The Architectural Grammar of the Nagara Style in North Indian Temple Architecture

Across the Indian subcontinent, Hindu temples articulate a distinctive architectural language that frames the encounter between the earthly and the divine. Conceived as sacred abodes of divinity, these structures translate cosmological ideas into space, mass, light, and movement. Within this broad tradition, regional styles emerged with their own grammars and textures—Nagara in North India, Dravida in the South, Vesara in the Deccan, and Kalinga in Odisha—each developing characteristic forms while sharing fundamental concepts such as the sanctum (garbhagriha), processional pathways, and ritual halls (mandapas). The Nagara style, the focus of this study, is best known for its curvilinear tower (shikhara) crowned by the ribbed disc (amalaka) and finial (kalasha), a vertical emphasis that signals ascent and transformation. Iconic examples demonstrating the richness of India’s temple traditions include the Lingaraj Temple in Bhubaneswar, the Brihadeshwara Temple in Thanjavur, the Kandariya Mahadev Temple in Khajuraho, and the Kailasa Temple at Ellora; considered collectively, they show the range of formal strategies Indian architects employed to build sacred centers, even as each region maintained a distinct grammar. Within the Nagara idiom, the plan is typically square or rectangular and may be articulated into a cruciform shape through projections (rathas); halls and passageways extend the space of worship while maintaining an axial clarity. Ornamentation is not mere embellishment but operates as an integral part of the architectural system, structuring the surfaces into self-similar bands and motifs that reinforce the temple’s symbolic function. This article outlines the historical evolution of the Nagara style, analyzes its core structural features and layout, examines its sculptural and iconographic program, and situates its cultural significance within the wider matrix of Indian sacred architecture, offering an evergreen overview oriented to both specialists and informed readers.

Historical Background

The architectural vocabulary of Hindu temples evolved over many centuries, drawing on ritual practices and spatial ideas that can be traced to early Vedic altars and cave shrines beginning around the 3rd century BCE. The Gupta period (4th–6th centuries CE) is widely regarded as a decisive experimental phase for structural stone temples, during which key typologies took shape, including Nirandhara (without an inner circumambulatory passage), Sandhara (with an internal circumambulatory passage), and Sarvatobhadra (open on all sides). These typologies clarified how sanctum, ambulatory, and mandapas could be combined to translate ritual requirements into durable architectural forms. In the post-Gupta periods, regional identities crystallized, producing the principal styles recognized today: Nagara in the north, Dravida in the south, and Vesara across the Deccan. Odisha’s Kalinga tradition developed from the 6th to the 16th centuries CE and reached maturity between the 11th and 13th centuries, demonstrating a sustained engagement with geometric evolution and repetitive patterns. Temple building continued vigorously through subsequent periods, including Vijayanagara and Nayaka times, with increasing monumentality and layered spatial complexity. Archaeological sites such as Deogarh, Bhubaneswar, Khajuraho, Ellora, and Pattadakal provide material evidence that complements textual traditions, reinforcing knowledge of temple proportions, plans, and construction methods. Inscriptions, including those like the 1235 A.D. record at the Amritesvara temple in Karnataka, document architectural styles and building processes, giving scholars insight into the terminology and practices of temple construction. Excavations at Harappan sites further reveal sophisticated urban planning and construction techniques that influenced later architectural developments. The textual corpus—Varahamihira’s Brhat Samhita, the Matsya, Agni, Garuda, and Visnudharmottara Puranas, alongside manuals such as the Samarangana Sutradhara and the Mayamata—supplies prescriptive and descriptive frameworks that inform interpretation of extant temples. Within this broader panorama, the Nagara style took shape as a coherent grammar, distinguished by its curvilinear tower and clear axial planning, while remaining responsive to regional materials, ritual patterns, and evolving iconographic programs.

