Konark Sun Temple: Architecture, Iconography, and Sacred Symbolism in Medieval India

The Konark Sun Temple, on the eastern coast of India in Odisha, is one of the most accomplished creations of medieval South Asian architecture. Situated in the town of Konark, about 65 kilometers from Bhubaneswar and 35 kilometers from Puri, the complex was conceived as a monumental chariot of the Sun God Surya. Its design fuses architectural innovation with an intricate iconographic program, employing the chariot motif with twenty-four carved stone wheels and seven powerful horses to embody solar movement and cyclical time. Although the towering sanctum has not survived, the remaining structures—particularly the great assembly hall or Jagamohana—continue to express the ambition of a royal project built in the thirteenth century under the Eastern Ganga dynasty. Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1984, the temple remains a touchstone for the Kalinga school of the Nagara tradition, a locus of Odisha’s cultural identity, and a vital case study for scholars exploring the intersections of architecture, cosmology, and royal ideology.

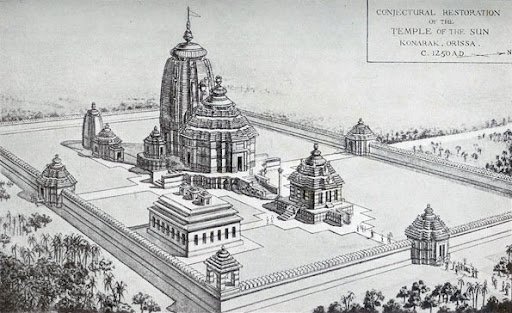

Set originally close to the Bay of Bengal and now approximately three kilometers inland due to geographical change, the temple compound once comprised the towering Rekha Deula (sanctum), the Jagamohana, the open Natamandapa (dance pavilion), and a suite of subsidiary shrines. Even in its partial state, the site attests to an extraordinary command of stone, structural geometry, and narrative sculpture. Its celebrated east–west alignment, archaeoastronomically tested sundial features, and wide-ranging sculptural repertoire illustrate an art and architecture designed to function as ritual space, timekeeper, and royal statement all at once. Konark’s enduring appeal lies as much in its technical sophistication as in the layered meanings projected through its forms and images.

Historical Background

The Konark Sun Temple was constructed in the mid-thirteenth century CE, approximately between 1238 and 1255, under King Narasimhadeva I of the Eastern Ganga dynasty. Built amid a period of military assertion and cultural efflorescence, the temple operated as both a monumental act of devotion to Surya and a celebration of the king’s victories. Contemporary records state that the project was realized through the labor and artistry of around 1,200 artisans over roughly twelve years, a scale befitting the ambition of a court determined to produce a definitive architectural statement in stone.

Konark is often situated within what scholars identify as the culmination of the third phase of Kalinga temple architecture. This period consolidated earlier regional developments into a sophisticated Nagara idiom marked by strong vertical accents, a well-ordered square-based plan, and an exceptionally rich sculptural mantle. The architectural language at Konark takes this regional idiom to a grand scale, situating it within a solar cosmology that frames the king’s authority as aligned with cosmic order.

Despite its initial prominence, the temple appears to have been used actively for worship for a relatively short span. Over centuries, the complex suffered damage and decline due to a combination of factors. Accounts refer to the destruction associated with invasions—most notably those attributed to Kalapahad in the sixteenth century—as well as to structural vulnerabilities and natural forces. The precise sequence and causes of the main sanctum’s collapse remain the subject of research, with multiple theories under consideration. Changes in the local coastline and evidence of coastal subsidence have also influenced the temple’s condition. In modern times, the Archaeological Survey of India has periodically documented preservation issues, while international recognition of the site as a UNESCO World Heritage property in 1984 has underscored its global significance and the imperative of conservation.

