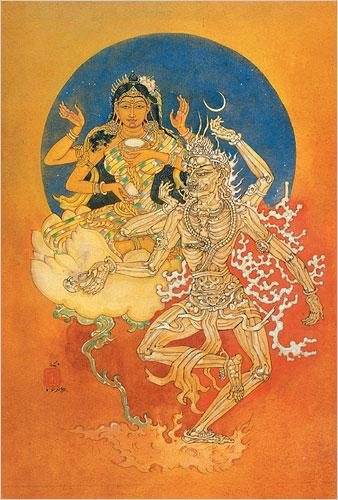

Alongside these, several paintings and series reveal the breadth of his interests and the consistency of his idiom. Works such as Sati, Shiva Drinking Poison, Birth of Chaitanya, Annapurna, Mother and Child, and Village Scene, as well as series on the Mahabharata, exemplify his sustained dialogue with mythology and everyday life. They are structured by an internal harmony of line and tone that quietly refocuses mythic narrative as a reservoir of ethical and aesthetic reflection. In each case, the modernity of approach is registered less in overt bravura than in disciplined design and a generative re-reading of inherited forms.

As a teacher and mentor, Bose’s impact radiated through the work of those he trained and influenced. Artists such as Benode Behari Mukherjee, Ramkinkar Baij, and K.G. Subramanyan went on to become leading voices in modern Indian art. The diversity of their practices—spanning mural, sculpture, painting, and design—attests to an educational ethos that encouraged rigorous study of Indian traditions coupled with inventive engagement with modern techniques. Their achievements, while distinct, bear the imprint of a Santiniketan pedagogy attentive to materials, environment, and the ethical dimensions of art-making, a framework to which Bose made a central contribution.

Materials & Techniques

Bose’s modernism is inseparable from his approach to materials. He favored tempera on handmade paper and watercolor using wash techniques, methods that reinforced his commitment to subtle gradations, quiet tonalities, and the primacy of line. Wash painting, informed by Japanese practice, enabled him to pursue flowing, controlled brushwork and a sophisticated handling of translucency. The aesthetic outcome—restrained yet resonant—sits at the heart of his redefinition of pictorial clarity for modern Indian contexts.

His engagement with printmaking, including linocuts and woodcuts, expanded his technical repertoire and public reach. By embracing matrix-based processes, Bose aligned the reproducibility, directness, and graphic force of these media with themes that demanded wide circulation. The linocut’s capacity for bold silhouettes and compressed narration found a natural partner in images like Bapuji, where economy of mark and clarity of contour became moral as much as formal virtues. Woodcut, with its grain and resistant surface, offered complementary possibilities for texture and structure.

Ink brushwork, sustained by a dialogue with East Asian exemplars, contributed further to the elegance of his line. Across formats, Bose often used natural dyes and pigments derived from earth and stones, aligning practice with indigenous methods. Such materials conferred specific chromatic and textural properties—muted earths, mineral resonances—that quietly ground the work in the subcontinent’s visual and environmental rhythms. The palette’s restraint encouraged attention to the interval between tones, the orchestration of line, and the ebb and flow of decorative motifs, giving form to a searching yet disciplined modern sensibility.

Beyond painting and prints, Bose was versatile across murals and illustration, adapting technique to scale and context without diluting stylistic consistency. In mural work, the emphasis on planar design and the interplay of figure and ground could be scaled up without sacrificing clarity. In illustration, his mark-making and compositional economy allowed text and image to cohere, as evidenced by his work on the Constitution manuscript. Across these media, technique was not an end in itself; it was a method for aligning means with message, material practice with ethical and cultural intention.