Architecture & Layout

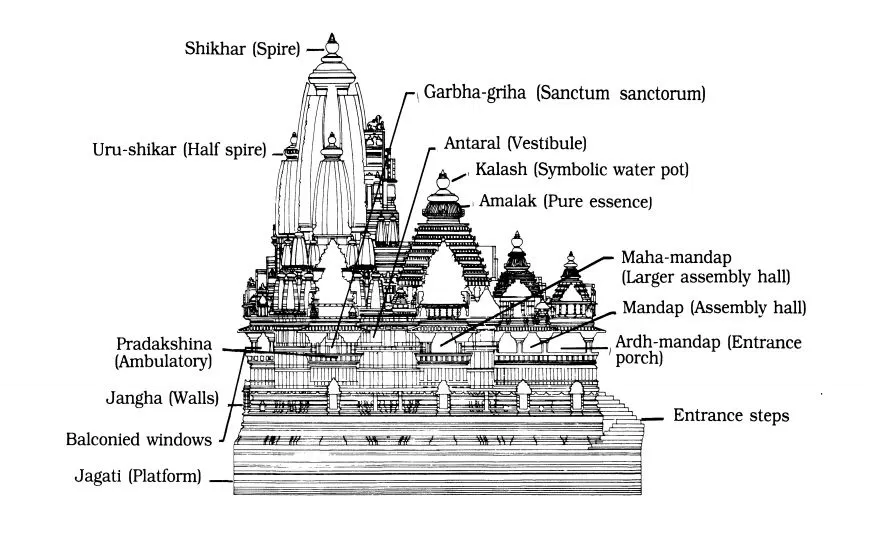

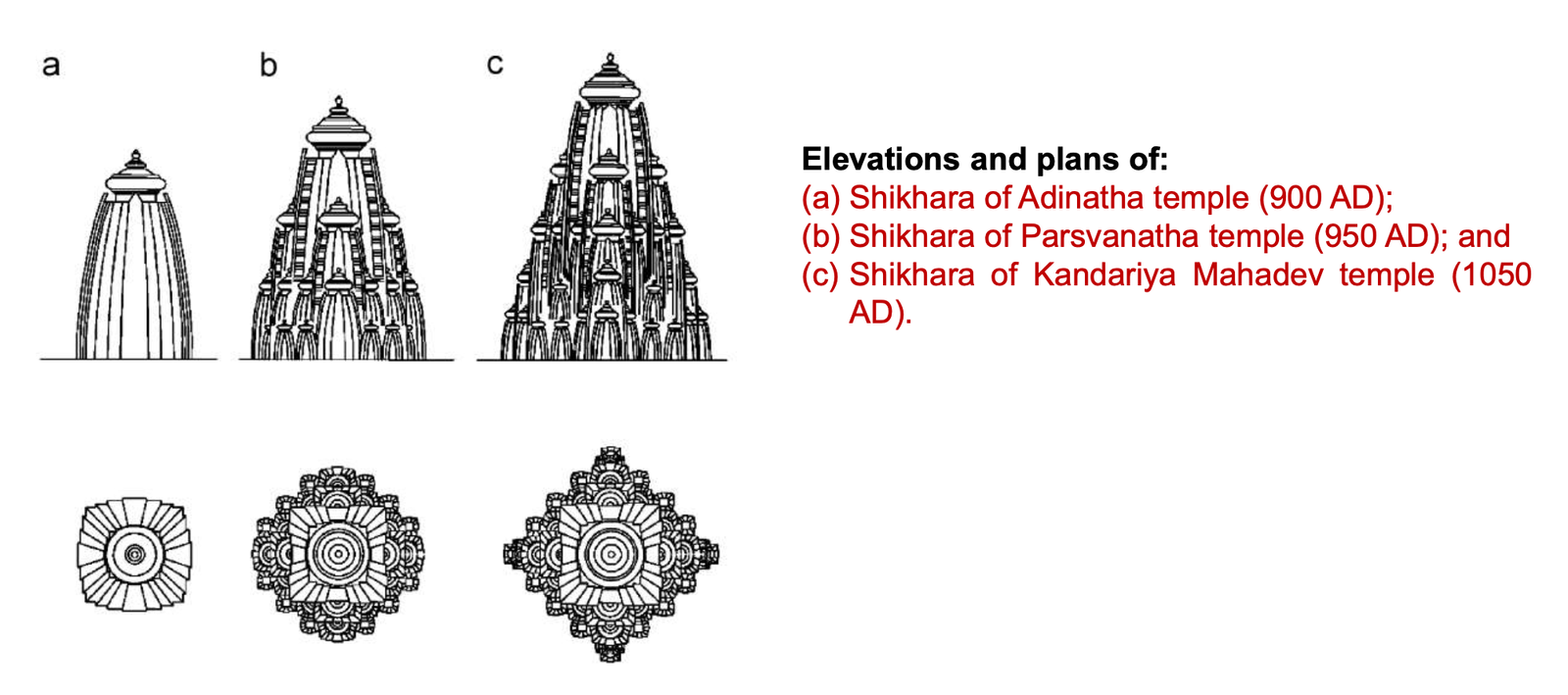

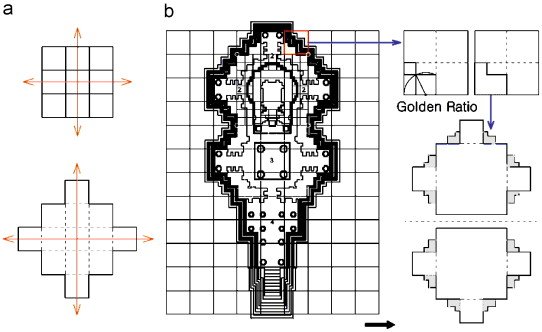

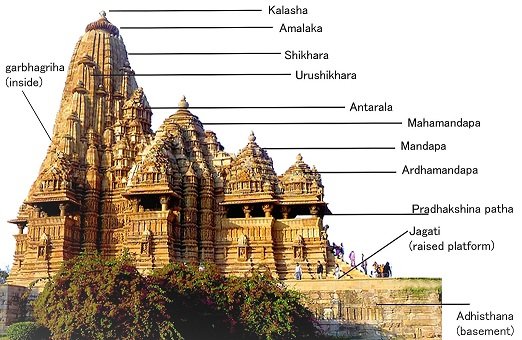

Nagara temple architecture is recognized by a lucid synthesis of plan, elevation, and ornament, unified by the curvilinear shikhara rising above the sanctum (garbhagriha). The foundational plan tends to be square or rectangular, often developed into a cruciform geometry through projecting offsets known as rathas, which modulate the exterior wall and enrich the rhythmic interplay of light and shadow. The sanctum anchors the composition, while ancillary spaces—mandapas (pillared halls), antaralas (vestibular links), and circumambulatory pathways (pradakshina paths)—extend and articulate the ritual journey. In this arrangement, key Gupta-derived typologies shape circulation: Nirandhara layouts emphasize inward focus without an inner ambulatory, while Sandhara and Sarvatobhadra types support circumambulation within more permeable envelopes. Gateway structures (toranas) frame entry points, and boundary enclosures (prakaras) delineate the sacred precinct, within which subsidiary shrines and ritual elements create a layered complex. Elevationally, Nagara grammar organizes the temple into recognizable bands: a base or platform (pitha), a moulded course (vedibandha), a principal wall zone (jangha), a cornice or transition (varandika), and the superstructure (shikhara) culminating in crowning elements. The hallmark shikhara is curvilinear, increasingly compressed as it ascends, and is crowned by an amalaka (ribbed disc) and a kalasha finial, an ensemble that reinforces vertical thrust and visual coherence. Within the Nagara family, subtypes refine this profile and the associated roof forms: Rekha-Prasada (Latina) denotes the archetypal curvilinear tower; Phamsana, analogous to pida-like stepped pyramidal roofs, is frequently associated with mandapas; Bhumija and Shikhari styles represent further compositional strategies within the same idiom. While design varies with context, Nagara temples commonly incorporate toranas and clearly defined processional routes, facilitating a progression from the public to the sacred. The total composition balances geometry and ornament, integrating repetitive motifs with the formal silhouette so that structure and decoration operate together. This disciplined grammar allows for significant variety, ensuring that even within uniformly recognizable features—garbhagriha, mandapa, pradakshina path, and shikhara—each temple can present a distinct spatial experience aligned with its ritual functions and local craftsmanship.