Architecture & Layout

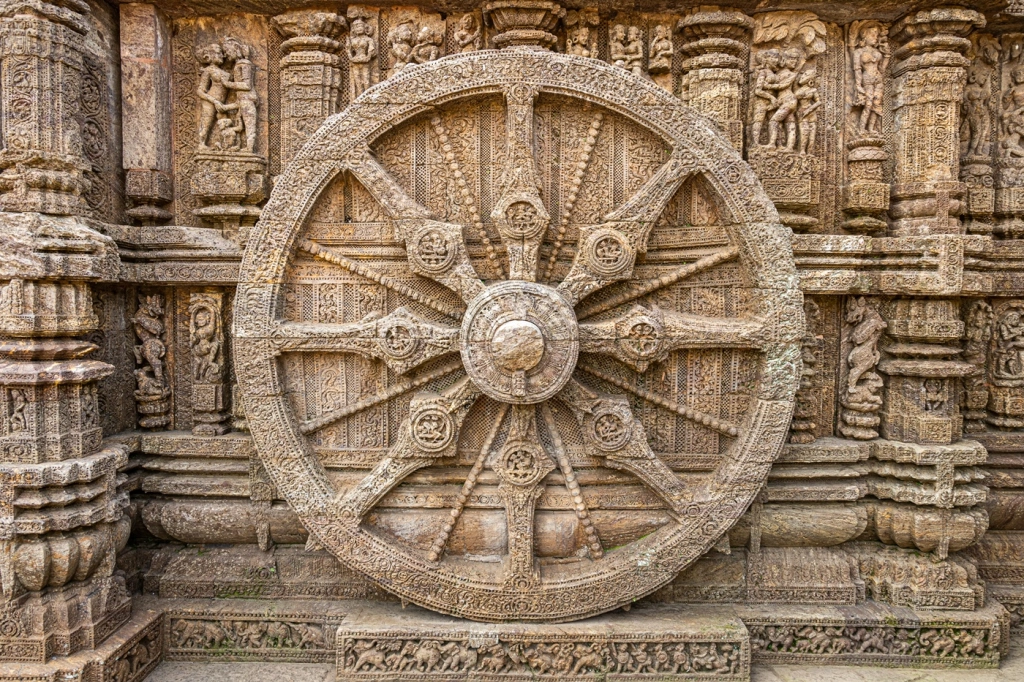

Konark is a representative pinnacle of the Kalinga school of Nagara architecture. The complex follows a square plan and dramatizes verticality through its elevations and projections, orchestrating light and shadow across profiled surfaces. Its most striking conceptual innovation is the transformation of the temple itself into Surya’s chariot: twenty-four massive stone wheels and a team of seven horses animate the platform and walls, binding structure, symbol, and ritual into a single architectural narrative. The wheels, measuring approximately 10 to 12 feet in diameter, are designed not as mere ornament but as functional sundials, their spokes casting calculable shadows to indicate time. This union of cosmic metaphor and practical timekeeping situates the building as a mediator of celestial rhythms.

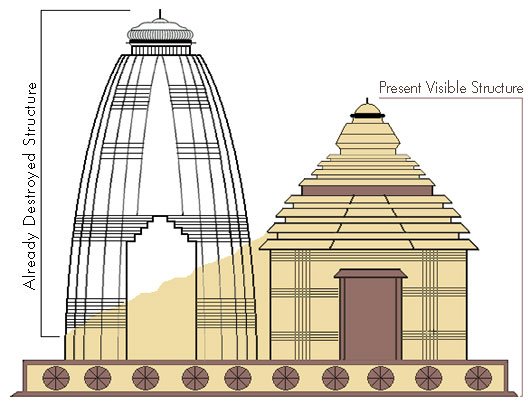

The temple’s plan exhibits the pancharatha style, with five vertical projections articulated on each facade. These projections, or rathas, generate faceted surfaces that register changing daylight, heightening the sculptural effect and contributing to a sense of mass and motion. In its original state, the sanctum or Rekha Deula rose in a soaring tower, about 70 meters high, that would have dominated the coastal horizon. Although the main tower has collapsed, its intended relationship with the surviving Jagamohana remains legible in the plan and elevations: a dynamic of axial procession and volumetric contrast.

The Jagamohana, or assembly hall, is the best-preserved major structure at Konark. Characterized by a terraced, pyramidal superstructure, it displays profuse exterior ornament, including narrative friezes, deities, and courtly scenes. This hall bridges symbolic and social functions: as an orchestration of sacred imagery and as a space of congregational presence. The Natamandapa, or dancing hall, once opened into the ritual axis with a forest of pillars supporting a now-lost roof. The profusion of carvings on its piers—dancers, musicians, and attendant figures—testifies to the role of performance in the ritual life of the temple, articulating a synesthetic environment where sound, movement, and sculpture intersected.