Influence & Legacy

Nandalal Bose’s legacy is anchored in his articulation of an indigenous modernism that joined tradition to contemporary concerns with unusual coherence. As principal of Kala Bhavana at Santiniketan from 1921 to 1951, he sustained an educational setting that prioritized cultural rootedness, experimentation, and cross-cultural exchange. There, the pedagogy refrained from reproducing European academic hierarchies or reducing Indian traditions to static canons. Instead, it fostered a working modernism centered on material inquiry, formal clarity, and historical consciousness—a model that would exert a lasting influence on Indian art education and practice.

His nationalist artworks contributed to the visual expression of the independence movement and the symbolic vocabulary of postcolonial nation-building. Projects such as the Haripura Posters and the Constitution manuscript made clear that modern art in India could operate in public, civic, and institutional spheres without forfeiting aesthetic discipline. His work for Indian National Congress sessions exemplified how carefully designed images could serve public communication while preserving formal subtlety. The commissioning of emblematic designs, including for national awards such as the Bharat Ratna and the Padma Shri, further indicates the degree to which his visual language resonated with the task of articulating new collective identities.

Institutionally and historiographically, Bose’s place is underscored by the continued study and exhibition of his work in major collections. Recognized as a national treasure, his art is preserved in institutions such as the National Gallery of Modern Art in Delhi and Bengaluru. Exhibitions at venues like the National Gallery of Modern Art and Chitrakoot Art Gallery, and presentations internationally including the Venice Biennale, have sustained and broadened the audience for his practice. Retrospectives and permanent collections have provided platforms for evaluating his contribution within the evolving narratives of Indian modern art, reaffirming his status as a pivotal figure whose work remains central to scholarship and public understanding.

Equally significant is the generative effect of his mentorship. Artists who passed through Santiniketan or were shaped by his teaching—among them Benode Behari Mukherjee, Ramkinkar Baij, and K.G. Subramanyan—pursued distinct modernisms that retained a commitment to materials, to an ethics of form, and to the interrogation of tradition in contemporary terms. Taken together, their achievements—varied across mediums and agendas—constitute a living legacy of Bose’s approach, which held that modern art should emerge from dialogue rather than rupture, from disciplined experiment rather than programmatic rejection.

Ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of Bose’s reach and methods. Archival work promises to clarify the breadth of his collaborations within the Bengal School and the Santiniketan circle, and to catalogue more comprehensively his oeuvre, including lesser-known pieces and their dispersal. Studies of reception across different regions and communities during his lifetime are poised to illuminate how his imagery traveled and how audiences interpreted it under varying historical conditions. Investigations into non-Indian influences beyond Japanese and East Asian practices may add nuance to the map of cultural exchange that shaped his style. Finally, closer attention to pedagogy—how curricula were designed, how studio practices were taught—will deepen our grasp of how Santiniketan fostered an environment uniquely conducive to Contextual Modernism.

Conclusion

Nandalal Bose’s art demonstrates how a modern tradition might be built: through attentive study of the past, disciplined experiment with materials, and an openness to cross-cultural dialogue in service of local concerns. Rooted in Indian artistic lineages yet informed by Japanese and East Asian techniques, his practice found a balance between narrative clarity and formal economy, between public purpose and aesthetic autonomy. His major works—such as the Bapuji linocut, the Haripura Posters, and the illustrated Constitution manuscript—exemplify an approach in which technique, image, and civic imagination coincide without theatricality. As principal of Kala Bhavana, he extended this vision to education, enabling a generation of artists to explore modern art as a contextual, ethically inflected endeavor.

In the broader story of Indian modernism, Bose marks a threshold. He neither capitulated to the assumptions of colonial aesthetics nor turned tradition into static heritage. Instead, he fashioned a modern idiom that takes the resources of Indian art seriously, translating them into a contemporary language responsive to the environments, histories, and aspirations of its time. His influence continues to shape how Indian modern art is taught, curated, and understood. As institutions, scholars, and artists reassess the interlaced histories of nationalism, pedagogy, and form, Bose’s work remains a touchstone—evidence that modernism in India has long been a dialogue, not a monologue, and that its strength lies in the thoughtful convergence of continuity and change.