Sculpture, Inscriptions & Iconography

Nagara temples, like their counterparts elsewhere in India, are richly endowed with sculptural and ornamental programs that transform architectural surfaces into narrative and symbolic fields. Reliefs portray deities, mythological episodes, and cosmological motifs alongside vegetal scrolls and geometric patterns, generating a visual exegesis of sacred themes. Guardian figures (dvarapalas) and attendant beings such as ganas mark thresholds and key ritual zones, while other symbolic creatures, including yalis in broader Indian practice, contribute to a language of protection, vitality, and transformation. In the Nagara context, the sculpture often amplifies the vertical logic of the shikhara and the graded surfaces of projections (rathas), with bands and niches coordinated to architectural members. Sites such as Khajuraho are renowned for elaborated figural cycles, including erotically charged sculptures, that integrate human experience into a cosmic schema; here the ornamental density does not simply decorate but structurally organizes façades, distributing weight visually and reinforcing proportional rhythms. Ornamentation frequently demonstrates principles akin to fractal geometry, with self-similar patterns repeating across scales—from base mouldings to the culmination of the tower—achieving both unity and intricacy. The iconographic program aligns with Hindu cosmology and mythology, embedding doctrinal and ritual references within a system of images that supports the devotee’s cognitive and ritual engagement. Insights into this program’s formulation and execution are augmented by epigraphic and archaeological evidence. Inscriptions, such as those from the 13th century at temples like Amritesvara in Karnataka, record architectural styles and construction details, offering terminological anchors and historical snapshots that aid comparative analysis across regions. Excavated and standing complexes at Deogarh, Bhubaneswar, Khajuraho, Ellora, and Pattadakal supply datable material for correlating textual prescriptions with built forms, while textual authorities—from Varahamihira’s Brhat Samhita to manuals like the Samarangana Sutradhara and the Mayamata, and Puranic sources including the Matsya, Agni, Garuda, and Visnudharmottara—provide a theoretical scaffolding for interpreting layout, proportion, and image placement. Across this evidence, the Nagara idiom emerges as a disciplined yet adaptable framework in which sculpture, inscription, and iconography are integral to architectural meaning rather than applied embellishment.

Cultural Significance

In the Nagara style, as in Indian temple architecture more broadly, the temple functions as a microcosm of the universe and as an embodiment of the cosmic person (Purusha). The garbhagriha—the sanctum or “womb chamber”—houses the murti and represents the spiritual heart of the complex, an axis of presence from which the temple’s spatial and symbolic order radiates. The layout follows the Vastupurusha Mandala, a sacred geometric grid that aligns foundations, walls, and superstructures with cosmic principles, mapping the positions of deities onto spatial modules. This alignment informs not only plan geometry but also orientation, with entrances typically facing cardinal directions—often east or north—to harmonize ritual movement with solar and cosmic cycles. The temple’s architectural elements encapsulate metaphysical concepts: the base and rising wall strata suggest a movement from the terrestrial toward the celestial; the shikhara’s ascent culminates in crowning members that signify completion and consecration; and the concatenation of parts embodies the Pancha Bhootas, or elemental constituents of existence, as interpreted through stone. The ritual journey—from the open mandapa through the narrowing axis to the dark sanctum—enacts a passage from the manifold world to unity, mirrored by the temple’s compositional concentration around the sanctum. Yet the temple is also a lived institution. It serves as a center for ritual worship, festivals, education, and social gathering, integrating the arts—sculpture, music, and recitation—into communal life. In this sense, the Nagara grammar provides a legible framework within which local traditions, craft lineages, and regional iconographies operate. The coherence of plan and elevation ensures that liturgical practices, performative arts, and visual narratives are not discrete layers but mutually informing aspects of a designed sacred environment, allowing the temple to sustain both spiritual and cultural functions over extended historical durations.