Konark’s alignment along an east–west axis is integral to its conception. The orientation was intended to capture the first rays of the rising sun, channeling light into the sanctum and ensuring that diurnal cycles were not only symbolized but also physically inscribed into the space. Modern archaeoastronomical studies have affirmed the careful planning behind both the orientation and the sundial function of the wheels, underscoring the architects’ command of celestial observation and its translation into architecture.

The material palette and construction practices reflect regional expertise. Builders employed laterite, chlorite, and khondalite stones, working them into finely carved blocks and assembling the fabric with iron cramps and dowels. This combination facilitated both monumental scale and intricate detailing. Among the local legends that speak to the temple’s marvels is one that the great superstructure was once stabilized by powerful magnets or lodestones. While this story endures in regional memory, definitive archaeological evidence is lacking, and it remains part of the temple’s lore rather than its documented engineering history. Narratives also recall the later removal of such lodestones during the colonial period, but here again, firm evidence has not been established.

Beyond the primary triad of sanctum, Jagamohana, and Natamandapa, the complex included subsidiary shrines and functional structures. Of particular note are the Mayadevi Temple and the Vaishnava Temple, which integrate the broader sacred landscape of the site. A bhogamandapa, or refectory, formed part of the ritual economy, though the precise functions and sequences of use remain areas for further study. The Aruna Stambha, a monolithic pillar originally part of the Konark ensemble, now stands at the Jagannath Temple in Puri, a relocation that visually and symbolically connects two major cultic centers of Odisha. Collectively, these components suggest a carefully planned ceremonial topography, organized around solar symbolism, processional movement, and royal presence.

Sculpture, Inscriptions & Iconography

Almost every exterior surface at Konark is animated by sculpture. The carvings span deities, celestial beings, dancers, musicians, animals, composite creatures, and narrative scenes that evoke courtly life, festivity, and the realities of thirteenth-century society, including depictions of war, military processions, and hunting. This crowded iconographic field establishes the temple as a microcosm in stone, presenting a world ordered and energized by the sun’s journey.

The chariot metaphor is worked out with notable rigor. The seven horses harnessed to the chariot are widely understood to signify the seven days of the week and the seven colors of sunlight, thus linking calendrical time to spectral phenomena. The twenty-four wheels evoke the hours of the day or the months of the year, making the walls themselves instruments of temporal reckoning. Within this frame, the spokes of the wheels have been interpreted to represent stages of life; one influential reading associates eight spokes with phases in a woman’s life, embedding human biography into the cosmic clock. Such convergences of mythic, astronomical, and anthropological symbolism exemplify the sophistication of the temple’s visual program.

Erotic sculptures, or mithunas, run in rhythmic bands along the plinths and walls. Far from being incidental decoration, these images articulate themes of fertility, prosperity, and the celebration of embodied life. They have been associated by scholars with tantric strands of practice and with the political idiom of royal patronage that sought to depict auspiciousness and plenitude. At Konark, their placement within a larger cycle of imagery suggests a system in which sexual union is understood within the generative cycles that the sun sustains, balancing sacred cosmology with human experience.

Power and moral commentary are expressed through allegory. The gajasimha motif at the entrance—lions overpowering elephants—has been read as a visual aphorism on the destructive effects of pride and greed. These images would have functioned as ethical signposts for those entering the temple precinct, situating the devotee or visitor in a landscape that is both didactic and celebratory. Elsewhere, the abundance of musicians and dancers carved into the Natamandapa’s pillars underscores the integration of performance with worship and royal ceremony, suggesting an environment in which image, sound, and movement amplified one another in praise of Surya and the cosmic order he represents.

Epigraphic and archaeological records help anchor the temple within its historical matrix. Copper plate inscriptions attribute the foundation to King Narasimhadeva I, and refer to the vow of his predecessor, Anangabhima III, establishing a dynastic continuity for the Surya cult and its monumental realization at Konark. Surveys of the site have revealed buried foundations and evidence of coastal subsidence that affected structural stability. Conservation reports by the Archaeological Survey of India have documented ongoing preservation challenges, a literature that continues to expand as new methods and materials are brought to bear on long-term stabilization.