Visiting / Access Information

Visitors to a Nagara temple encounter a spatial sequence carefully aligned to ritual use and cosmological orientation. Approaches are typically keyed to cardinal directions, with an emphasis on eastern or northern entry aligning movement with auspicious axes. Gateways, occasionally expressed as toranas, mark transitions from secular space into the sacred precinct, which may be enclosed by prakaras that define thresholds for ritual purification and assembly. Within the complex, mandapas provide covered areas for gathering, recitation, and music, and often mediate the shift from the more public outer zones to the progressively restricted sacred core. Circumambulatory paths (pradakshina) are integral to the visitor’s experience; where the layout is Sandhara or Sarvatobhadra, devotees can encircle the sanctum internally, while exterior paths enable broader participation in processional rites. Subsidiary shrines within the enclosure create a network of devotional points, supporting festivals and specific vow-rites. The architectural grammar of rathas and projections on the exterior walls produces visual cues for circumambulation, as mouldings, niches, and iconographic panels prompt attentive movement. While large Indian temple complexes may possess multiple entrances and elaborate monumental markers, Nagara emphasis remains on the sanctum’s shikhara as the primary visual beacon. In many traditions, consecration ceremonies (Pranapratistha) animate the deity’s presence within the sanctum, after which routine worship and seasonal observances structure the temple’s daily and annual rhythms. For the thoughtful visitor, understanding the basic grammar—entrance alignment, mandapa-to-sanctum progression, and the role of pradakshina—enhances appreciation of how architecture, movement, and ritual interlock to shape the sacred experience in the Nagara context.

Conclusion

The architectural grammar of the Nagara style distills centuries of experimentation and regional exchange into a coherent system that is at once formal, functional, and symbolic. Its square or rectangular plans, often articulated into cruciform configurations with rathas, organize a ritual journey through halls and passages toward the concentrated core of the garbhagriha. The curvilinear shikhara, crowned by the amalaka and kalasha, is more than a visual signature; it is the apex of a layered composition in which base, wall, cornice, and superstructure are integrated by proportion and ornament. Sculpture and iconography, coordinated with architectural members, transform surfaces into narrative fields and symbolic diagrams, while inscriptions, archaeological remains at sites such as Deogarh, Bhubaneswar, Khajuraho, Ellora, and Pattadakal, and textual sources including the Brhat Samhita, Puranic literature, and architectural manuals, collectively substantiate and clarify the Nagara idiom. Culturally, the style sustains the temple’s role as a microcosm aligned to the Vastupurusha Mandala, a place where cosmic order is rendered tangible and where community, ritual, and learning converge. At the same time, several research frontiers invite continued inquiry: the precise interpretation and practical application of certain architectural terms (for example, kaṭi and nirgama); the extent to which fractal-like patterning reflects conscious geometric planning versus emergent craft traditions; the correlation of textual prescriptions with measured data from less-studied regional manifestations; the evolution and regional variations of Vastupurusha Mandala types and their influence on design; and the relationship between ritual diagrams and construction drawings across periods and regions. Addressing these questions will deepen understanding of how the Nagara grammar mediated between scriptural ideals, artisanal technique, and living ritual. As an evergreen subject, the Nagara style continues to offer scholars, practitioners, and visitors a compelling lesson in how architecture can coherently unite cosmology, community, and craft into a durable and legible sacred form.