The interpretive record is complemented by the careful relocation of many sculptures and panels to institutional collections for preservation. Numerous pieces are now housed at the Konark Museum and at the National Museum in New Delhi, where their carving, iconography, and inscriptions can be studied under controlled conditions. Likewise, the Aruna Stambha—once an integral axial element at Konark—stands today at the Jagannath Temple in Puri, a re-siting that reflects both historical shifts and a continuing dialogue among the region’s foremost sacred centers. Together, the inscriptions, museum holdings, and archaeological documentation provide a framework through which the temple’s original scope, later history, and current conservation can be more fully understood.

Cultural Significance

Konark’s dedication to Surya is distinctive within the panorama of Indian temple traditions, where solar worship occupies a comparatively specialized domain. The temple exteriorizes solar cosmology: the chariot, wheels, and horses make tangible the sun’s motion and the cyclicality of time. In this sense, the entire complex operates as a cosmographic diagram, translating celestial mechanics into architecture, sculpture, and ritual pathway. By aligning royal patronage with solar sovereignty, the temple functioned as a monumental proclamation of the Eastern Ganga king’s role as guarantor of cosmic order and terrestrial stability.

Within Odisha, Konark resonates as a central emblem of cultural identity. It forms the third vertex of the region’s “Golden Triangle” of sacred sites, alongside Puri and Bhubaneswar, and its images and motifs have influenced regional art, dance, literature, and state symbolism. The erotic bands are read as auspicious auguries for fertility and prosperity, reflecting the intersection of Brahmanical and tantric currents in medieval religious life. In contemporary cultural practice, the annual Konark Dance Festival brings classical Indian dance to the temple’s precincts, sustaining the historical association between performance and sacred space and providing a platform where heritage is not only exhibited but also re-enacted.

Visiting / Access Information

Konark is a prominent destination for both cultural tourism and pilgrimage. The temple complex is generally open daily from early morning to evening, with entry fees applicable and concessions available for Indian citizens and children. Certified guides can be engaged on-site, offering informed interpretations of the architecture, iconography, and historical context that enrich a visit. Basic visitor amenities, including restrooms, drinking water, and seating areas, are available near the complex.

Photography is permitted within the site, while drone operations require prior authorization. For deeper orientation, visitors may explore the Indian Oil Foundation Museum, also known as the Arka Kshetra Interpretation Centre, and the ASI Archaeological Museum, both of which present curated narratives and conserved sculptures from the temple. The nearby Chandrabhaga Beach and the Chaitanya Stone Carving Village complement a visit, and the Jagannath Temple at Puri offers a significant regional counterpoint in ritual scale and historical continuity.

Konark is accessible by air via Bhubaneswar, the nearest major airport. Rail travelers can arrive at Puri or Bhubaneswar stations and continue to the site by road, where local transport options are readily available. The cooler months from October to February are generally recommended for travel, providing more temperate conditions for exploring the open-air complex and its surrounding coastal landscape.

Conclusion

The Konark Sun Temple stands as a masterwork of Kalinga architecture and medieval Indian art. Its chariot plan; its east–west alignment and solar timekeeping features; its pancharatha articulation; and its integrated sculptural program combine to produce a monument in which architecture, astronomy, and royal theology converge. The record of copper plate inscriptions anchors the temple in the Eastern Ganga dynasty’s patronage, while the site’s later history—marked by partial collapse and ongoing conservation—underscores the complex interplays of material, environment, and human action that shape monumental legacies over time.

Konark’s continued resonance lies in its capacity to embody and communicate layered meanings. The twenty-four wheels and seven horses, the erotic friezes and moral allegories, the depictions of courtly and martial life, and the very presence of the Jagamohana and Natamandapa within a ritual topography evolve into a coherent statement about time, power, and cosmic order. As scholarship advances and conservation efforts respond to coastal and material dynamics, the temple’s significance remains evergreen—an enduring source for the study of sacred architecture and iconography, and a living symbol within Odisha’s cultural landscape.